Thread by Jonathon P Sine

Thread

“The Rise and Fall of Imperial China” by Yuhua Wang is a grand feat of a book. It covers an immense amount of history, undertakes extensive empirical work, and develops a powerful explanatory theory of state development..

But I have a fairly critical review of parts 🧵

But I have a fairly critical review of parts 🧵

The book is one in the tradition of “big history” books, striving to leverage history so as to develop a comprehensive theory that makes sense of a big chunk of the world. In this case how state's develop.

The primary thesis of the book is this: the rise and fall of not just imperial China, but the cause of state development broadly, is to be found in the characteristics of elite social networks and their relationship to the state.

A coherent network of national elites will be in favor of strengthening the state. A dispersed and highly localized elite social network, on the other hand, would rather hollow out the state—and perhaps disembowel it entirely.

Across China's dynastic history, emperors have faced what the book terms the “sovereign’s dilemma.” The dilemma is this: a coherent network of national elites allow the sovereign to strengthen the state, but that same elite network facilitates threats to his rule & even his life.

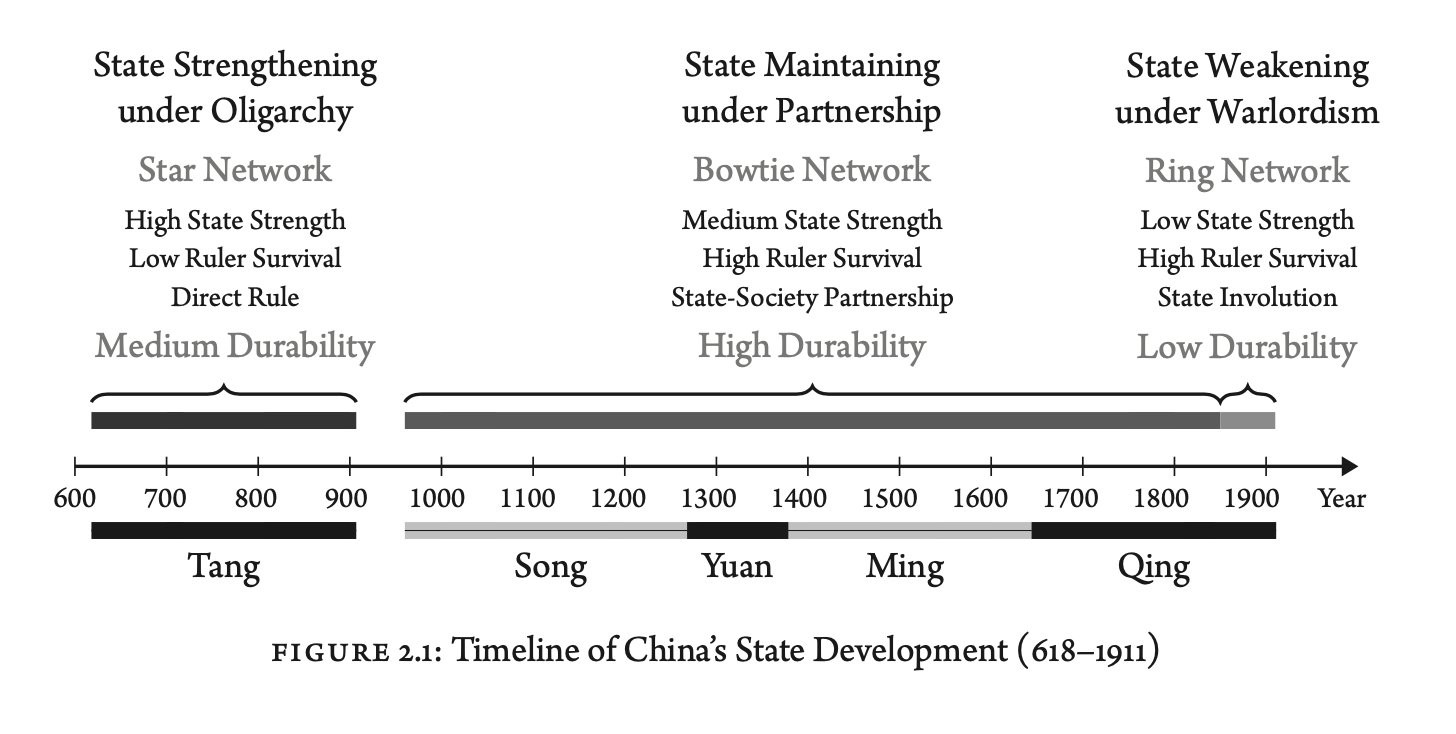

The book makes the case that China’s imperial history can be divided into three state-elite network typologies:

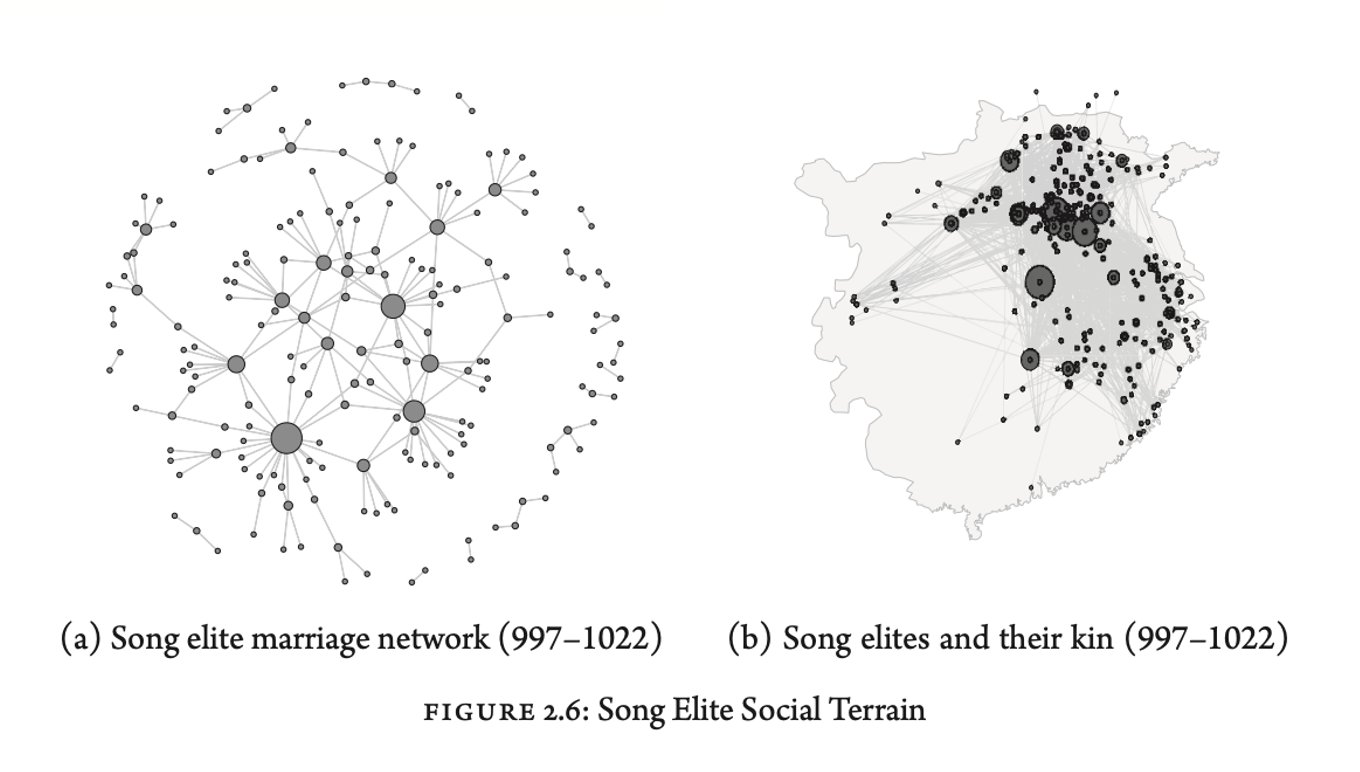

a star shaped network during the Tang dynasty at the twilight of China’s early dynastic period (600-900 AD) -- this networks exists when the elite are interconnected more nationally than locally, and strongly enmeshed into the central state governing apparatus:

a bow-tie shaped network for most of China’s later dynastic period beginning with the Song, moving into Ming & Qing (960-1800 AD) -- this network exists when elite are fragmented and more localized, but are still enmeshed with the central state governing apparatus:

and a ring shaped network in the latter part of the Qing (1850-1911) -- this network exists when elite networks are fragmented and localized and the elites are not enmeshed within a central state governing apparatus:

One of the core arguments the book puts forward is that China's sovereigns pursued strategies over time that weakened the state in favor of their own personal survival.

I'll take issue with this central argument below..

I'll take issue with this central argument below..

But first, to highlight the best part by far of this great book: the richness of the data and the empirical research that went into this project. Each and every substantive chapter is backed up with detailed empirical data painstakingly compiled..so fun to see all of it.

The empirical data are used to substantiate both general narratives put forth by earlier scholars, as well as the author's own claims...

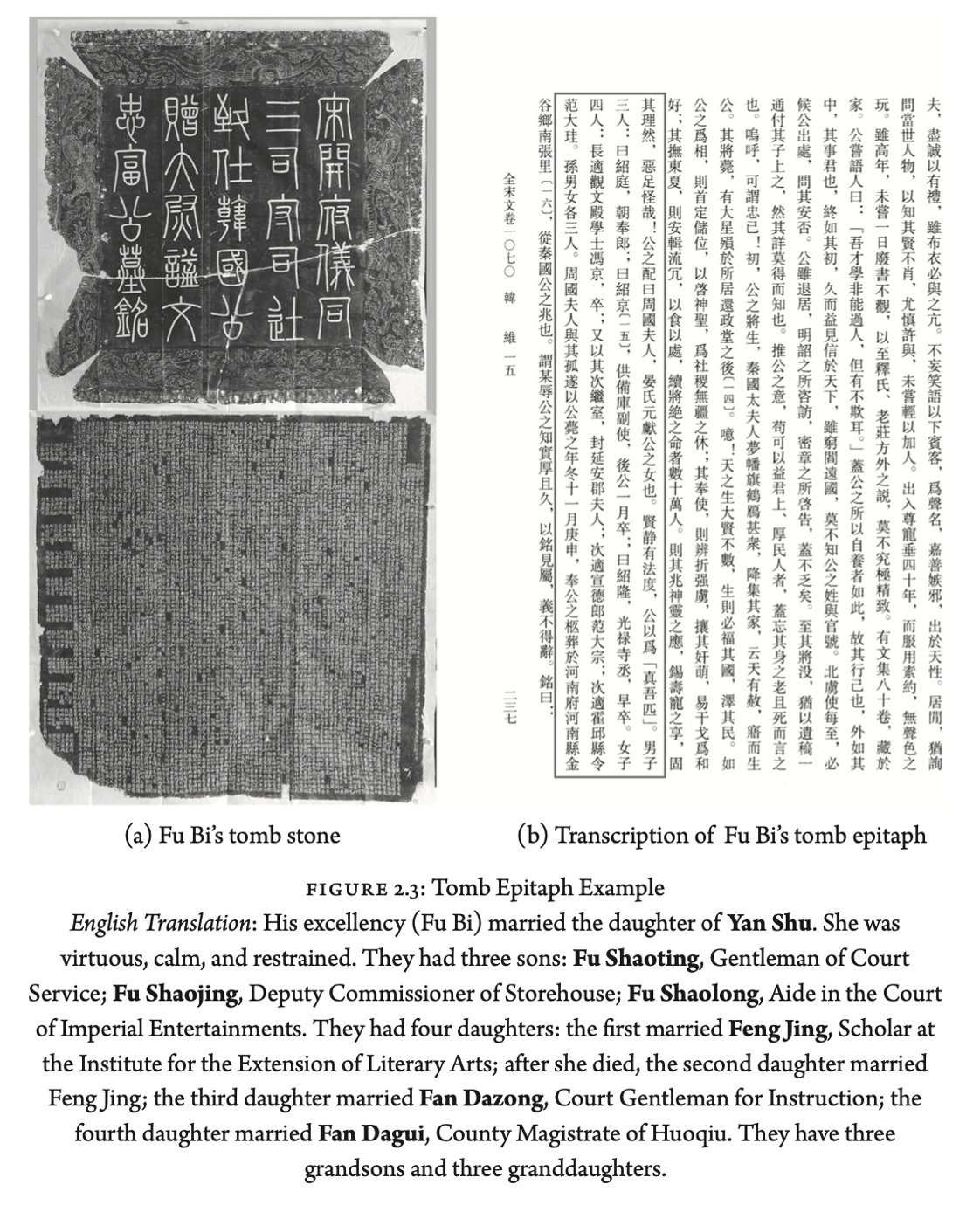

tombstone epitaphs, kinship genealogies, exam records, official dynastic histories, and many databases are used to compile elite networks.

tombstone epitaphs, kinship genealogies, exam records, official dynastic histories, and many databases are used to compile elite networks.

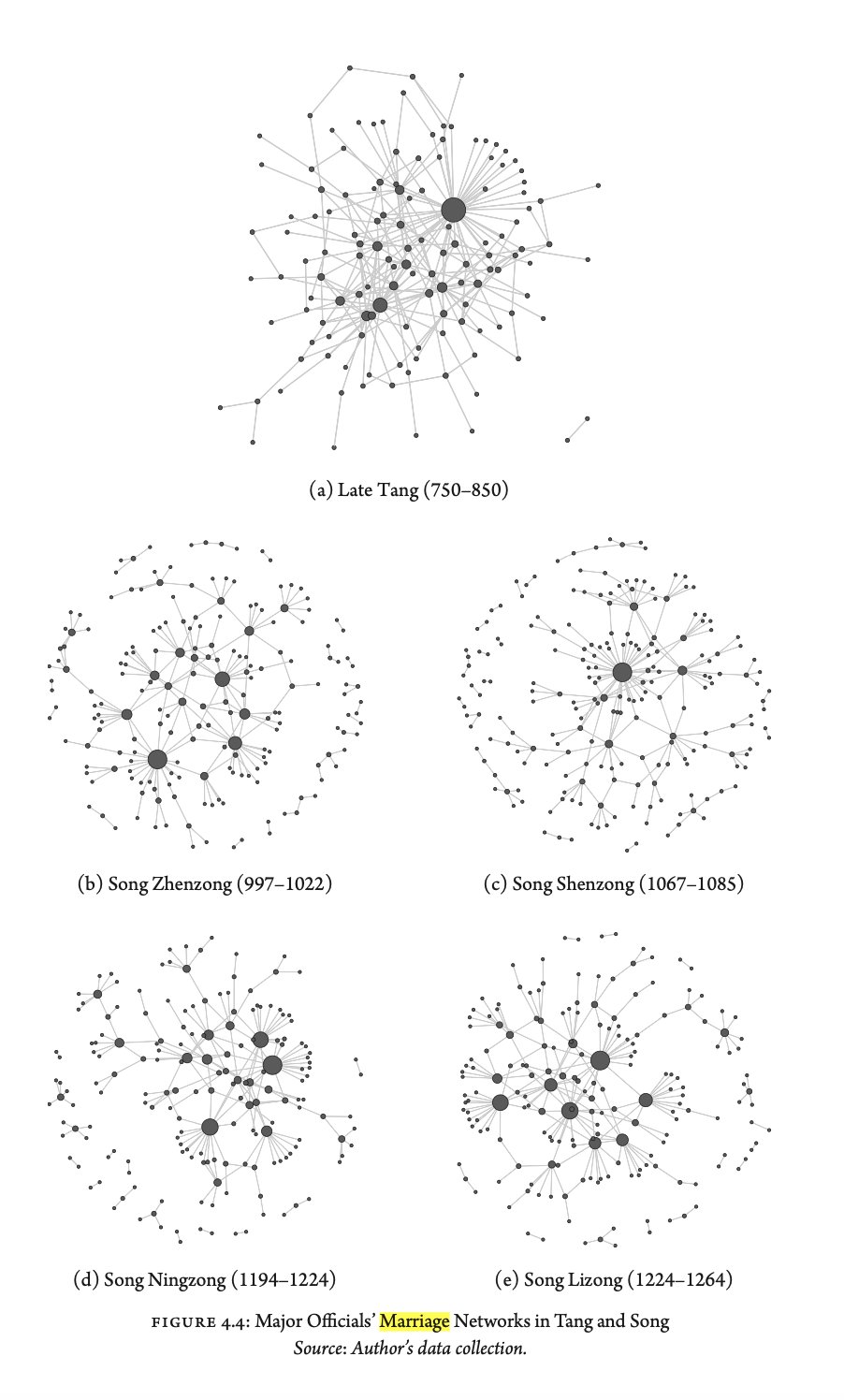

Most important to the author's mission: marriage and kinship networks. This book provides the most comprehensive and up-to-date data analysis of the localization over time of elite social networks in imperial China.

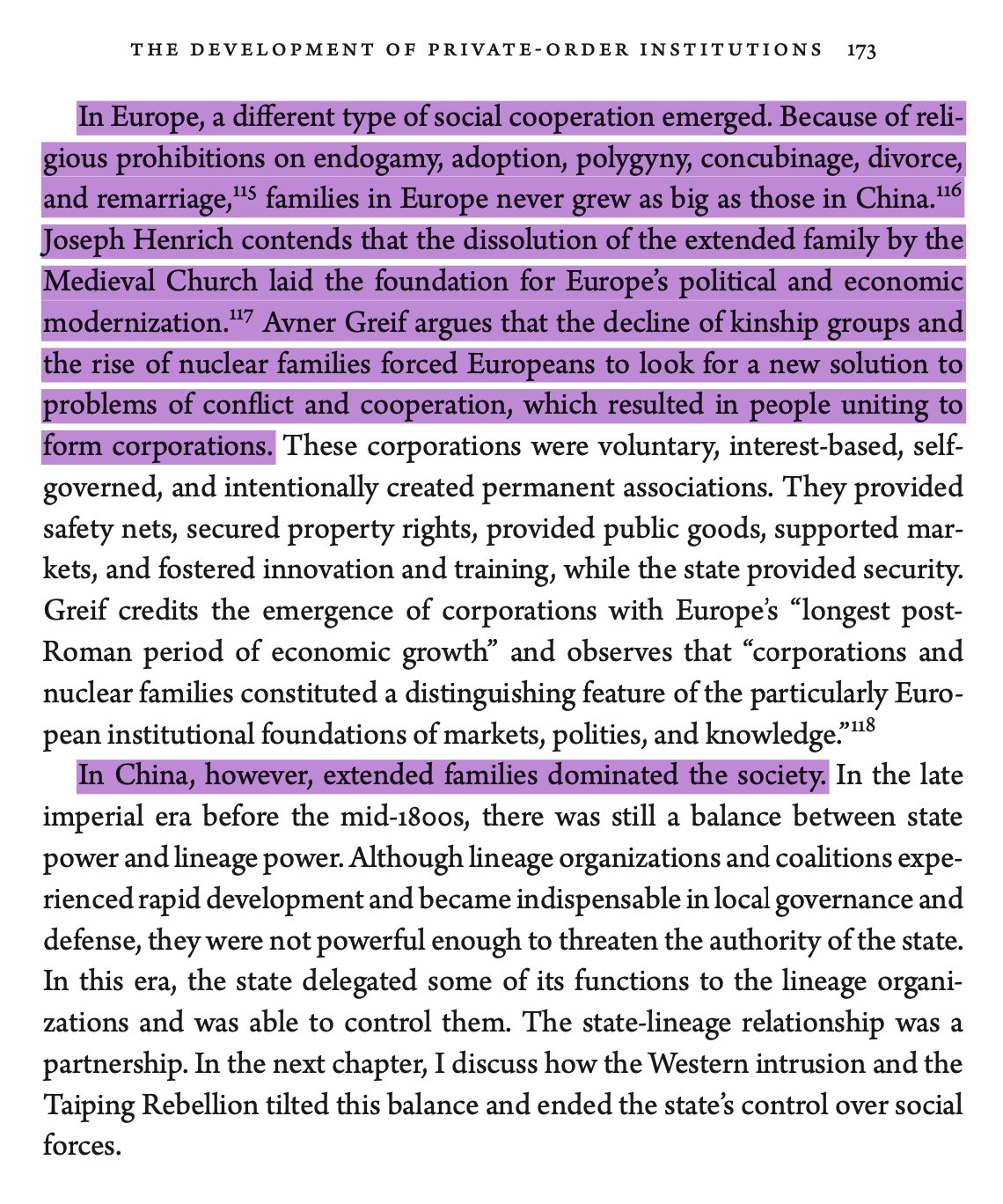

Wang's argument is that increasingly localized kinship and marriage clearly demonstrates the change in elite network structure from star to bow-tie. The importance of social/family structure in determining social development draws on work from Avner Grief and Joseph Henrich.

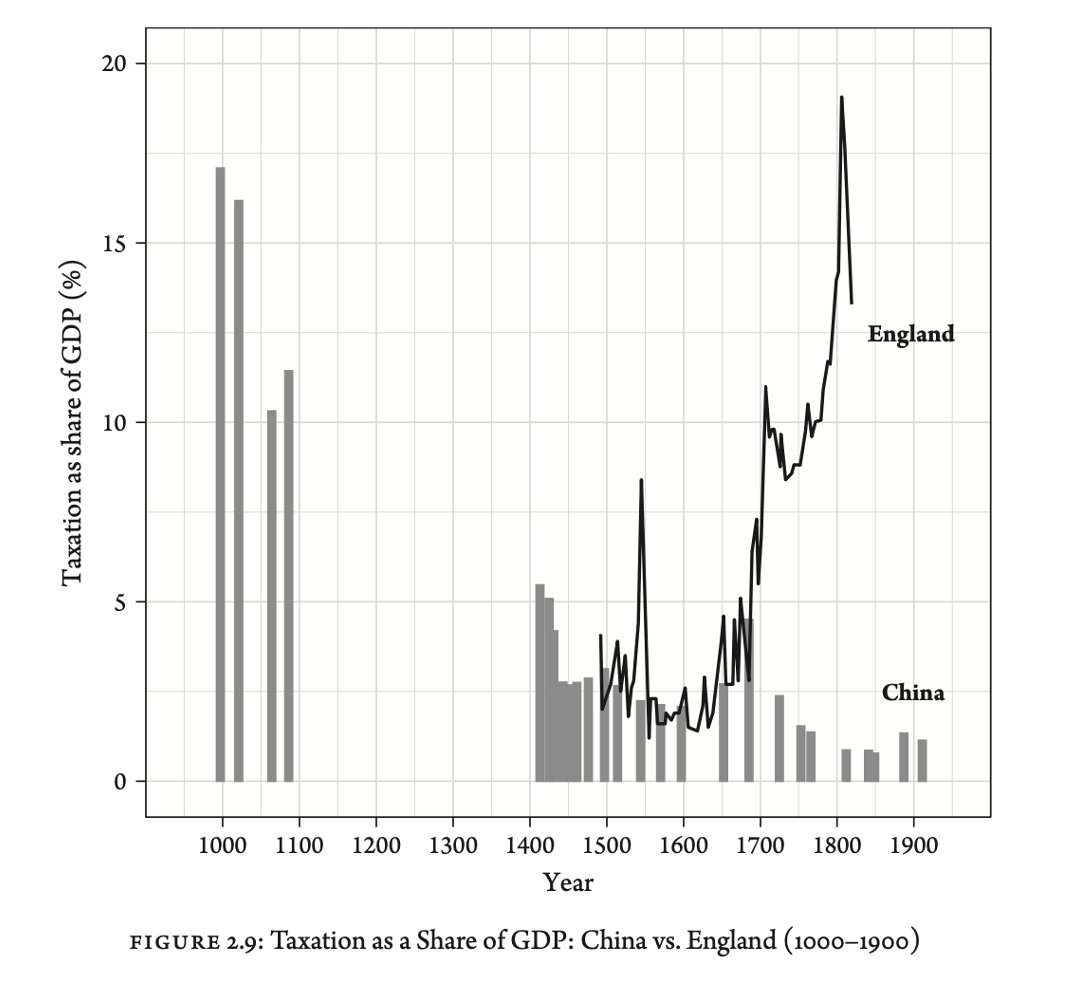

The rise of local lineage institutions is both cause and consequence of diminishing state infrastructural power, per Wang. A key proxy for this long process of "state-involution" per author’s calculations, is taxation as a share of GDP:

China persisted for millennia in this bow-tie network structured, wherein elites were highly fragmented and localized but still drawn toward the center via the omnipresent examination system. A localized class of scholar-gentry captured the state

and dominated the landscape.

and dominated the landscape.

The book terms such sovereign-elite relations “State Maintaining Under Partnership” and considers it the defining characteristic of China’s post-Tang dynastic history. Sovereigns found security in this state of affairs, but state development was reined in by localized interests.

In Wang's assessment, this led to a long period of light touch governance broadly consistent with Walter Schiedel’s canny assessment in his brilliant book “Escape from Rome”

The book brings this home via through-line analysis of attempted state strengthening fiscal reform attempts, e.g. successful reforms in the Tang, partially successful reforms in the Song & Ming (e.g. Wang Anshi & Zhang Juzheng's) and total lack of fiscal reform in the Qing.

Wang argues that contrary to existing explanations, Qing leaders did *try* to pursue state-strengthening fiscal reforms, but were stymied at every turn by a hyper localized elite social network staunchly opposed to strengthening the center's capacity at their own expense.

Critically, the Qing was *never* able to undertake a cadastral survey across its entire 250 year history! Such a survey provides a map of the land...fundamental to acquiring the legibility necessary to undertake basic state functions (recall Scott's work). yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300078152/seeing-like-a-state/

Ultimately the "elite social terrain theory" is well laid out, convincing in one of the author's principles aims, i.e. to “propose elite social terrain as a new variable to gauge long-term state development” not only in China but more generally.

In particular the role of a star type elite social networks in facilitating state development, and bow-tie and ring types in inhibiting it.

One walks away from this book with a new appreciation for the importance of the typology/nature of elite social networks. Far from being a self-seeking cabal, Wang’s book paints a coherent, nationally-oriented elite as absolutely essential for progressive state development.

The importance of such a network recalls Mancur Olson’s theory of an “encompassing organization,” a coalition whose members "own so much of the society they have an important incentive to be actively concern about how productive it is."

www.amazon.com/Rise-Decline-Nations-Stagflation-Rigidities/dp/0300030797

www.amazon.com/Rise-Decline-Nations-Stagflation-Rigidities/dp/0300030797

Yet while the author succeeds in convincing of the importance of elite social terrain, the author fails to convince on another of his central premises: the existence of the *sovereign's dilemma* in Chinese dynastic history.

The author presents elite networks in China as largely shaped by the sovereign. In the conclusion for example, the author states that: “In the short run, the elite social terrain makes the state; in the long run, the state shapes the elite social terrain.”

To me, this affords the sovereign greater influence than he is in truth due. How much influence did the sovereign really have over the typology of elite social networks? Are Chinese sovereigns truly responsible for the localization of elite networks?

the notion that the sovereign shapes elite social terrain does not seem well justified by the book. The first critical period of elite social network change, from star to bow-tie, was not mediated by a sovereign but by the Huang Chao rebellion www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674492059

The second major change, from bow-tie to ring, occurred in the face of tremendous internal and external pressure from the Taiping Civil War and Opium Wars.

The decision to allow local clans and lineages to raise armies (e.g. Zeng Guotan and the Hunanese) was if anything an expedient necessity to enable the state’s persistence than part of any intelligible plan to sustain the sovereign at the expense of state capacity.

As the author states the Qing tried to do state strengthening! But they couldn't.

To me, elite social network appears mostly exogenous. It takes concerted effort to change, and I'm not quite convinced by evidence in this the book that sovereigns acted intentionally to do so.

To me, elite social network appears mostly exogenous. It takes concerted effort to change, and I'm not quite convinced by evidence in this the book that sovereigns acted intentionally to do so.

Ultimately, though, I loved this book! Transgressing academic boundaries to cross-pollinate social science and history, it's a book written after my own heart.

Surely historians will find the book far too brief and partial to capture the nuances of China's broad state development. Societies are much messier than theories of them, of course.

And in trying to simplify our irreducibly complex world to test empirical hypotheses, the book may run into classic a social science risk of oversimplifying multidimensional issues, flattening, missing, or misidentifying temporally & spatially idiosyncratic explanations/factors.

Yet, much as the author “struggled to get a sense of the bigger picture” in his readings of history, does being inundated with an infinite stream of facts bring us closer to a better understanding and appreciation of the world?

Of course, history never merely reflects "facts." Every analysis selects some but not all prior events as having importance and relevance worth noting. Historians get along without examining such assumptions only when if all using the same ones.

As Michael Mann once noted, "everyone operates with some criterion of importance, even if this is rarely made explicit. It can help if we make such criteria explicit from time to time to engage in theory building." www.amazon.com/Sources-Social-Power-History-Beginning/dp/1107635977.