Thread by The Cultural Tutor

- Tweet

- Dec 22, 2022

- #Architecture #Art

Thread

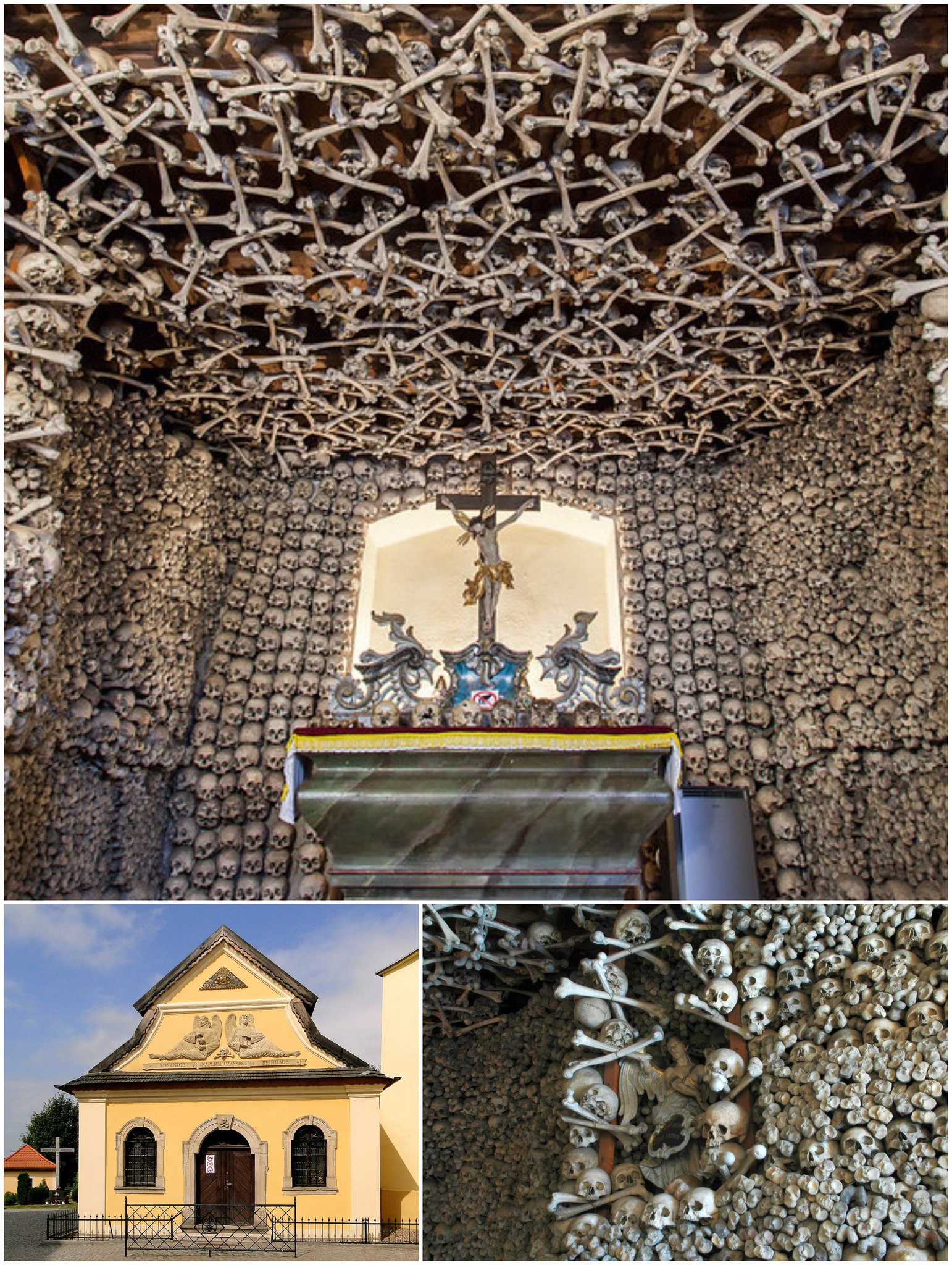

This small church in Poland might look ordinary, but inside is a chapel made of human skeletons.

It took one man eighteen years to build. Why did he do it?

It took one man eighteen years to build. Why did he do it?

This is the exterior of St. Bartholomew's Church in Kudowa, Poland. A rather modest Baroque building, and not one that immediately stands out as anything unusual.

But, upon closer inspection, the decorative reliefs and the carving on the keystone above the door reveal a clue as to what lies within...

A chapel decorated with three thousand skulls and thousands more bones, with twenty one thousand skeletons interred below.

They were collected, cleaned, and arranged by the priest Václav Tomášek over the course of eighteen years from 1776 to 1794.

They were collected, cleaned, and arranged by the priest Václav Tomášek over the course of eighteen years from 1776 to 1794.

The region had been ravaged by war, disease, and famine.

The Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), the Silesian Wars (1740-1763), the Seven Years' War (1756-1753) and countless more minor conflicts, along with cholera epidemics, other plagues, and famine had killed thousands.

The Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), the Silesian Wars (1740-1763), the Seven Years' War (1756-1753) and countless more minor conflicts, along with cholera epidemics, other plagues, and famine had killed thousands.

And so the region was filled with mass graves.

With people dying at such a rate and without the space or resources for proper burials, they had been disposed of as quickly as possible.

With people dying at such a rate and without the space or resources for proper burials, they had been disposed of as quickly as possible.

But Václav Tomášek, with the help of a gravedigger, travelled around the region to discover these mass graves.

He collected the bones, cleaned them, and used them to decorate St Bartholomew's. He gathered so many skeletons that most were simply interred beneath the church.

He collected the bones, cleaned them, and used them to decorate St Bartholomew's. He gathered so many skeletons that most were simply interred beneath the church.

And so the Skull Chapel of St Bartholomew's is an ossuary - a place for the collection and storage of bones.

And that isn't unusual; they've been around for thousands of years. Though, in most cases these ossuaries were not decorative but functional spaces.

And that isn't unusual; they've been around for thousands of years. Though, in most cases these ossuaries were not decorative but functional spaces.

So why the decoration?

Well, St Bartholomew's Church wasn't the first ossuary to use skeletons artistically.

Václav Tomášek had visited the Capuchin Crypt in Rome, where the bones of deceased friars had been used ever since 1631 to decorate its walls:

Well, St Bartholomew's Church wasn't the first ossuary to use skeletons artistically.

Václav Tomášek had visited the Capuchin Crypt in Rome, where the bones of deceased friars had been used ever since 1631 to decorate its walls:

Our Lady of the Conception of the Capuchins is the full name of the church, one which is also decorated with paintings by some of the greatest artists of the day, including Guido Reni and Pietro da Cortona:

Seeing such beautiful art then, and beneath it a crypt decorated with skeletons of members of the Capuchin order, arranged with such care and delicacy, it's easy to see why Tomášek was inspired to do something with the discarded bodies of the mass graves in his homeland.

But nor are these the only two such ossuaries.

There's the San Bernardino alle Ossa in Milan, built in 1712, on an even grander and more formal scale than the others.

There's the San Bernardino alle Ossa in Milan, built in 1712, on an even grander and more formal scale than the others.

Which itself so inspired King John V of Portugal on a visit there that he had one built in his own kingdom - the Capela dos Ossos in in Évora.

In which there is a poem, written by a priest, which gives us a clue as to the purpose of all this:

"Recall how many have passed from this world,

Reflect on your similar end.

There is good reason to do so;

If only all did the same."

"Recall how many have passed from this world,

Reflect on your similar end.

There is good reason to do so;

If only all did the same."

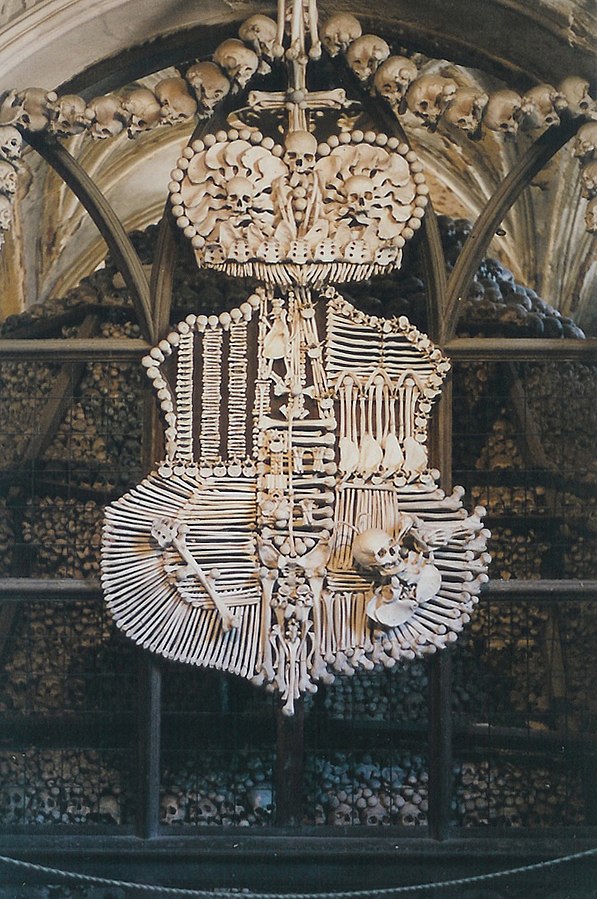

Then there's the Sedlec Ossuary in the Czech Republic.

Its crypt had been little more than a storage facility for exhumed skeletons - over 50,000 of them - until the woodcarver František Rint was commissioned to do something with them in 1870.

The result was rather striking:

Its crypt had been little more than a storage facility for exhumed skeletons - over 50,000 of them - until the woodcarver František Rint was commissioned to do something with them in 1870.

The result was rather striking:

Compared to the grand scale and order of the San Bernadino, or to Tomášek's ossuary - which looks like the work of a non-artist labouring with care to create something cohesive - the Sedlec Ossuary feels like the work of a skilled craftsman.

And there's also the Basilica of St Ursula in Cologne, whose "Golden Chamber" has walls decorated with mosaics made from skeletons.

So why all these chapels made from bones, these decorated ossuaries?

Well, ever since the Black Death in the mid-14th century Europe had been fascinated by death. The plague's devastation had left an indelible mark on the continental psyche.

Well, ever since the Black Death in the mid-14th century Europe had been fascinated by death. The plague's devastation had left an indelible mark on the continental psyche.

People were aware of life's fragility more than ever before.

In the early 1400s the Ars Moriendi - the "Art of Dying" - was published, a literal guide to dying well complete with suggested questions, recommended behaviour, consolations, and illustrations.

In the early 1400s the Ars Moriendi - the "Art of Dying" - was published, a literal guide to dying well complete with suggested questions, recommended behaviour, consolations, and illustrations.

This fascination with mortality entered art and became known as the "Danse Macabre," walking a fine line between dark humour and morbidity, between a terrifying vision of death and a striking reminder that life is short and worth cherishing while we have it.

Motifs of death - memento mori - permeated European art for centuries, whether as skulls in paintings, tomb sculptures of decaying corpses, or in more symbolic ways like hourglasses.

St Bartholomew's - and the other ossuaries - are all of that taken to another level.

St Bartholomew's - and the other ossuaries - are all of that taken to another level.

Seen in this way, Tomášek's eighteen year labour makes more sense.

Living in an era ravaged by death, he perhaps sought a way to deal with it, to get something from all that devastation, to give those bodies laying in mass graves the respect and dignity they deserved.

Living in an era ravaged by death, he perhaps sought a way to deal with it, to get something from all that devastation, to give those bodies laying in mass graves the respect and dignity they deserved.

He described it as a "sanctuary of silence", and placed skulls damaged or disfigured by war and disease in prominent positions as a testament to those who had suffered.

And for the living? It's a message of absolute clarity and monumental force.

And for the living? It's a message of absolute clarity and monumental force.

In the 21st century we can hardly imagine such a thing being built, but what Tomášek created over eighteen long years was a monument to his own time - of its art, religion, and social conditions - and one that offers a striking window into the past.

Mentions

See All

Nicholas A. Christakis @NicholasAChristakis

·

Dec 23, 2022

This is a chandelier made of human bones. It’s from the middle of an incredible esoteric and informative thread illustrating why it would be so sad for twitter to die like MySpace or Friendster. So much to learn on this site from so many people expert in so many things.