Thread by Magnus Rasmussen

- Tweet

- Dec 11, 2022

- #PoliticalScience

Thread

After many years of hard work mine and @carlhknutsen "Reforming to Survive” is out with Cambridge University Press.

This is the one piece of research that I would rate the highest, combing qualitative and quantitative design in a single extensive study. Thread follows

This is the one piece of research that I would rate the highest, combing qualitative and quantitative design in a single extensive study. Thread follows

The short version of our book is that it presents a theoretical framework to understand how revolutionary fear should influence policymaking and provide the first systematic analysis of its influence on the massive expansion of labor regulations and social policies following 1917

You should be able to read it for free at the link below in a few days:

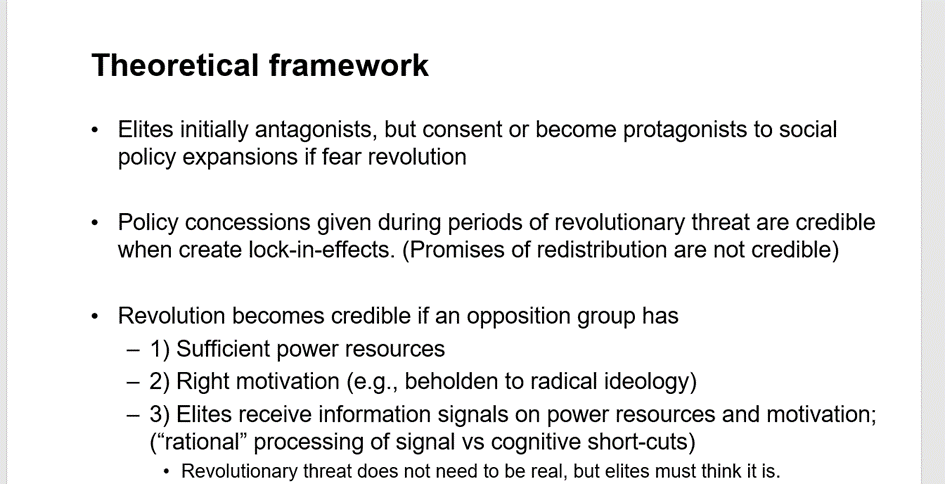

Our argument is centered on elites’ initial resistance to social reforms, which is attenuated during periods of increased revolutionary threat, with elites attempting to secure regime stability through political and social inclusion of workers.

What factors contributed to elites believing a worker orchestrated revolution was imminent and why did it appear that political and social co-optation could mitigate the revolutionary threat?

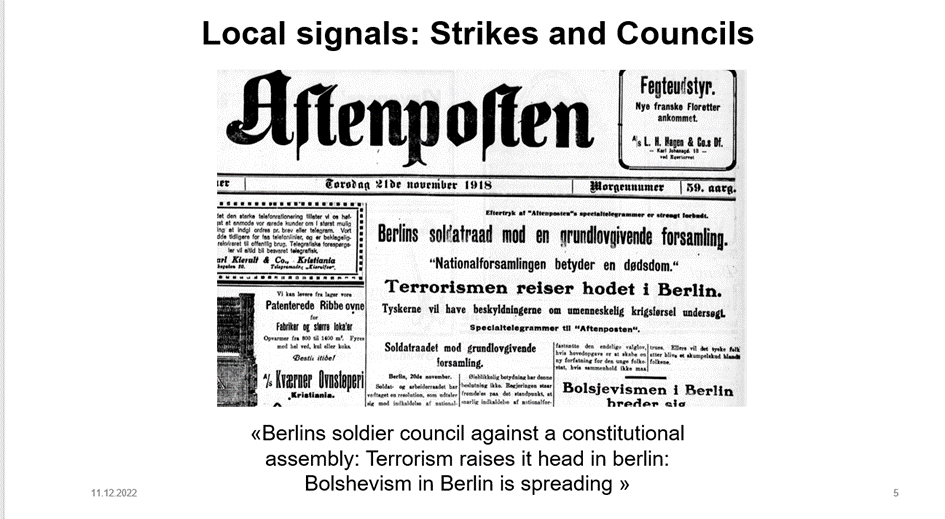

Starting with the first question, we argue there was both local and international “signals” that elites interpreted to mean that a revolution was likely.

First, the Bolshevik revolutions split European labor movements into revolutionary and reformists factions, distinguished by their acceptance of extra-parliamentary (revolution, strikes and protests) vs parliamentary road to power.

This led to formation of organizations such as Worker and Soldier councils which had played decisive role in the 1917 and 1918 revolutions, and elites interpreted these organizations through this lens.

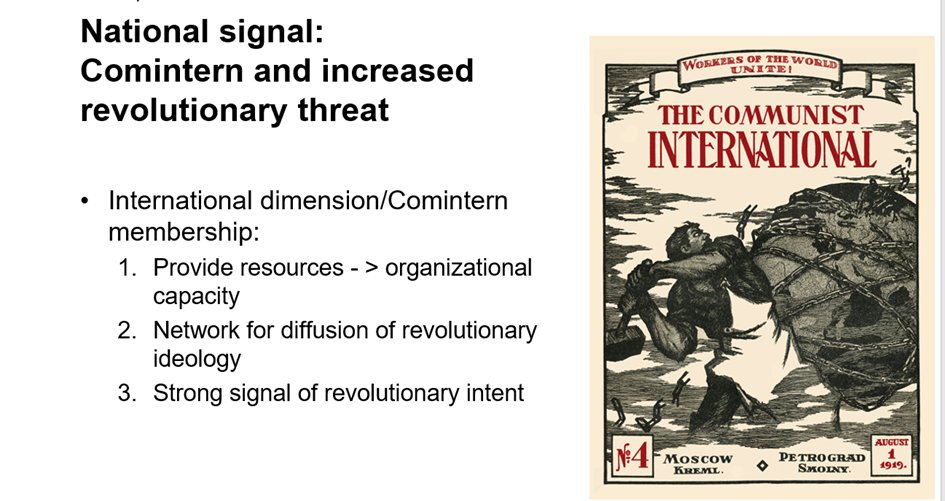

With the formation of the Comintern and worker parties affirming their allegiance to Moscow, elites received an even stronger signal of revolutionary intent and capacity.

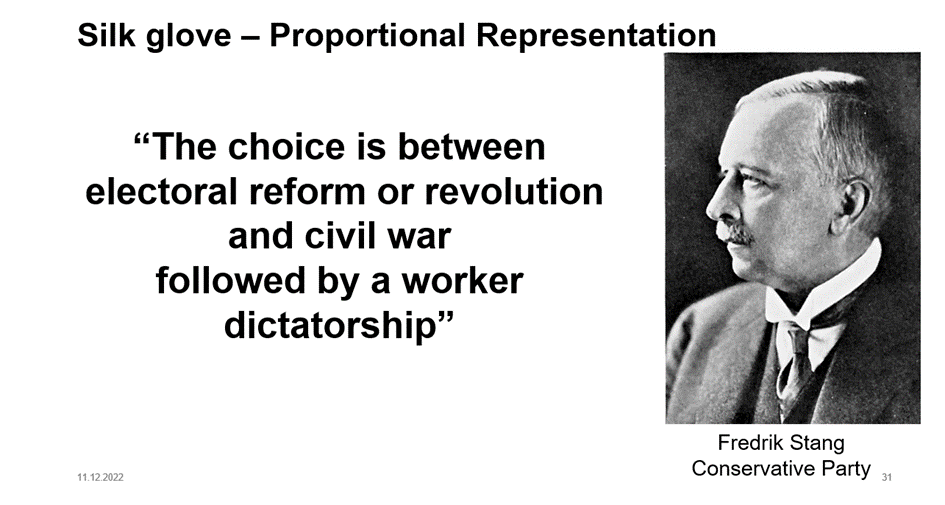

The internal power-struggle between these factions meant that elites decided to pursue a two-pronged strategy.

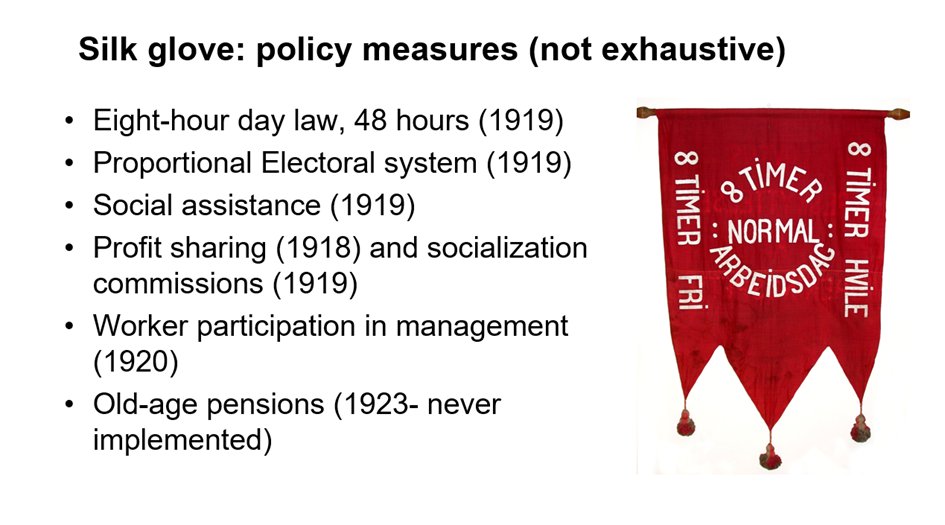

First a strategy of political and social reforms aimed at strengthening the reformist part of labor. This included electoral rule change and welfare measures.

First a strategy of political and social reforms aimed at strengthening the reformist part of labor. This included electoral rule change and welfare measures.

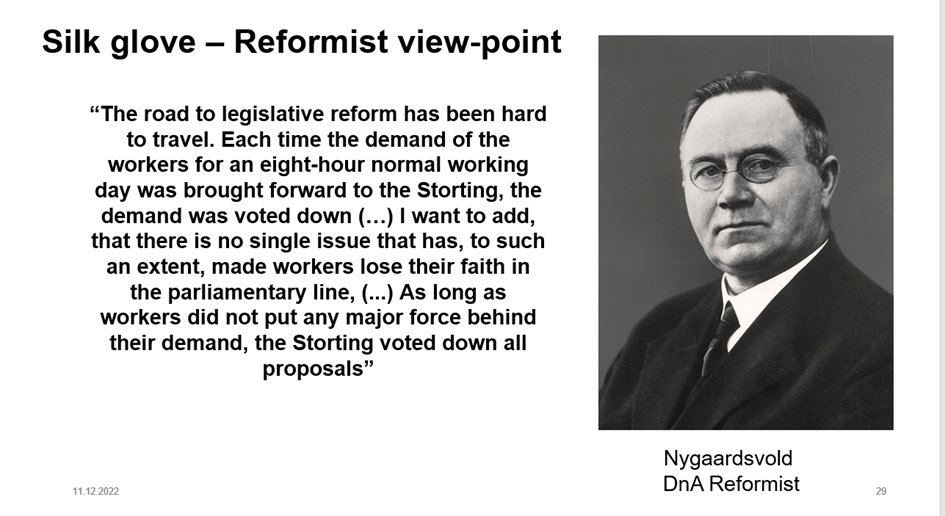

The reformists on their side saw that they could play up the revolutionary threat to gain concessions.

That elites could therefore come to over-estimate the true revolutionary threat of labor is not surprising, but to be expected.

That elites could therefore come to over-estimate the true revolutionary threat of labor is not surprising, but to be expected.

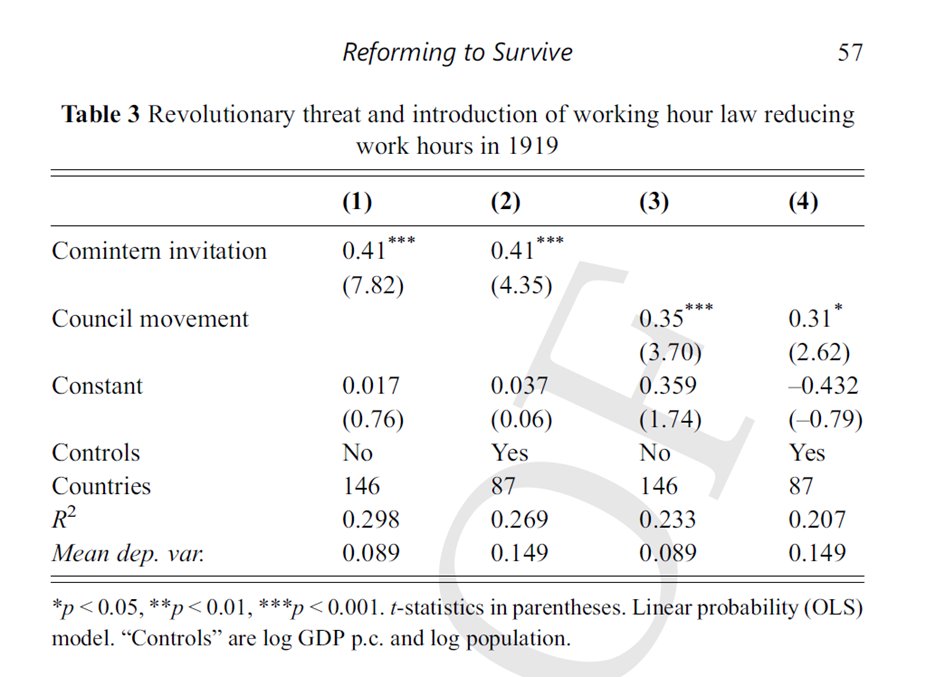

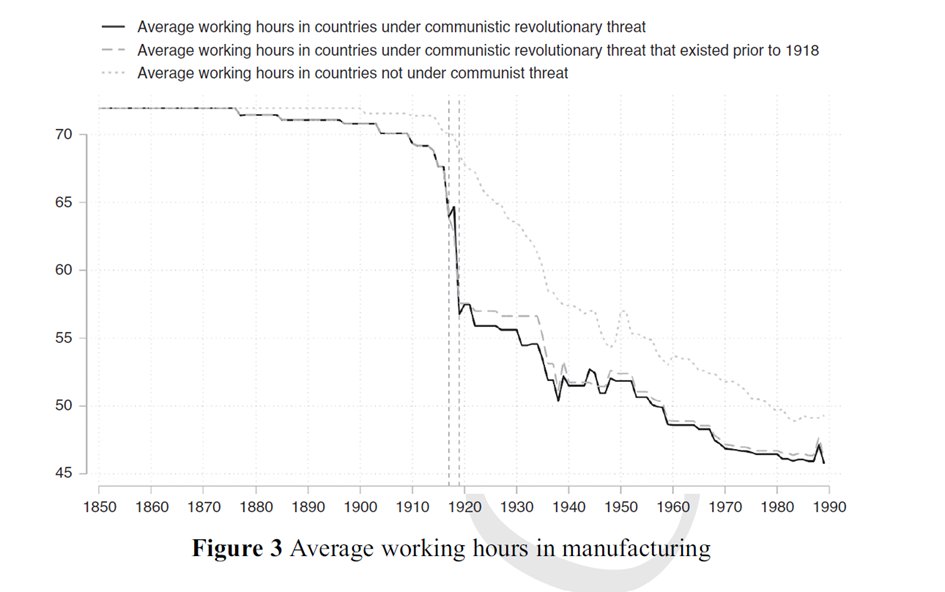

We find that measures of revolutionary fear, the radicalization of worker parties and the formation of worker and soldier councils, substantially drove social policy expansion around the world. Importantly, the shock persists until today (even if its importance has sig. subsided)

This was especially the case for the one piece of labor regulation that workers had demanded, but elites would not grant, the eight-hour day.

To do this, we used my datasets on working time regulation and social policy available for all here www.magnusbrasmussen.com/datasets

Our study tries to explain a worldwide phenomenon, but country-level data is too coarse and aggregated to provide direct evidence of the mechanisms in our theoretical framework.

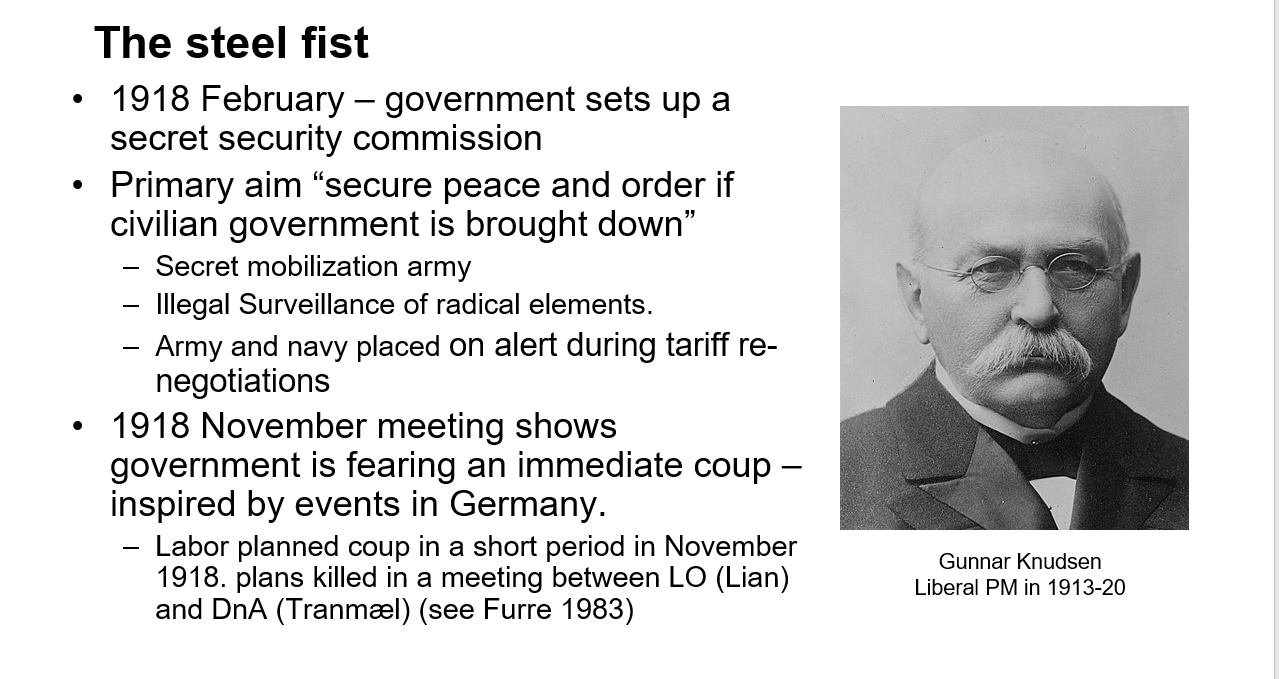

We therefore undertook a substantial case analysis of Norway between 1915-1925 to provide more direct evidence of linking revolutionary threat to elite motivations for social reform.

Our case-study included extensive archive work on party documents, parliamentary records, and consulting with major historical work.

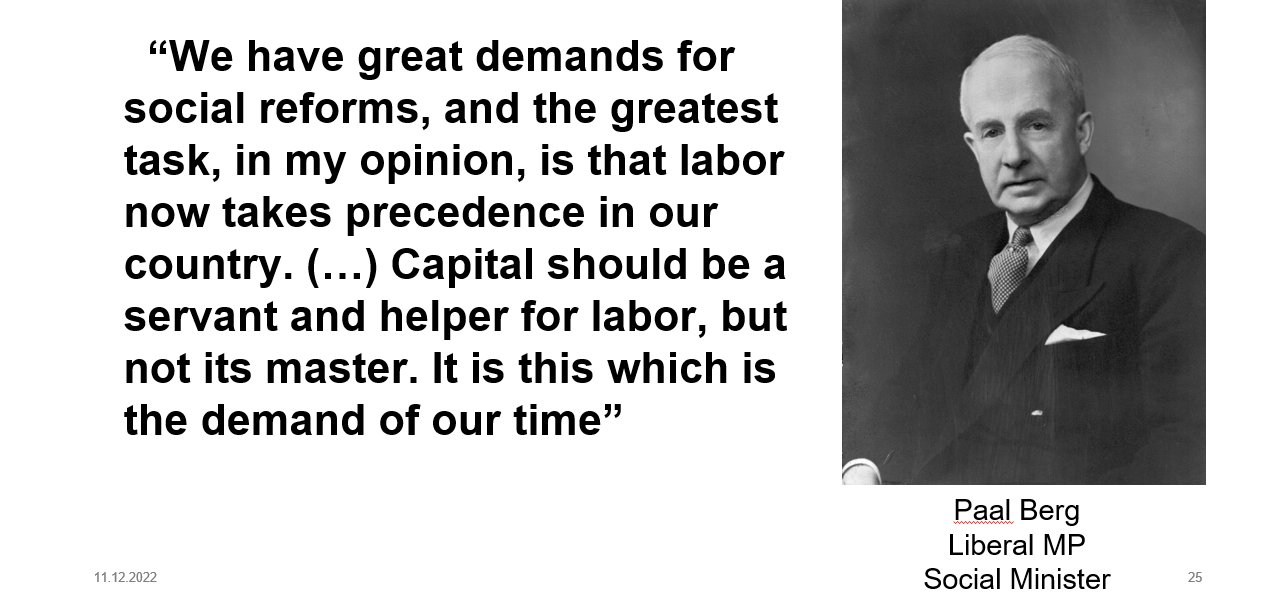

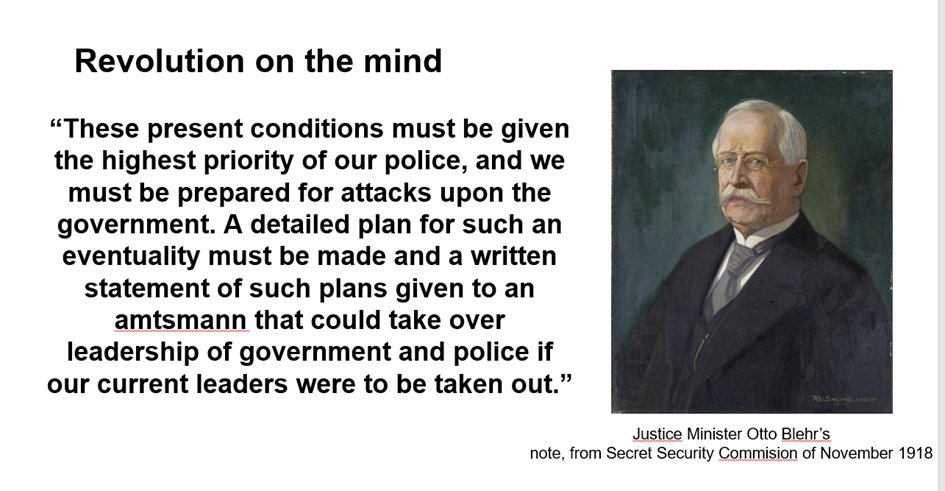

We also found clear evidence that both business elites and conservative and liberal politicians, which had previously resisted social reforms, came to accept social and political reforms as a necessity to reduce the perceived revolutionary threat.

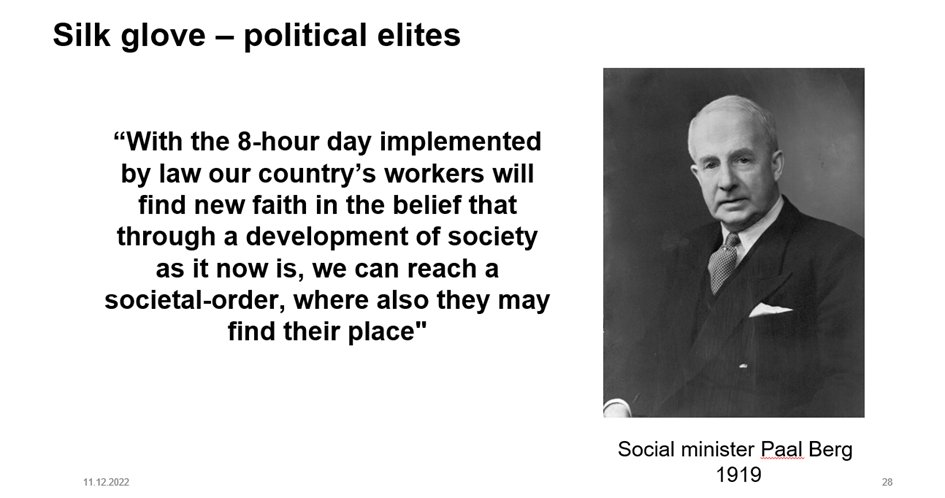

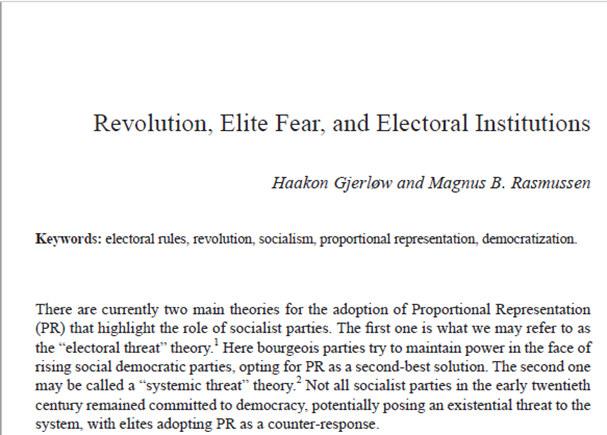

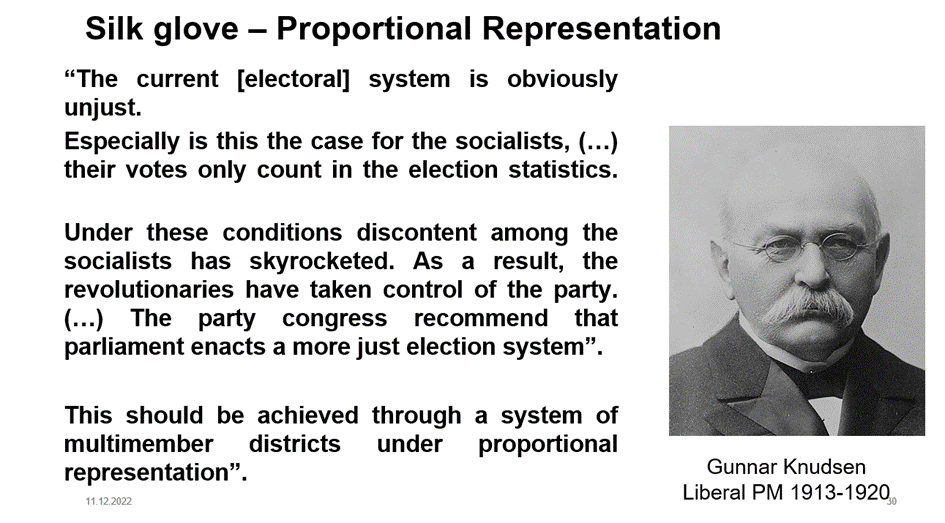

On political reforms, historians had previously linked the adoption of PR in 1919 to the increasing revolutionary threat posed by growing anti-parliamentary movement in the labor party.

The explanation was however theoretically underspecified and evidence was also somewhat lacking.

This part, however, turned out to be so bit that...

This part, however, turned out to be so bit that...

I together with @HaakonGjerlw ended up writing an independent paper using new dataset on industrial conflict and local soldier councils in Norwegian municipalities. It is now published in @Journal_CompPol

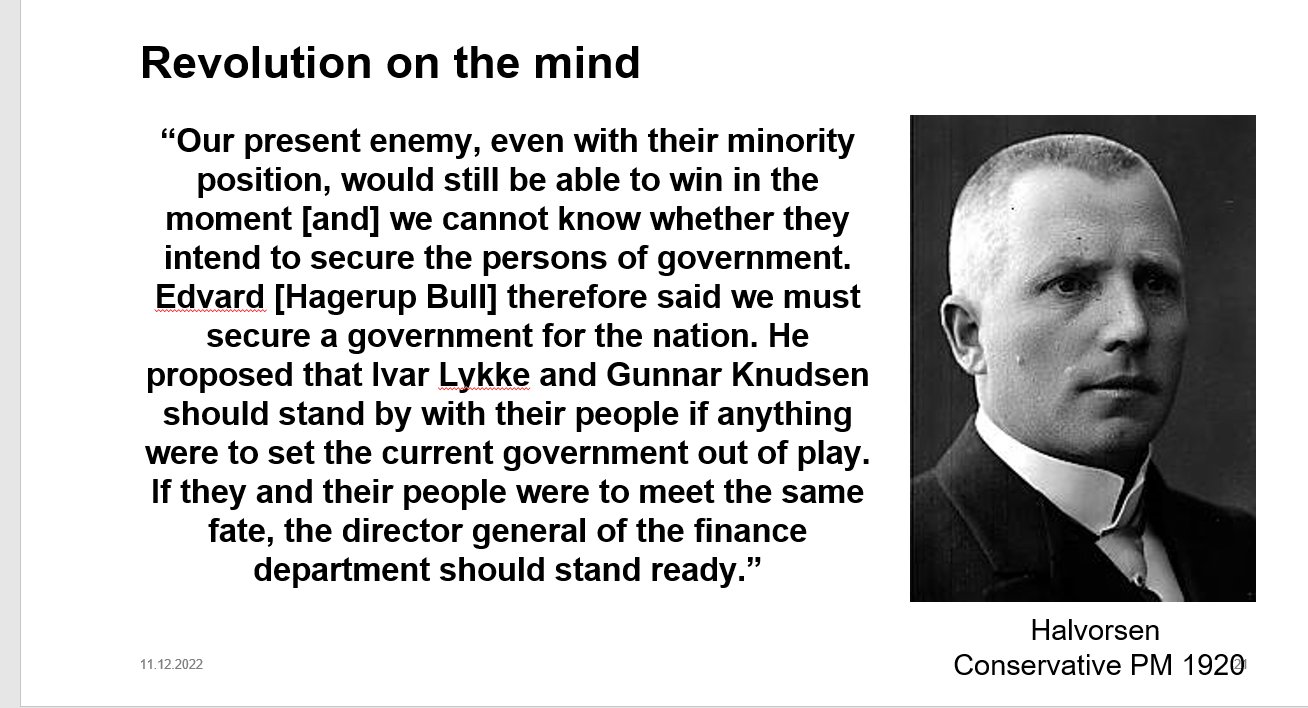

We find startling strong qualitative evidence that elites pursued a strategy of reformist inclusion to reduce support for the revolutionary wing.

From central actors spilling out our theory word for word...

From central actors spilling out our theory word for word...

The adoption of PR of course had impact on policymaking down the road. Increasing party cohesion (see paper by @JFiva cox and @ProfDanSmith ) and shifting coalition formation towards center-left governments in the long-term (Iversen & Soskice).

In the book we provide additional evidence for the presence of revolutionary threat on a host of issues, from socialization of all Norwegian firms to old-age pensions.

In sum, we argue that we have convincingly shown that the Bolshevik revolution had profound impact on policy and institutions outside of what would become the U.S.S.R.

How should we read our book in relation to the usual story presented in international studies on Norwegian welfare state development? How could revolutionary pressure end up playing a role in a country in which welfare state development is presented as a consensus project?

It’s important to recognize that Norway was a welfare state laggard. one of the last west-European countries to introduce old-age pensions and functioning unemployment regulation.

The reason for this backwardness was not that demands weren’t made for their implementation or government's didn’t attempt. The simple answer was that most welfare measures was downvoted by a combination of Conservatives, Rural liberals (farmers) and farmer party representatives

The pro-welfare coalition was simply too weak and the anti-welfare coalition too strong for any major breakthroughs to be achieved. (I also have a paper conditionally accepted for that will illustrate this more closely for working time regulations).

This meant that once especially Conservatives and some Liberals accepted the necessity of welfare reforms, major reforms could and would pass, but only as long as the revolutionary threat existed.

Together with @carlhknutsen I am planning to write short essay to bring out the policy-implications of our study more clearly. We will then touch on issues such as right-wing radicalism, environmental and green radicalism etc.

to finish this (LONG) thread, I want to highlight that no major work of social science is made in a vacuum, and this work certainly wasn’t!

For example, our book can of course be seen as a natural extension of the first paper that I and @carlhknutsen co-wrote journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0010414017710265

We have built on lots of previous research, including @AdamPrzeworski work on revolutionary threat and democratization, @WalterScheidel work on inequality and revolution, Kurt Weylands on elite responses to revolution, and @DrDaronAcemoglu & Robinson theoretical framework

We also benefited greatly for the framework developed by @isabelaanda to understand social policy reform in general and employer positions specifically. And Carina Schmitt and Herber Obinger on war and regime competition.

While our framework ends up being quite different from these authors, it would not have turned out as good without them

We are grateful for fantastic comments from several researchers, including but not restricted to @WalterScheidel, @HannaEBack, @AndrWalter15, @KlausPSDU, @tomas_paster, @sundellviz, @AndrejKokkonen, @LucasLeemann, @ferdinandeibl, @TinePaulsen, @cornell_agnes @torewig, @kotsadam,

@OSkorge, @SirianneD, @ferdinandeibl, @Scott__Gates @fr_jensenius @g_picot and @_alice_evans @NeilKetchley to mention a few of the many that have helped us!

We would also like to thank our editor, @stasavage. Without him this would have taken even longer and not been as good as it ended up being. When you are done reading our element, you should read his latest book.

Of course, we are massively indebted to several Norwegian historians, but these are unfortunately not on twitter. But just to mention a few, Nik Brandal, Nils Ivar Agøy, Aasmund Egge. Several of these also provided comments on the manuscript and made great comments and suggestion

We would also like to thank @pseudoerasmus for his twitter thread on a very early working paper version. The same goes to @BrankoMilan - we also benefited from his writings on capitalism and inequality.

Finally, on a more personal note, I would like to say that as a dyslectic there is something extraordinary about seeing your work in book format for the first time.

I hope all of you will love reading this element as much as I loved researching it. (End).