Thread by The Cultural Tutor

- Tweet

- Jan 3, 2023

- #Art #Architecture

Thread

Mosques are filled with complex geometry, kaleidoscopic colour, and intricate ornamentation.

Why do they look like that?

Why do they look like that?

Some of the world's most beautiful buildings are mosques, and they have been for centuries.

And even while their exteriors are striking, it is inside where their beauty fully reveals itself.

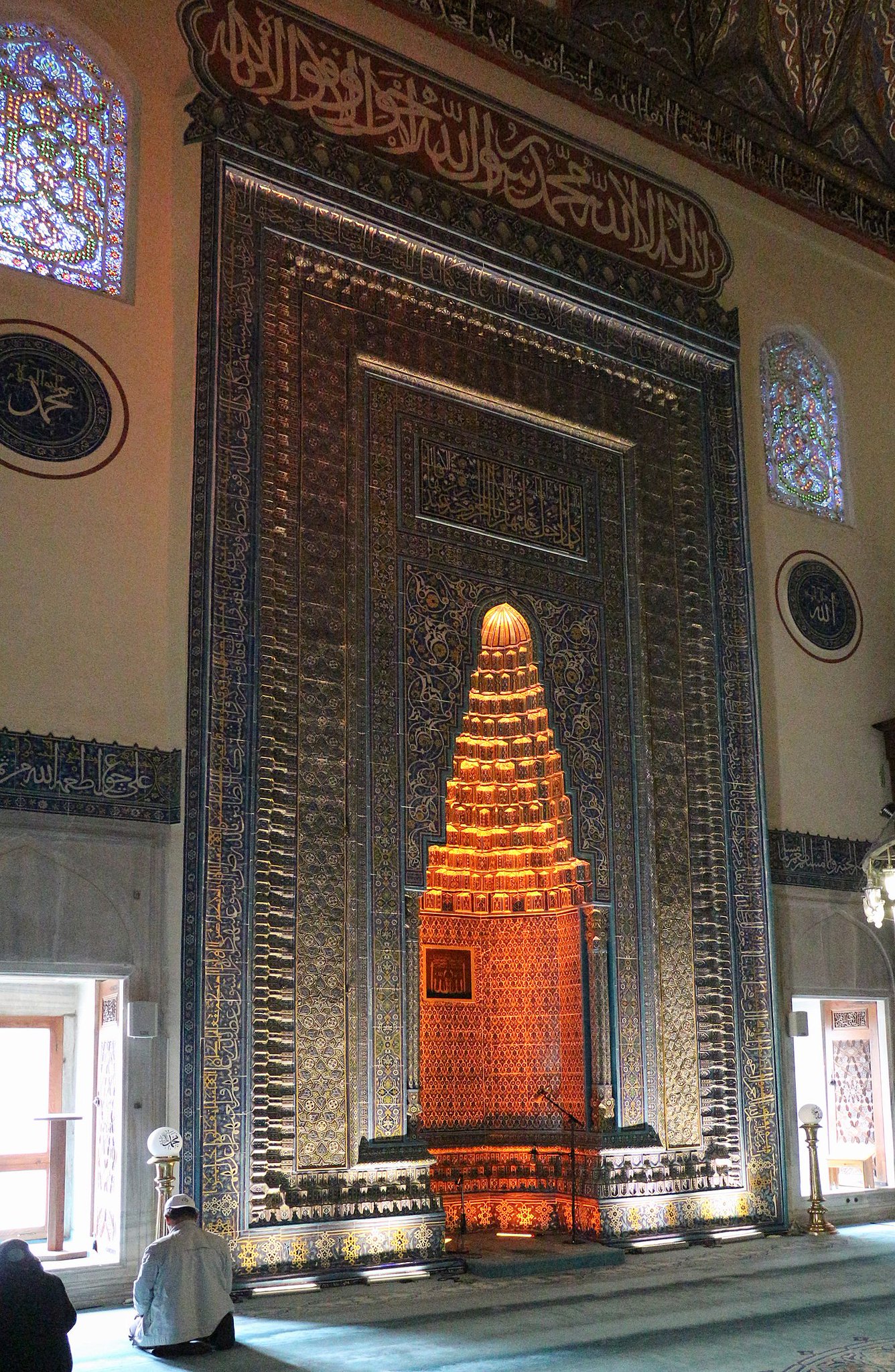

Consider Istanbul's Sultan Ahmed Mosque, known as the Blue Mosque, completed in 1616:

And even while their exteriors are striking, it is inside where their beauty fully reveals itself.

Consider Istanbul's Sultan Ahmed Mosque, known as the Blue Mosque, completed in 1616:

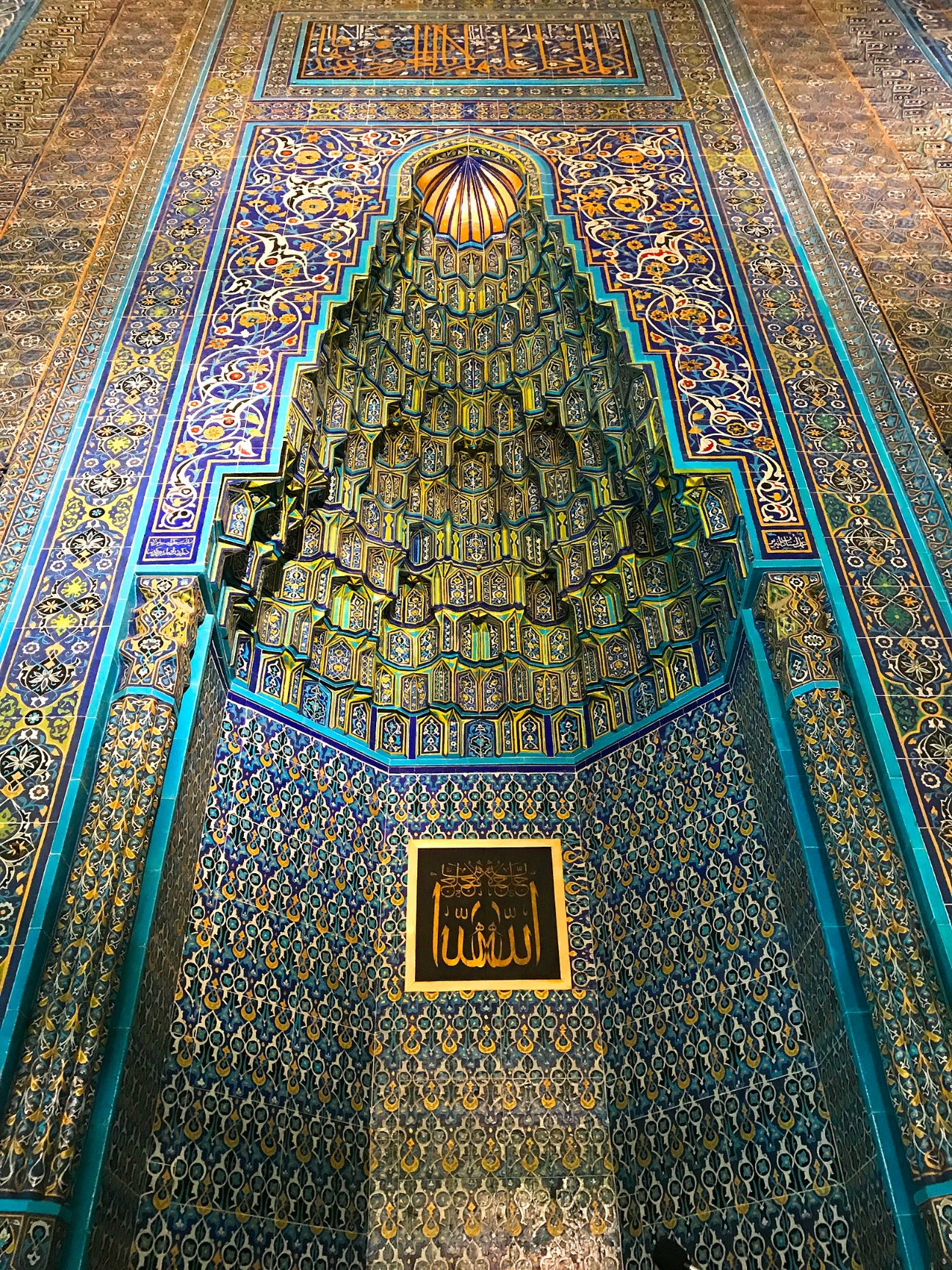

Or the Shah Jahan Mosque in Thatta, Pakistan, which takes its name from the Mughal Emperor who had it built in the 17th century.

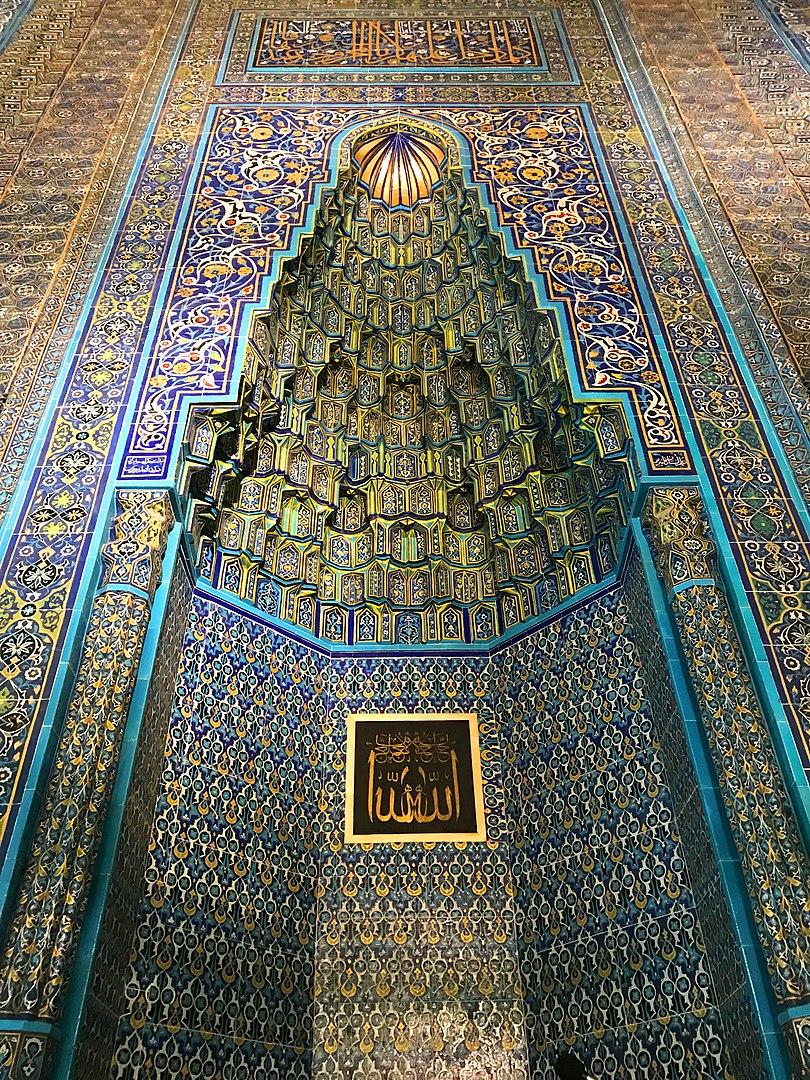

Or the Green Mosque in Bursa, Turkey, commissioned by Sultan Mehmed I and completed in 1423.

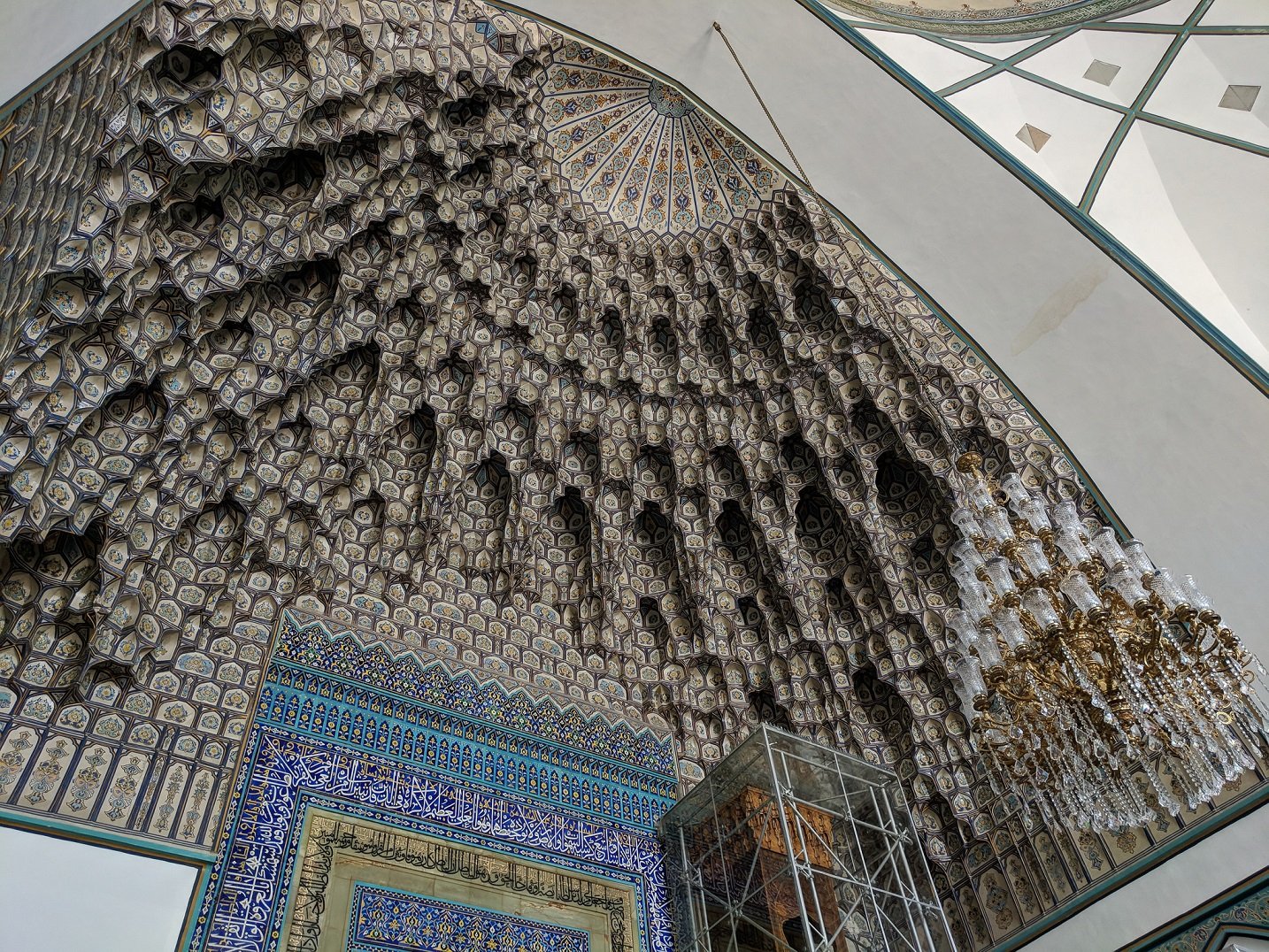

Its mihrab - which indicates the direction of prayer - is a miracle of mathematical intricacy and polychromatic delight.

Its mihrab - which indicates the direction of prayer - is a miracle of mathematical intricacy and polychromatic delight.

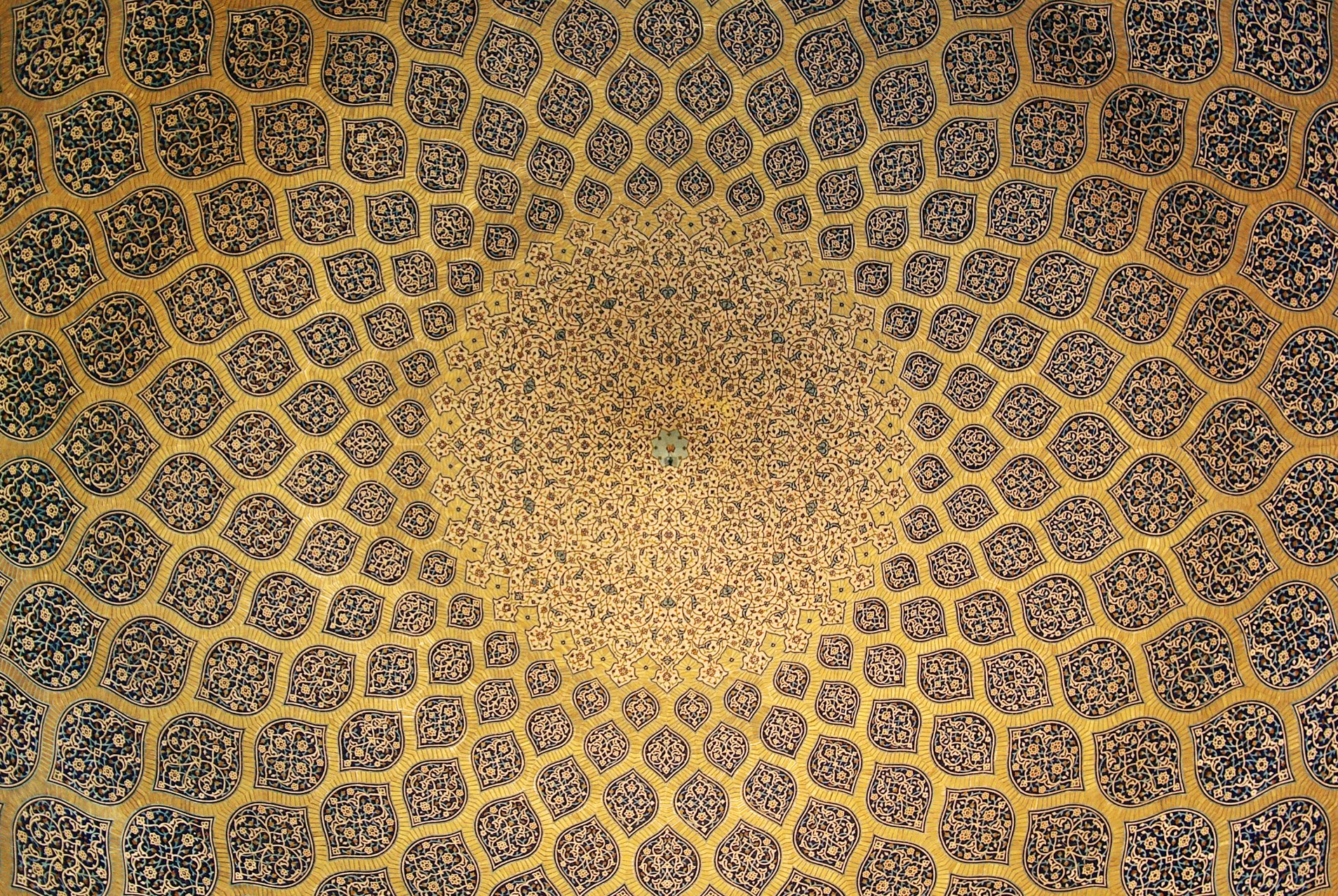

Or Iran's Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, built by the Safavid Empire in 1619.

Its interior, overflowing with sumptuous colours and fluid floral motifs, almost seems to be alive and moving.

Its interior, overflowing with sumptuous colours and fluid floral motifs, almost seems to be alive and moving.

These are but four examples of the world's many great mosques, which surely represent some of humanity's foremost artistic achievements.

But why do they look like that? Why the complex patterns, elaborate geometry, and emphasis on colour?

The answer is simple...

But why do they look like that? Why the complex patterns, elaborate geometry, and emphasis on colour?

The answer is simple...

Representational art - the depiction of humans, animals, or any religious figures or sentient beings - has been avoided or outright prohibited for centuries in religious Islamic art.

The avoidance of representational art is known as "aniconism".

The avoidance of representational art is known as "aniconism".

And it's not uncommon for religious art to be aniconistic.

The word "iconoclast" comes from the 8th century, when the Byzantine Emperor Leo III banned representational religious art and started a movement whereby existing representational religious images were destroyed.

The word "iconoclast" comes from the 8th century, when the Byzantine Emperor Leo III banned representational religious art and started a movement whereby existing representational religious images were destroyed.

And after the Reformation in 16th century Europe representational art was forbidden in many churches, seen as a form of Catholic idolatry which departed from the message of the Bible.

Many cathedrals had all their art, representational or otherwise, taken away.

Many cathedrals had all their art, representational or otherwise, taken away.

But these were, broadly, exceptions rather than rule. In Islam the avoidance of representational art has been there since the beginning, as established in the hadiths.

It was considered idolatrous, and a blasphemous infringment on the divine act of creation.

It was considered idolatrous, and a blasphemous infringment on the divine act of creation.

Aniconism is not an absolute in Islamic art. For example, the great tradition of secular Ottoman and Persian miniatures, made for kings and courts, are filled with humans and animals and scenes from ordinary life.

But mosques, religious in nature, were aniconistic monuments.

But mosques, religious in nature, were aniconistic monuments.

And so artists had to find other ways of decorating them.

They turned to colour, geometry, and pattern rather than figurative representation. Things started out relatively simple, as seen here in Tunisia's 9th century Great Mosque of Kairouan:

They turned to colour, geometry, and pattern rather than figurative representation. Things started out relatively simple, as seen here in Tunisia's 9th century Great Mosque of Kairouan:

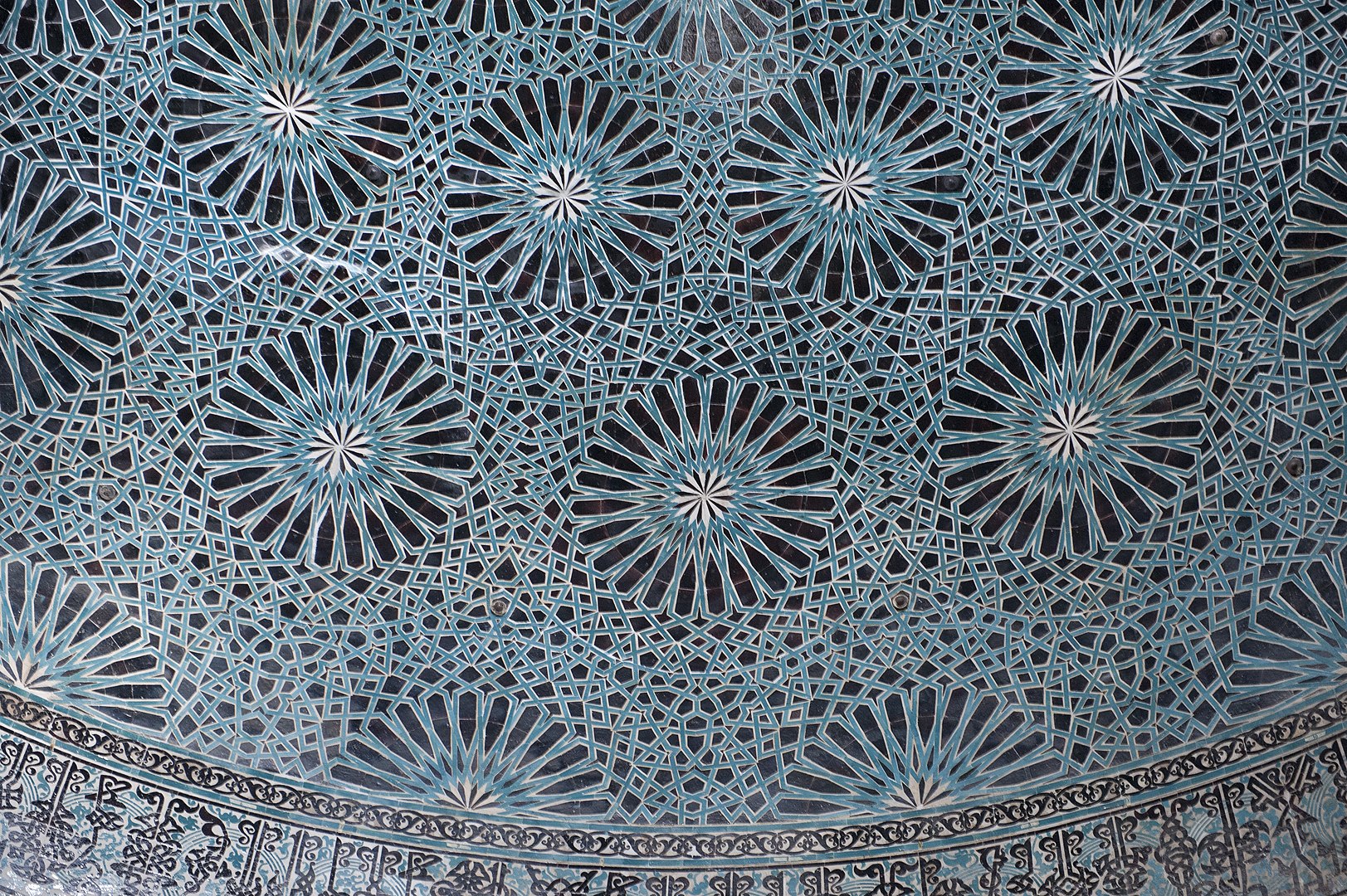

But soon enough artists had mastered the creation of elaborate, abstract geometrical patterns.

What astonishes most is the overwhelming mathematical precision of these designs, as in the 13th century Karatay Madrasa in Konya.

What astonishes most is the overwhelming mathematical precision of these designs, as in the 13th century Karatay Madrasa in Konya.

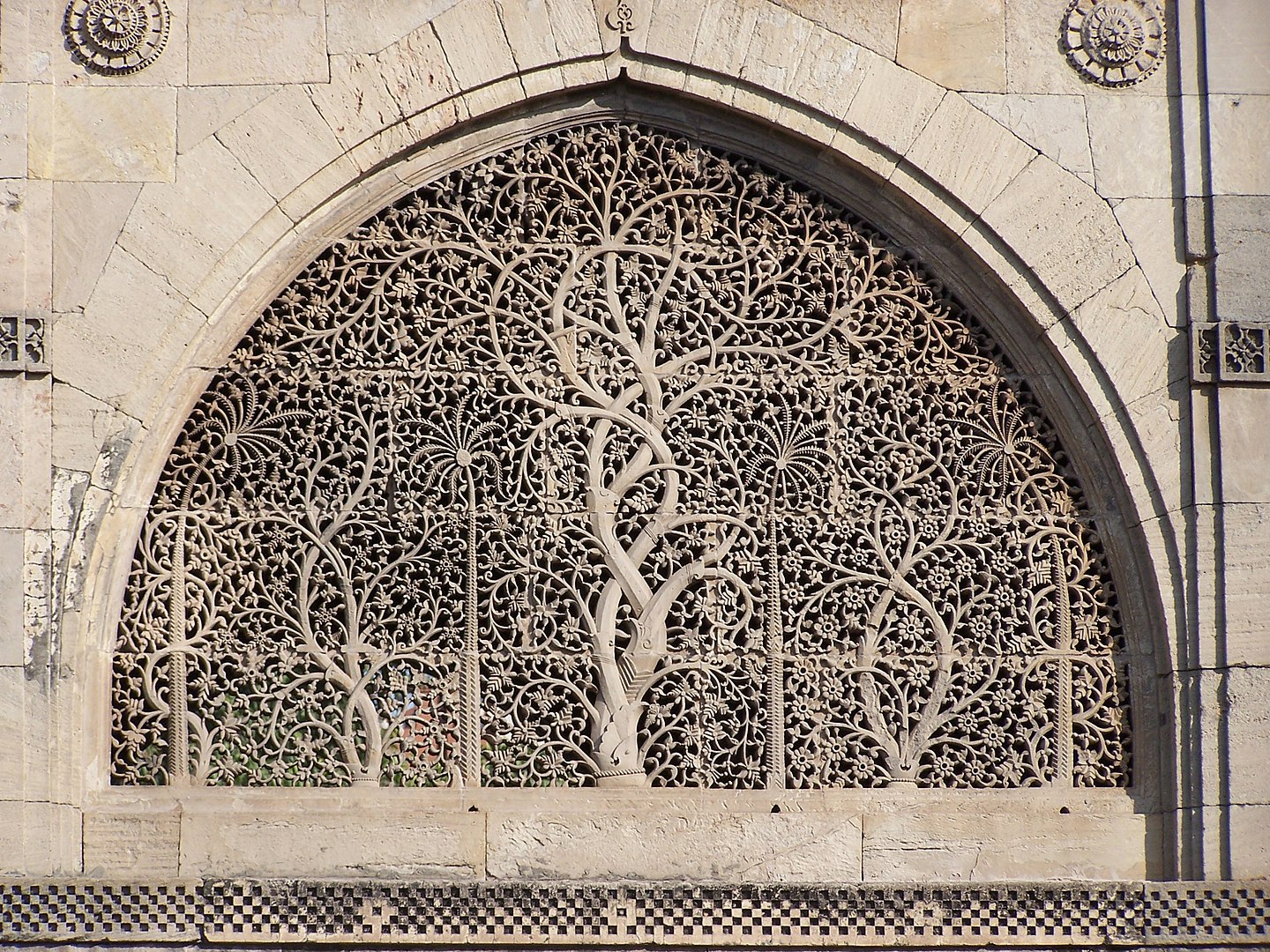

But it wasn't all completely abstract. Plants and flowers were not considered idolatrous, and so floral motifs worked their way into Islamic art, as in the 17th century Badshahi Mosque in Lahore, built from white marble and red sandstone.

The muqarnas was also developed, a method of decorating arches with honeycomb-like layers of receding miniature geometry, dissolving solid forms into thin air.

The artists' restriction had become their greatest ally in creating beautiful architecture.

The artists' restriction had become their greatest ally in creating beautiful architecture.

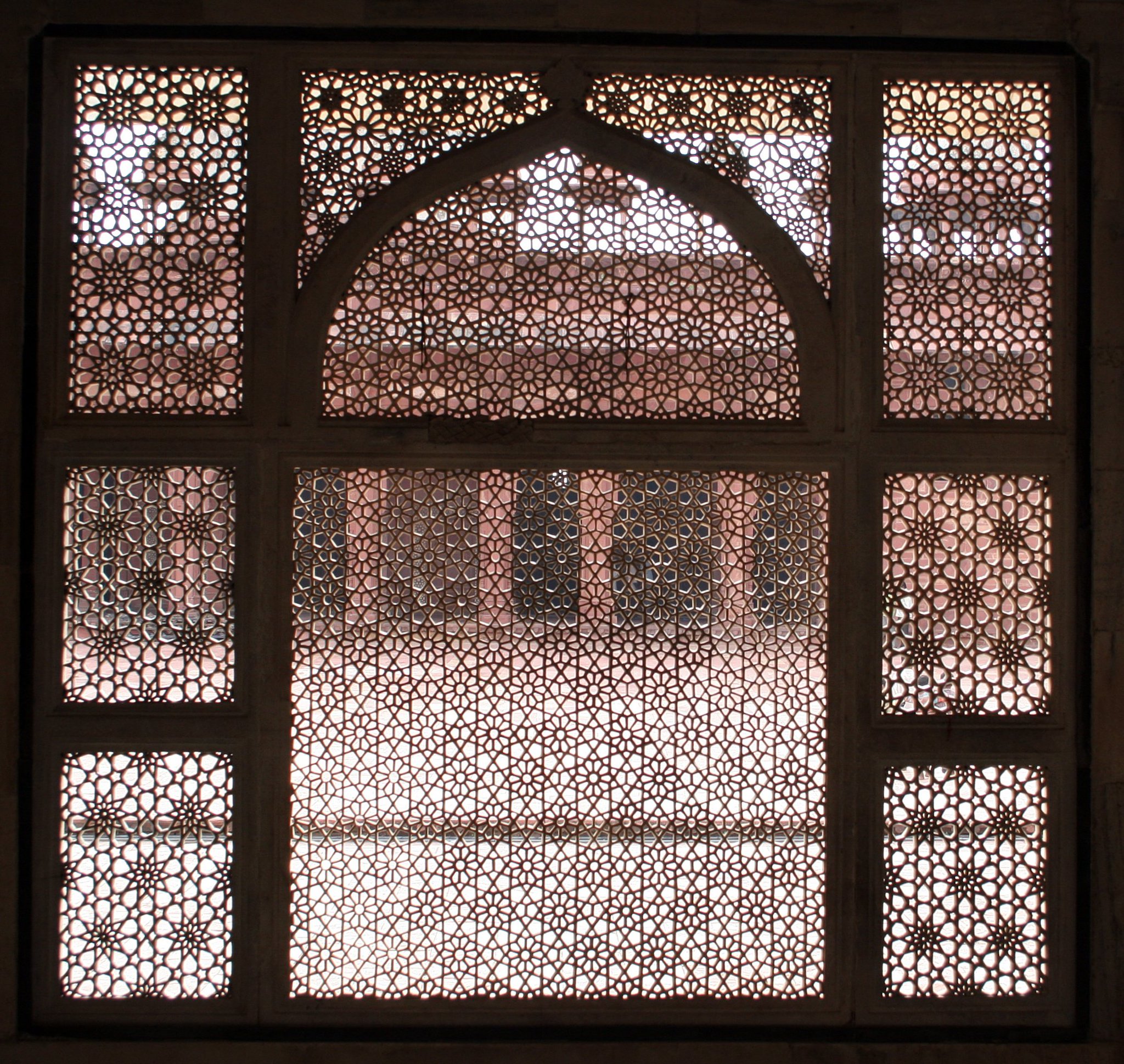

So too appeared the jali, a type of lattice screen made from wood or stone, delicately carved and no less intricate than the tiles or paintings.

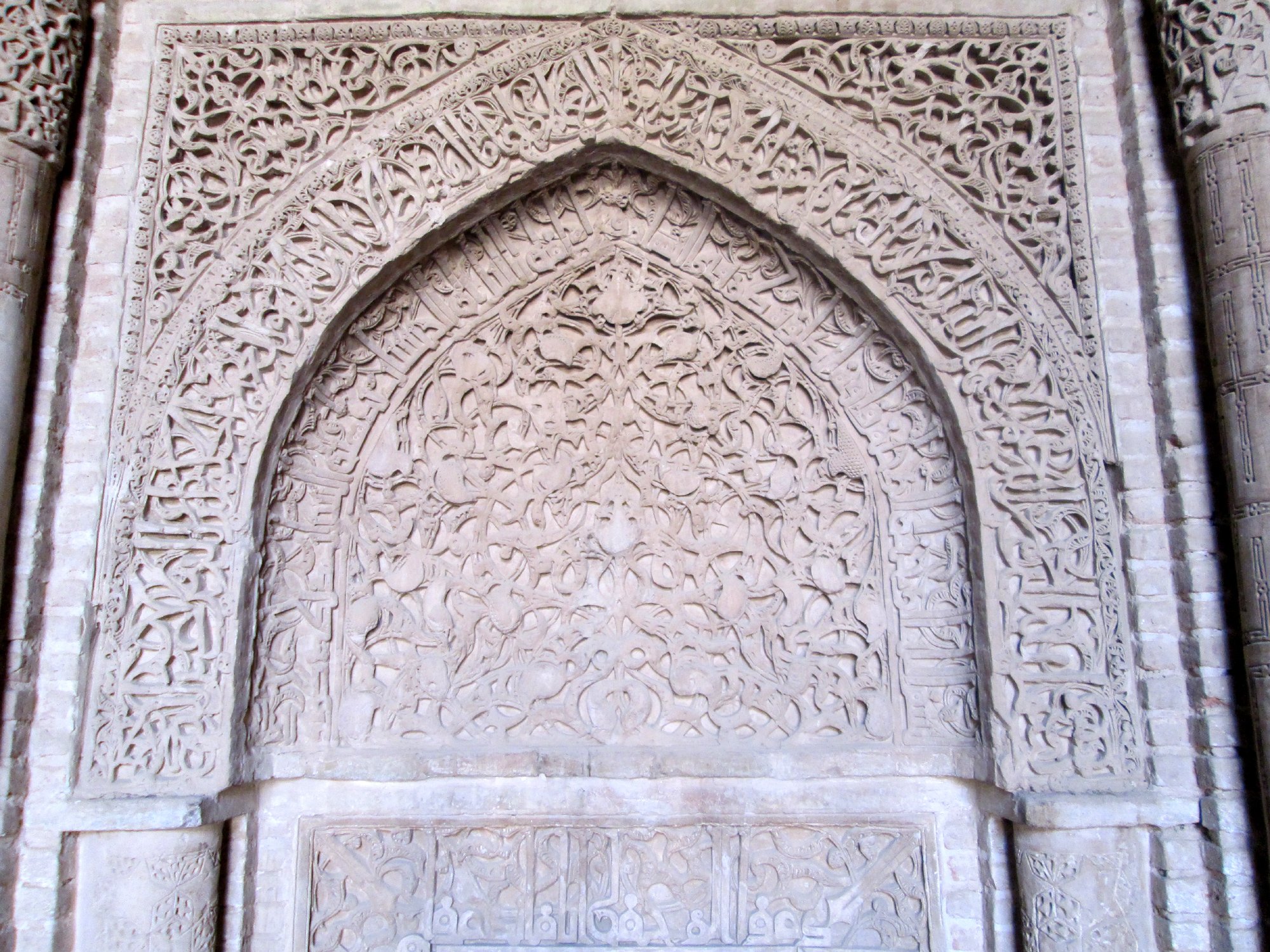

Arabic calligraphy was also used as a method of decoration, turning the written word into an art form all of its own.

See here, in the 11th century Jameh Mosque of Ardestan, how Arabic script and floral patterns almost become one.

See here, in the 11th century Jameh Mosque of Ardestan, how Arabic script and floral patterns almost become one.

But all this wasn't just for the sake of it - mosques are religious buildings with an overriding purpose.

The icons of Orthodox cathedrals and the frescoes of Catholic churches aren't there just to look pretty - they tell religious stories and serve an ecclesiastical purpose.

The icons of Orthodox cathedrals and the frescoes of Catholic churches aren't there just to look pretty - they tell religious stories and serve an ecclesiastical purpose.

The geometric patterns used to decorate mosques, fractal in their complexity and overwhelming in their magnitude, were intended as an abstract vision of the might of divine creation and the inherent mathematical coherence of a designed universe.

Abstraction draws one to think of the immaterial, to move beyond the physical world - the divine was more immediate without any figurative intermediary.

This, at least, was how the non-representational art of mosques came to be interpreted and understood.

This, at least, was how the non-representational art of mosques came to be interpreted and understood.

Mentions

See All

Susan Cain @susancain

·

Jan 3, 2023

This is a magnificent thread