Thread

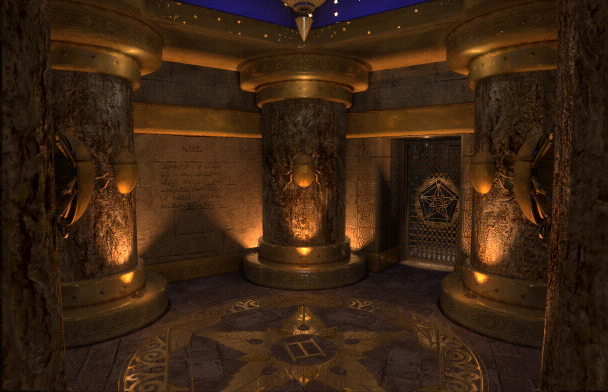

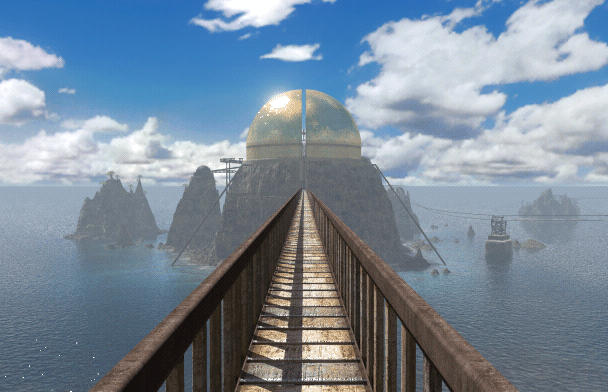

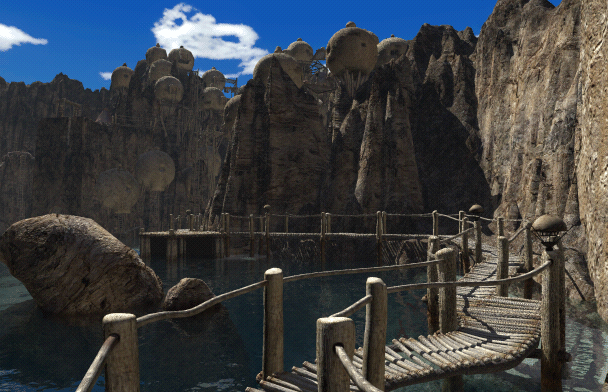

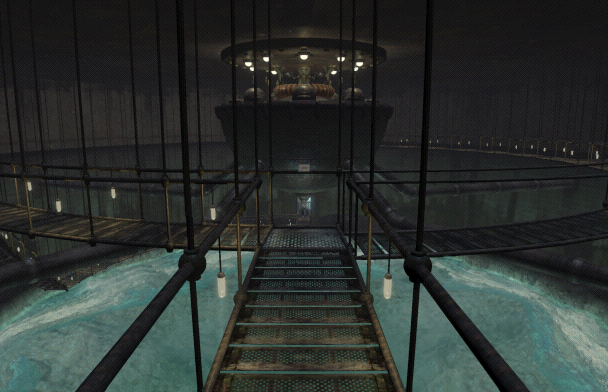

Riven is a really great game. It's maybe the single most immersive game ever made, which is impressive, given it's 25 years old and is presented in a manner only slightly more interactive than a powerpoint presentation — at a 640x480 resolution to boot.

Let me sell you on it.

Let me sell you on it.

The introductory pitch: Riven is an authentic, thoughtfully-designed adventure game filled with beautiful scenery and imaginative architecture, accompanied by a haunting score; an elegant journey with sinister undertones, deeply human writing, and utterly beguiling exploration.

Riven is a puzzle game, which is why it's surprising that when you explore its beautiful islands in the game's first hours, you are unlikely to find any puzzles at all.

You'll merely find several mechanisms, most of which instantly clarify their purpose when experimented with.

You'll merely find several mechanisms, most of which instantly clarify their purpose when experimented with.

Pulling this lever opens that door; pulling that cord draws up this cage.

All of these mechanisms hold the initial mystery of what they're for, but they're certainly not puzzles. They're just part of the world.

All of these mechanisms hold the initial mystery of what they're for, but they're certainly not puzzles. They're just part of the world.

You will also find certain mechanisms whose purpose is yet unclear, or which you may not even recognize as mechanisms; but these are not puzzles either; instead they are mysteries.

Why have mysteries? Why not just use puzzles? I'll tell you why: because Riven prizes immersion.

Why have mysteries? Why not just use puzzles? I'll tell you why: because Riven prizes immersion.

To understand what gives Riven its uniquely immersive quality, let's take a step back and discuss game design philosophy by noting the following.

It is rare for a game to be brave enough to interrogate its own mechanics, and only the very best let this question shape them fully.

It is rare for a game to be brave enough to interrogate its own mechanics, and only the very best let this question shape them fully.

For example: what is combat in a videogame *for*? Why have enemy encounters? Why have weapons? Why do any of this?

Some games answer that question as follows: "Combat is there so you as a player can feel powerful and have a fun time."

Some games answer that question as follows: "Combat is there so you as a player can feel powerful and have a fun time."

These games are, without exception, mediocre experiences at best. Their combat mechanics will not require engaging decision-making; their level design will not create interesting scenarios; their encounters will not be memorable.

The reason for this is that even a string of easy and undifferentiated combats will be enough for most players to "feel powerful and have (moderate) fun." The designers' goals are by this already met; why add complexity that's not needed?

(Of course, testing the game on actual players might show that repetitive combat scenarios bore them. The lesson many designers seem to take from this, is that you should vary your combat with exploration, worldbuilding, rewards, story cutscenes, etc. "Pacing is key," they say.)

(In truth, pacing is only needed when what's there is bad. Good game design does not need to be paced because it does not risk boring the player to begin with.)

A better answer is, "Combat is there to keep the player surprised and on their toes." Such a game would keep encounters fresh, constantly changing their enemy makeup, introducing new elements to the combat, and increasing the complexity of situations you're asked to deal with.

Resident Evil 4 holds this answer, which is why it's a game that, despite being ~80% combat across some 20 hours, is widely known as perhaps the best-paced game ever made.

Another good answer is, "Combat is there to keep the player making interesting and tense decisions." A game like this will utilize resource scarcity, risk-reward systems, different enemies that emphasize different approaches, and so forth. Think Resident Evil 2, or DOOM Eternal.

Unlike the above games, Riven has no combat; it is a puzzle game.

Pause here for a moment. What do you think puzzles are for? What is their value? Why include them? Why not make a walking simulator instead? If immersion is really the goal, why distract the player with puzzles?

Pause here for a moment. What do you think puzzles are for? What is their value? Why include them? Why not make a walking simulator instead? If immersion is really the goal, why distract the player with puzzles?

If your answer is that puzzles are there to provide satisfaction, then I'm pleased to inform you your game is bad. As humans we are doomed to experience a basic level of satisfaction even from very simple puzzles; but "find and hit three hidden markers" does not a good game make.

What answers do other puzzle games have?

Baba Is You says, "puzzles are there to make you think out of the box; to surprise you; to blow your mind." Baba Is You is far too difficult for me, but it's an undeniably good puzzle game; it allowed even an idiot like me to blow my own

Baba Is You says, "puzzles are there to make you think out of the box; to surprise you; to blow your mind." Baba Is You is far too difficult for me, but it's an undeniably good puzzle game; it allowed even an idiot like me to blow my own

mind.

The Witness says, "puzzles are there to make you learn, combine, and apply different ideas." Also very cool. (It even has a 2nd answer, which is that "puzzles are there to show you how information & frameworks shape the way you view the world." Great answer! Great game.)

The Witness says, "puzzles are there to make you learn, combine, and apply different ideas." Also very cool. (It even has a 2nd answer, which is that "puzzles are there to show you how information & frameworks shape the way you view the world." Great answer! Great game.)

Riven's answer to what puzzles are for, is, as far as I'm aware, nearly unique among videogames.

It is this: "The purpose of this game is to immerse you into the world; therefore the purpose of this game's puzzles is to ensure you've immersed yourself fully."

It is this: "The purpose of this game is to immerse you into the world; therefore the purpose of this game's puzzles is to ensure you've immersed yourself fully."

To test whether a player has immersed themselves into the game's world, you do not, in fact, need to throw in a puzzle every five minutes, or even every hour.

Puzzles which crop up with that kind of regularity would either test the player on knowledge another puzzle has already tested them on, or test them on their knowledge of a relatively small part of the world.

The problem with the former is clear; it's simply redundant.

The problem with the former is clear; it's simply redundant.

Meanwhile, the problem with the latter is that it expresses a notion that the game's world is a mere set of separable blocks of information, each of which cleanly fits a given puzzle.

It says: this is a world where you do not need to contextualize information; nor to draw inferences; nor to pay attention to parts of the world that aren't needed to solve the puzzle; and so forth. In short: it fails to encourage the player to immerse themselves into the world.

Enter Riven: a 15-hour puzzle game which only contains two real puzzles.

It has two puzzles not because it's cheap; this was 1997's best-selling game, and it was financed under that expectation. Its predecessor, after all, was the world's best-selling videogame for *nine years*.

It has two puzzles not because it's cheap; this was 1997's best-selling game, and it was financed under that expectation. Its predecessor, after all, was the world's best-selling videogame for *nine years*.

Its designers knew what they were doing. Riven has two puzzles, because its creators understood that two sufficiently puzzles wholly suffice to test the player's understanding of the world as a whole.

The puzzles take mere seconds to solve. The remaining hours of gameplay is spent simply immersing yourself into the world completely, until you finally understand what you're being tested on — in large part because you'll slowly grow to understand *why* you're being tested on it.

In the natural world, puzzles simply don't exist. So how do you create a realistic world that has any puzzles at all? I won't spoil Riven's answer here; but suffice to say that the two puzzles have excellent in-universe reasons for existing; their presence itself tells a story.

Riven, not intent merely to have an answer for what puzzles are for, went even further than this and asked itself: what are clues for?

In Myst, its predecessor, many clues were simply direct keys to the puzzle's locks: codes or solutions that were handed to you cleanly, and all you had to do was do the mental equivalent of inserting the key and turning it.

In Riven, clues are often inherently incomplete; to translate the clues you find into solutions you can use, you'll need to think about what the clues represent and how they relate to what you know of the world.

In fact, the better your understanding of the world, the more the world reveals itself to be organically filled with small clues — clues which were always right there, in the open, waiting for you to guess that they are there, to come check, and finally to confirm their presence.

Thus Riven's clues, in their subtlety and incompleteness, are both reward and requirement for immersing yourself ever more deeply into the game's world.

Riven is known as a difficult game, and it is. But it's not difficult the way other puzzle games are difficult. You won't need to do anything that amounts to spectacularly complex mental calculations; and you won't need to make wild, illogical, or annoyingly specific guesses.

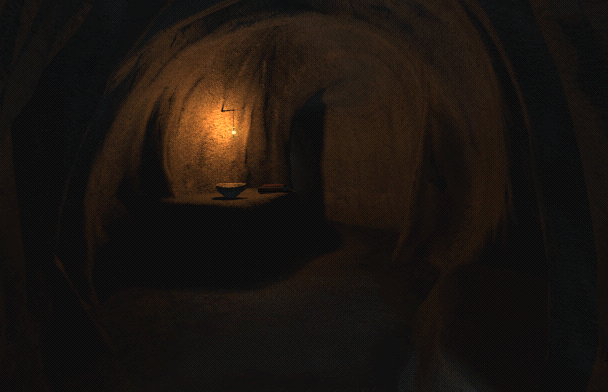

Instead, Riven is difficult because until such a point where you can very nearly solve the puzzles, you won't know what information could possibly be needed to solve them. Even finding the puzzles requires close inspection of the game's world. So the only thing to do is to Look.

And this, you'll realize, is something nearly no other game has ever asked you to do.

Games nowadays are visually designed in ways that clarify how to interact with them. Colour-coded pickups; blinking interactables; detective vision; even clearly moving enemies...

Games nowadays are visually designed in ways that clarify how to interact with them. Colour-coded pickups; blinking interactables; detective vision; even clearly moving enemies...

All such elements essentially grab your attention and direct it *for* you. This is often good: DOOM Eternal casts an invisible and wholly unrealistic light on its demons to ensure they remain clearly identifiable even in dark spaces, which keeps you in the flow of decisionmaking.

But insofar as games do this kind of thing, they're facilitating only a single type of play: one sourced in effortful focus. They throw information at you; it's your job to take that information in and use it in your play. The game provides the stream which you filter and act on.

But another type of play is possible: one borne from open awareness. Here, instead of playing with set intentions, you simply wander around, letting your awareness expand from what you'd usually focus on and be filled with the world.

Not an agentive act, but a receptive one.

Not an agentive act, but a receptive one.

Motivated by a problem that needs solving, but unconstrained by any direction, you are finally free to immerse yourself in the world at hand. All that is there to do, is to attend to its beautiful details and its beguiling mysteries.

Reader, it's an incredible experience.

Reader, it's an incredible experience.

Here comes the part where you will wrongly, erronously, and indeed incorrectly assume the game isn't for you: for this approach of paying attention to work well within the game's world, where clues are geographically dispersed, it's practically required to take detailed notes.

I procrastinated on Riven for years because manually taking notes while playing a game sounded so cumbersome. Do not repeat my mistake: taking notes was some of the most fun I've had in a game. It encouraged me to better notice even small details, which is... simply really nice!

Taking notes engenders a more engaged and immersed way of playing a game. It would be awkward if there were in-game time pressures, but Riven has no action sequences whatsoever; and it would get overwhelming if the game were huge, but Riven's world is mercifully compact.

Taking notes, paying close attention, carefully considering the information you're getting... All of these may sound like a lot of effort. But it may also be true that you have been *wanting* a game that fully rewards and indeed is designed around deep and genuine engagement.

If you've come this far, chances are you *like* to engage in things; you *like* to think about details; you *like* to immerse yourself. Riven is your chance: it's complex enough to require all those things, but is by no means a big game. You are certainly capable of beating it.

———

As for the game's age: its graphics have a beautiful and lively style that is unusual nowadays, whose consistency sells the world's realism; and its image-based nature means loading is lightning-fast. Its traversal speed in particular puts even modern games to shame.

As for the game's age: its graphics have a beautiful and lively style that is unusual nowadays, whose consistency sells the world's realism; and its image-based nature means loading is lightning-fast. Its traversal speed in particular puts even modern games to shame.

Some story notes to get you up to speed:

* Certain people can "write Ages" (create worlds) which may be traveled to through the use of books that "link" to these worlds.

* The man in the introductory cinematic is Atrus. The books you start with are his; read them for context.

* Certain people can "write Ages" (create worlds) which may be traveled to through the use of books that "link" to these worlds.

* The man in the introductory cinematic is Atrus. The books you start with are his; read them for context.

And some technical notes:

* Don't fear reviews complaining about technical issues; the game was patched recently, and now runs on modern systems perfectly fine.

* A remake is coming. But the game is perfect in its current format, and some design choices may not survive an update.

* Don't fear reviews complaining about technical issues; the game was patched recently, and now runs on modern systems perfectly fine.

* A remake is coming. But the game is perfect in its current format, and some design choices may not survive an update.

Whatever you do, see if you can refrain from looking up any kind of walkthrough. This is a game where even getting stuck and fully restarting years from now will be worth more than spoiling yourself in the present day. It's a one-of-a-kind experience. Enjoy.

If you enjoyed reading my thoughts on Riven, you might also like my post about Dark Souls... www.resetera.com/threads/dark-souls-is-a-powerful-metaphor-for-depression.44163/

... and my Rain World longread: experiencedmachine.wordpress.com/2019/09/16/rain-world-reaching-enlightenment-through-unfairness-intr...