Thread

Want to understand the intricacies of China’s economy? Read Arthur Kroeber’s China’s Economy: What You Need to Know (2016).

Kroeber sets the expectation up front--China’s economy is like a jigsaw puzzle w/ pieces that constantly change. It takes humility & grit to grasp. 1/52

Kroeber sets the expectation up front--China’s economy is like a jigsaw puzzle w/ pieces that constantly change. It takes humility & grit to grasp. 1/52

**Only after wrapping the 2016 version, did I realize there’s a newer edition of the book with updated # s and insights up to 2020. I am reading the new edition and plan to follow up with another review. 2/52

2016 Kroeber offers a robust thesis on why China’s political economy has persisted. China had bad and good examples to emulate. It learned from failed communist states and from EAsian dev neighbors (land to tiller ag reforms, export-oriented manu,& financial repression). 3/52

However, some conditions were unique to China. I.e. 1979 China had almost zero legal/regulatory systems as a legacy of the failed social & econ policies 50s through 70s. It was a legal & regulatory vacuum ripe for mobilization. 4/52

Though the book covers topics ranging from the rural economy, urbanization and infrastructure, enterprises, fiscal system, financial system, energy and climate change, labor market and demographics, and the emerging consumer market, there are some shared through lines. 5/52

(1) MOBILIZATION vs EFFICIENCY. China’s massive economic size and its backward economic standing (esp. after the ravages of the failed 50s through 70s policies) required a MOBILIZATION-first (EFFICIENCY-second) approach. 6/52

Resources and people needed to be marshaled first, often at the cost of efficiency. Going forward, China needs to become a high EFFICIENCY economy, with major productivity upgrades across all economic activities. 7/52

(2) CENTER vs LOCAL. China’s sheer size (and consequent many province level jurisdictions) gives provincial leadership leeway to run with localized adaptations of centrally-dictated policies. It gives room for policy innovation, but also leads to political tension. 8/52

(3) SOCIAL & POLITICAL CONTROL vs ECONOMIC GROWTH. The former trumps the latter. In urban policy, the persistence of the hukou and restrictions of migration into the largest cities demonstrates the party’s preference of control over growth. This preference hurts growth. 9/52

Now, making a laundry list of items that was notable to me. Not exhaustive -- 10/52

#1. PRC leadership seems incapable of crafting long-term policy that benefits both urban and rural constituents. When push came to shove, the rural Chinese got the worse deal. E.g. land use disparities (36-37) -- 11/52

Property ownership disparity underlines China’s urban-rural inequality. Urban ppl can buy and sell properties, especially after SOE housing unit reforms in the 90s. Rural ppl cannot sell land & only have contract rights (34). 12/52

#2. Interesting tidbit that Hu and Wen were instrumental in establishing a basic social safety net in both urban and rural areas, though typically urban elites had blamed a “wasted decade” in early 2000s (p. 34). 13/52

#3. At one point in the book, Kroeber usefully compares China’s SOEs w/ Japan’s Keiretsus & SKorea’s Chaebols. Kereitsu & Chaebols differ= Ks have a main bank at the center, Cs are prohibited by law to own banks. Both however have cross shareholding structures. 14/52

#4. China’s SOEs are different from both because: 1) no banks ownrship, or else might not be responsive to the state; 2) communist, so private enterprise not an attractive model, 3) state preferred firms to be in some industries instead of becoming sprawling empires (93). 15/52

#5. On the balance of power between state enterprise & the private sector…State enterprise is likely to decline over time in share of economic activity, though SOEs continue to wield greater political power and resources. 16/52

The gov’t in 2013 was not willing to let go of state ownership, but proposed mixed ownerships that had, well, mixed results (forgive me the joke was right there..109). 17/52

For central SOEs, mixed ownership is not an option. PRC mirrored Singapore’s model of shifting SASAC to asset management companies in charge of strategic industries, like Singapore’s Temasek (110). 18/52

#6. When dealing with the center v local dynamic, Kroeber sees it in two ways. Quantitatively, China may seem more decentralized, given the high % of fiscal expenditure handled by local govts (111-112). 19/52

#7. But qualitatively, China seems more centralized, as the organization department controls the assignment of its officials and checks local accumulated power. Moreover, though local govts collect revenue, central govt makes important policies in areas of taxation. 20/52

Kroeber implores the reader to embrace the noise and resist black-and-white framing. Instead, he posits both centralization and decentralization are apt and have explanatory power depending on the dynamic one’s analyzing. 21/52

E.g., China often experiments with policy in specially designated zones. Decentralized? Yes. But also, generally these zones have received blessing from the center. It’s possible to say China’s political economy is both decentralized & centralized (113). 22/52

Kroeber also discusses how locality is influential in dealing with issues of excess capacity and the proliferation of small players in industry (e.g. 120+ automakers in China). 23/52

#8. Onto the fiscal horizon -- Local government fiscal problem stems from a policy innovation in the 2000s: raising funds through land local govt owned. 24/52

Govts do so by transferring land assets to local govt financing vehicles. These vehicles would use land as collateral, and land sales proceeds would go to repayment of loans. Most of the finance was supplied by CDB. 25/52

Overtime, this got out of control as land was valued too highly, less conservative lenders joined the game and sometimes did not ask for collateral. Incurred massive liabilities. 26/52

The potential solution--transfer programs to localities--suffered from lack of standardization (121) which makes transfers costly and difficult. Without a solution in sight, how much should China worry about its local govt debt issue? 27/52

Kroeber noted that China’s gov debt is 54% of GDP around time of writing, which isn’t as high as OECD countries (>70%). The fiscal issue can be managed, but only if leadership solves the center vs local conundrum (part of Xi’s 2014 fiscal reform package, 120). 28/52

Moreover, there’s little incentive for local govt to tighten up fiscal practices given local govt bonds are not allowed to default. Rates are close to parity with central govt bonds (125). 29/52

#9. China’s level of debt itself is not worrisome, leverage (debt-to-gdp) of 230% is not as high as US and Japan. Fast rising debt however is an issue, but without the a trigger event, Kroeber argues a financial crisis is not imminent. 30/52

A trigger event where China is unable to pay back borrowers is unlikely, which often leads to a falling currency. Given its massive forex reserves, China can defend speculative attacks (135). 31/52

#10. Financial stability in China is at stake because debt’s growth rate may outpace economic growth. To tamp down debt growth, China has to tamp down credit. But that may slow down economic growth. A not so virtuous cycle (138). 32/52

#11. China did not devalue its currency after the Asian Financial Crisis. It actually tightened its peg to the USD. Kroeber cited two other reasons why China’s exports got more competitive: 33/52

1) Workers more productive, and 2) USD weakened, which made RMB cheaper against other currencies which made Chinese exports appealing (143). 34/52

#12. A crisis a decade later, the Great Financial Crisis in 07/08 hit China differently. While China’s finance system (closed) was not hit, its trade flows took some punches as trade finance activity dipped, because most letters of credits were denominated in dollars (146). 35/52

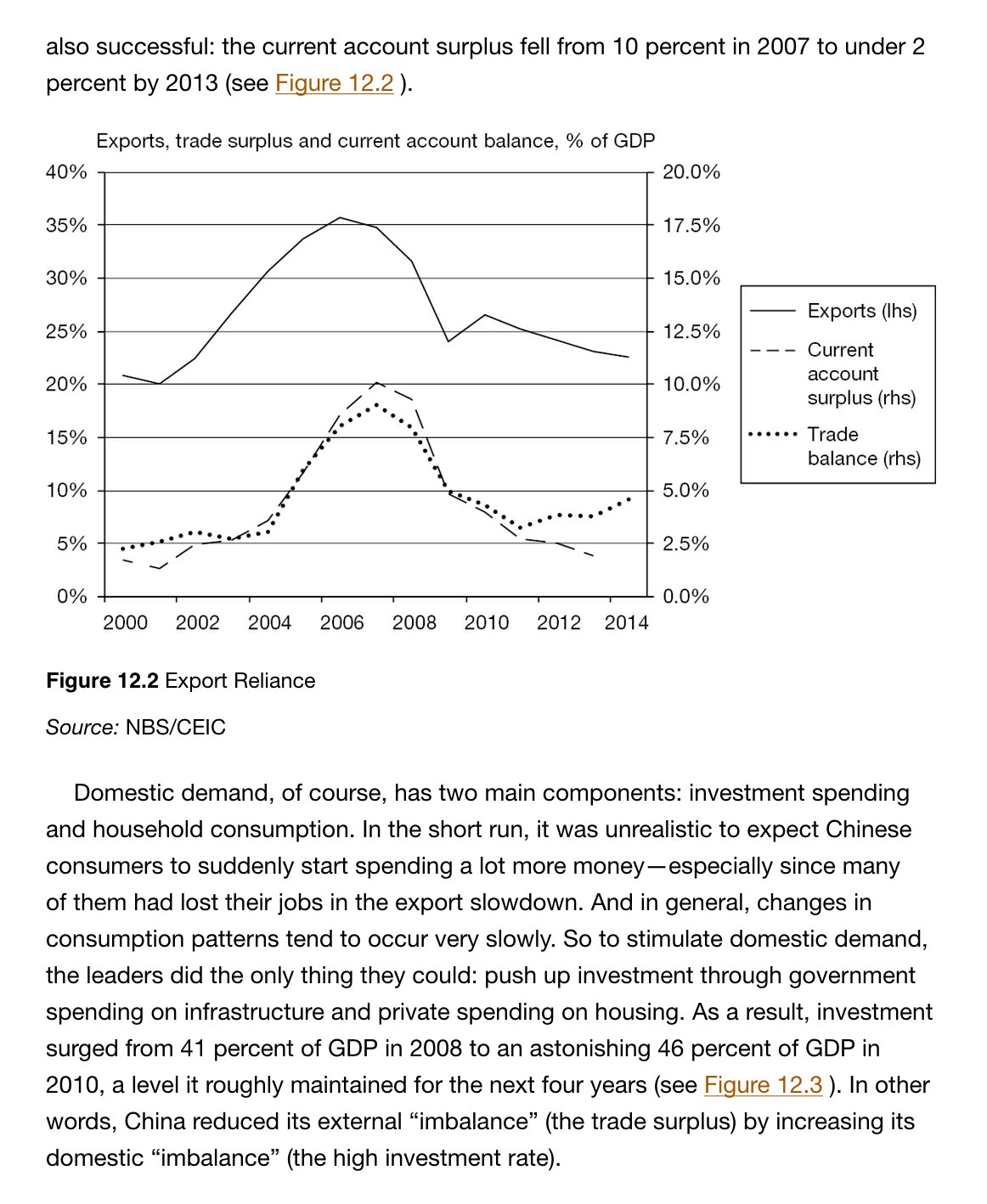

‘08 crisis revealed to Chn policymakers that PRC’s export-oriented model is vulnerable. It shifted reliance to domestic demand over exports for growth. Domestic demand can’t be consumption driven overnight, so PRC up’d its investment (217) 36/52

#13. The consumer economy chapter has a great reminder that China’s middle class is not the kind of middle class in the US context. It is neither a majority of Chinese society, nor is it an vocal advocate for political change. 37/52

#14. Fiscal reform introduced in 2014 were to be completed in 2016. One way to measure the strength of China’s political economy would be the evaluate how effective its proposed fiscal reforms panned out. 38/52

#15. Prescient of future winds in geopolitical tussles, Kroeber observed that economic size and might is not the primary ingredient in int’l influence, but rather technological capacity & political positioning (236) 39/52

And one of the biggest impediments (p. 256) is vested interests that inevitably come in the way, while intermingling with political power -- 41/52

Kroeber’s dissection of China’s economy is backed by data. The book often starts with the conventional wisdom then contrasts w/ data that supports an alternative thesis. Regardless of whether you agree w/ his assertions, it makes for engaging reading. 42/52

Since the book was published in 2016, and that some of the data dates back to 2013/14, the trends prescribed in this book are potentially a decade out of date. Nevertheless, the insights are still instructive. 43/52

There are a few ways to read this book. One way is to refer to each of the chapters for specific subject area insights. I opted for a full cover to cover, as I enjoyed the way the book keeps one on one’s toes re: challenging mainstream theses and offering alt ones. 44/52

This time capsule of a book, its hope “there is plenty of room in the world for both US & Chinese systems, so long as people on both sides can agree that this peaceful coexistence is a goal worth striving for,” seems strained if not entirely absent from the event horizon. 45/52

I’m excited to dive into the new edition (2020), as Kroeber takes inventory of China’s changing geopolitical position due to the CCP’s more activist foreign policy and the souring and hardening of US-China relations. 46/52

The 3 through lines in the 2016 edition--Mobilization vs Efficiency, Center vs. Local, and Social & Political Control vs. Economic Growth--would likely remain in the 2020 edition. However, the data and political and economic actors inside of China may look different. 47/52

The book also gives further reading at the end. It is an fantastic survey book for the layman, but also a great book for seasoned researchers who want to dive deeper into particular aspects of the Chinese economy. 48/52

Interestingly, Kroeber said scholarly study of the Chinese consumer economy “is a thing of the future.” 49/52

Besides proprietary research done by Gavekal and other firms and select WB reports, there is a dearth of analysis out there. Would be keen to see if this chapter gets a significant update in the new edition. 50/52

So, tl:dr -- Arthur Kroeber’s China’s Economy (2016) is worth the read. It gets you questioning established wisdom, and is thoroughly researched and skillfully presented. 51/52

Each section has questions as headers, like “How much of infrastructure is useful vs wasteful” & “How did China liberalize its interest rates.” He then answers them in powerfully succinct language. This is a tour de force that needs to be read & re-read. 52/52 -END-

Mentions

See All

Jordan Schneider @jordanschnyc

·

Jan 20, 2023

great thread!