Thread

The widespread tendency to regard Russia’s autocratic regime as a somehow ‘postmodern’ phenomenon – a novel kind of illiberal governance that operates more through propaganda and political spin than coercion – has certainly been dealt a serious blow since February 24. (2/26)

Indiscriminate missile attacks and systematic state-mandated terror against Ukraine’s civilian population have revealed modern Russia’s essential brutality in a way that harks back to the worst excesses of the USSR.

Likewise, (3/26)

Likewise, (3/26)

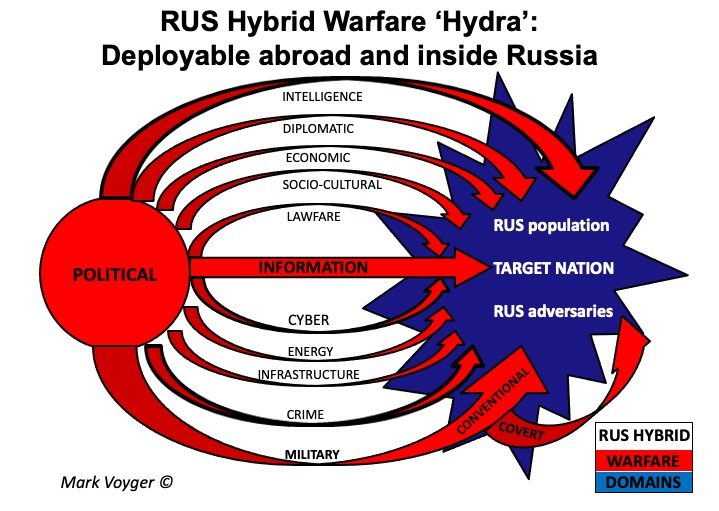

the well-known ‘hybrid’ theory of Russian warfare – emphasising its use of non-traditional capabilities from cyberattacks to weaponization of migrants and highlighting Russia’s preference for low-intensity grey zone conflicts to all-out war – has begun to ring hollow in (4/26)

light of what we are seeing in the battlefield: the most vicious conventional land war in Europe ever since World War II. For all the talk (over more than three decades) about how high-intensity territorial warfare is a thing of the past, (5/26)

it now seems to be back with vengeance.

But have all the previous arguments about the nature of Russian autocratic regime and its style of hybrid warfare been thereby invalidated? In fact, probably not. Both in terms of its regime character internally, (6/26)

But have all the previous arguments about the nature of Russian autocratic regime and its style of hybrid warfare been thereby invalidated? In fact, probably not. Both in terms of its regime character internally, (6/26)

and in how Russia behaves towards others, much in these analyses still holds water – even if most commentators were unable to foresee that in addition to doing all that, Russia would also launch a large-scale conventional war of aggression.

In fact, (7/26)

In fact, (7/26)

it might be more useful to say that what Russia is currently doing is waging two different wars at once: one kinetic war against Ukraine, and another, hybrid war against the West. While the two are intertwined in a multitude of ways, (8/26)

and hybrid methods are obviously also used against Ukraine, it makes sense to keep the two analytically separate.

Elsewhere, I have argued against the notion that the West is somehow a party to Russia’s war against Ukraine, and I stand by it.

(9/26)

Elsewhere, I have argued against the notion that the West is somehow a party to Russia’s war against Ukraine, and I stand by it.

(9/26)

The West is a non-belligerent supporter to Ukraine, but as long as there are no NATO boots on the ground in Ukraine, it is not a belligerent itself. When the victory arrives, it will belong to Ukraine alone. (10/26)

Ascribing the West an oversized role in this war amounts to a repetition of Russian propaganda that for a variety of reasons would like to erase Ukrainian agency and depict the conflict as being somehow only between Russia and the West.

But conversely, (11/26)

But conversely, (11/26)

we need to be careful to not to ascribe Ukraine an oversized role in Russia’s hybrid war against the West.

The latter did not start only in 2022 or even 2014. It has been going on for a long time, and it pre-dates Western political and military assistance to Ukraine. (12/26)

The latter did not start only in 2022 or even 2014. It has been going on for a long time, and it pre-dates Western political and military assistance to Ukraine. (12/26)

Furthermore, it would doubtlessly still continue even if the West lifted all its sanctions on Russia and immediately ceased its assistance to Ukraine. (13/26)

Appeasers advocating ceding Ukrainian territory and lives in hope of making Russia stop its aggressive behaviour (either as a supplier of energy or in some other capacity) are either very naïve or arguing in bad faith.

(14/26)

(14/26)

The Baltics, for example, have more than three decades of experience of being targeted by Russian propaganda trying to hurt their international reputation by catering to and reinforcing Western prejudices and stereotypes.

For equally as long, (15/26)

For equally as long, (15/26)

they have seen Russia trying to meddle in their internal affairs and sow division between the ethnic groups by attempting to manipulate their Russian-speaking minorities. (16/26)

The energy weapon – arbitrary cuts to agreed energy supplies on a variety of pretexts – has been in use against the Baltics since the 1990s. (17/26)

The 2007 massive cyberattacks against Estonia that followed the Estonian government’s decision to move a monument to Soviet ‘liberators’ from downtown Tallinn to a military cemetery close nearby are eerily reminiscent of similar events just a few weeks ago. (18/26)

But of course, Russian hybrid warfare has not been targeting only the Baltics. Russian meddling in Western elections, most famously in the 2016 US presidential elections, is internationally well-known. (19/26)

The same holds true about Russia’s strong degree of support for far right and far left political forces in Europe and the US, attempting to exploit divisions in Western societies and undermine the resilience of their democracies. (20/26)

Russia’s intelligence agencies have carried out plenty of ‘special operations’ outside of its borders, from poisonings to sabotage. All of this continues still today.

Nevertheless, even though Russia’s two wars are separate, (21/26)

Nevertheless, even though Russia’s two wars are separate, (21/26)

the course of Russia’s hybrid war against the West can be and is directly influenced by Russia’s war against Ukraine. Over the last seven months, we have seen that whenever Russia is experiencing setbacks in the battlefield, (22/26)

it tries to compensate by hitting back at the West with hybrid weapons meant to discourage further sanctions on Russia or further assistance to Ukraine, and to encourage lifting of the sanctions that already exist. (23/26)

Showing resilience in face of such tactics is as important as anything else that the West is currently doing to help Ukraine.

At the same time, Russia’s war against Ukraine is a distraction for Russia. It ties up its resources and capabilities, (24/26)

At the same time, Russia’s war against Ukraine is a distraction for Russia. It ties up its resources and capabilities, (24/26)

and creates more awareness in the West about the nature and goals of Russian hybrid warfare. The more successful Ukraine is in resisting Russian aggression, the less well Russia is able to wage its other war against the West. (25/26)

Fully supporting Ukrainian victory in the battlefield thus remains the rational method by which the West can win its own struggle against Russian hybrid aggression.

END.

(26/26)

END.

(26/26)

Mentions

See All

Jason Scott Montoya @JasonSMontoya

·

Dec 4, 2022

- Curated in Russia Invades Ukraine

Jason Scott Montoya @JasonSMontoya

·

Dec 12, 2022

- Curated in Russia's Deception Machine