Thread

Second Chechen War – a cautionary tale on why Russia should not be trusted, especially Putin’s Russia. Don't ask Ukraine to settle

In August of 1996, the Chechens achieved the unthinkable. They won a war against the Russians securing their independence. Kind of.

In August of 1996, the Chechens achieved the unthinkable. They won a war against the Russians securing their independence. Kind of.

Though the Russian troops pulled out of Chechnya, the Kremlin still did not recognize Chechen independence. However, as the 1996 ceasefire agreement was to expire in 2001, back then it seemed like there was enough time to sort out the details.

And indeed, things were off to a good start. The first war, which took up to 100,000 lives was over. Aslan Maskhadov was elected president of Chechnya, after a short rule of Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev as acting president following the assassination of Dzhokhar Dudayev.

In May of 1997 Maskhadov signed a formal peace treaty with the Russian president, Boris Yeltsin. However, that’s where the good things ended. The first Chechen War left the country in ruins.

The Chechen economy was devastated and their access to the world was limited by the Russian blockade. Some of those who fought in the war decided not to lay down their arms and turned to a life of crime.

Kidnappings for ransom or slavery became a viable source of income in the country. Many of the foreign volunteers from the Middle East and Afghanistan who answered the First War’s call to Jihad remained in the country after the war.

The continued funding from the Middle East maintained pressure on the Caspian oil field operations by disrupting oil pipelines going through Chechnya. And with the influx of foreign money, the radicalization of the impoverished local population remained as well.

The funding also empowered Chechen warlords with more radical inclinations. The ranks of their private militias swelled and their aspirations for power grew. Maskhadov’s secular government’s grip over the country started to loosen, culminating in armed clashes between...

...Chechen government forces and the radicals in Gudermes, at the time the country’s second-largest city. Vice-president Arsanov and prime-minister Basayev urged president Maskhadov to show some leniency.

Maskhadov feared that the situation could unravel into a full-blown civil war and leave the country vulnerable to another Russian invasion. And in February of 1999 Sharia law was introduced in Chechnya to appease the radical opposition.

The situation in Russia was not all that rosy either. The Russian economy continued to stumble in the new, unknown realms of capitalism. The First Chechen War directly contributed to the economic strains of the country.

By the end of the conflict, it is estimated that the first war in Chechnya cost Russia nearly $5.5 billion or 1.4% of its annual GDP. The 1997 Asian financial crisis and tumbling oil prices were the final straw that broke the camel’s back. www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/chechnya/chechen-war-in-the-context-of-contemporary-russian-politics...

In the summer of 1998, Russia defaulted on its debt and devalued its national currency, making its population even poorer. The situation was serious. Yeltsin had to cancel his summer vacation and go back to Moscow, where he was expected to reshuffle his Cabinet.

But the only change he made was appointing a new head of the Federal Security Service, Vladimir Putin. The faltering economy did no favors to Yeltsin’s public approval ratings.

The collapse of the USSR left many people fending for themselves in the new Russia, something they were not used to as for decades the state decided for them how they’d make their living. In the new Russia, many failed to find a legal way to earn.

Some prospered, becoming powerful oligarchs. Most lived from paycheck to no paycheck. The new economic divide left many disenfranchised with the democratic process, which partially explains the current state of Russia.

Adrian Campbell does a great job analyzing how the 1990s shaped today’s Russia. As the economy continued to stumble Yeltsin started to lose support in the government as well. In May of 1999, the Russian State Duma attempted and failed to impeach Yeltsin.

theconversation.com/the-wild-decade-how-the-1990s-laid-the-foundations-for-vladimir-putins-russia-141...

theconversation.com/the-wild-decade-how-the-1990s-laid-the-foundations-for-vladimir-putins-russia-141...

The first war in Chechnya was one of the five impeachment charges and obtained the highest number of votes, but failed to hit the required amount for impeachment. Later in August Yeltsin appointed Putin, one of his loyalists, as the new prime minister.

After handing over the reins to his successor-to-be, Yeltsin had largely disappeared from the political scene for the rest of the year.

In the meantime, over the three-year gap between the First and Second Chechen Wars, the two sides failed to improve their relations.

In the meantime, over the three-year gap between the First and Second Chechen Wars, the two sides failed to improve their relations.

In fact, the opposite happened. Border clashes and armed raids into the Russian territory were frequently conducted by Chechen militias, allegedly led by radical leaders who also clashed with Maskhadov’s government.

In March of 1999, Moscow sent an envoy Gennady Shpigun, a general with the Ministry of Internal Affairs. He, however, promptly disappeared upon arriving in Grozny, presumably kidnapped, and killed.

His disappearance led to the first calls among the Russian ministers for a new invasion into Chechnya (e.g. Minister of Internal Affairs Stepashin). The first disastrous war was still fresh in memory and the Russian public would need some convincing.

Moreover, a new invasion without a legitimate trigger was against the terms of the 1997 peace treaty. However, the motives for the first war in Chechnya were still valid. The Russian federal government still wanted to control the oil pipelines and oil fields in Chechnya.

They also wanted to make an example out of the rebellious republic to suppress any similar sentiment among other autonomies.

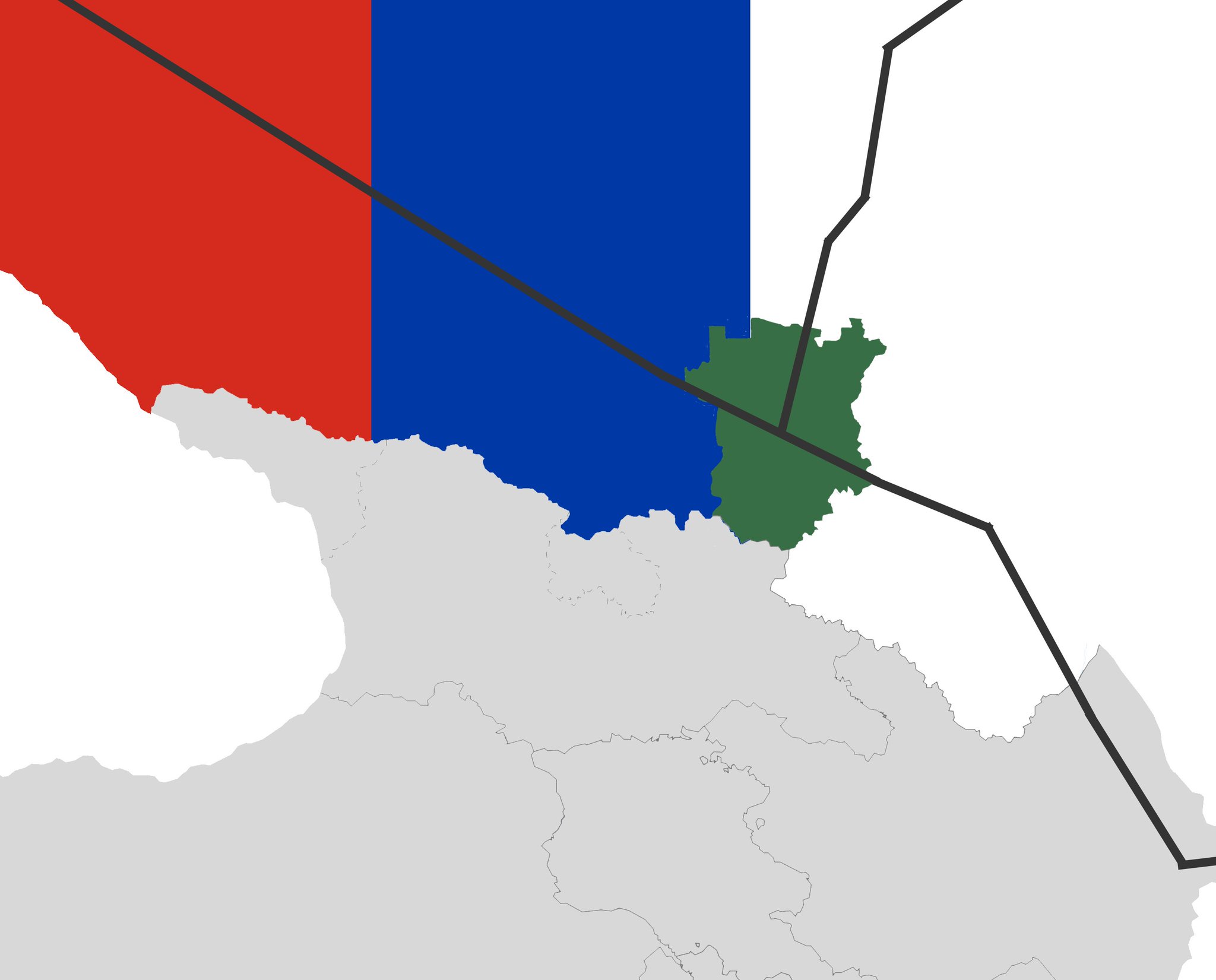

On August 7, 1999, another incursion from Chechnya into Dagestan, an autonomous republic in Russia, commenced.

On August 7, 1999, another incursion from Chechnya into Dagestan, an autonomous republic in Russia, commenced.

However, it was unlike any of the previous attacks. It was the largest incursion yet with up to 2,000 militants crossing the border under the leadership of Shamil Basayev and Ibn Al-Khattab, a Saudi-born warlord. A couple of weeks later their numbers grew to 10,000.

The radical warlords were hoping to oust the federal government in Dagestan. The federal response was quick, and the militants were pushed back into Chechnya in mere five weeks. The War in Dagestan was a minor conflict and in the eyes of the public, it was just another incursion.

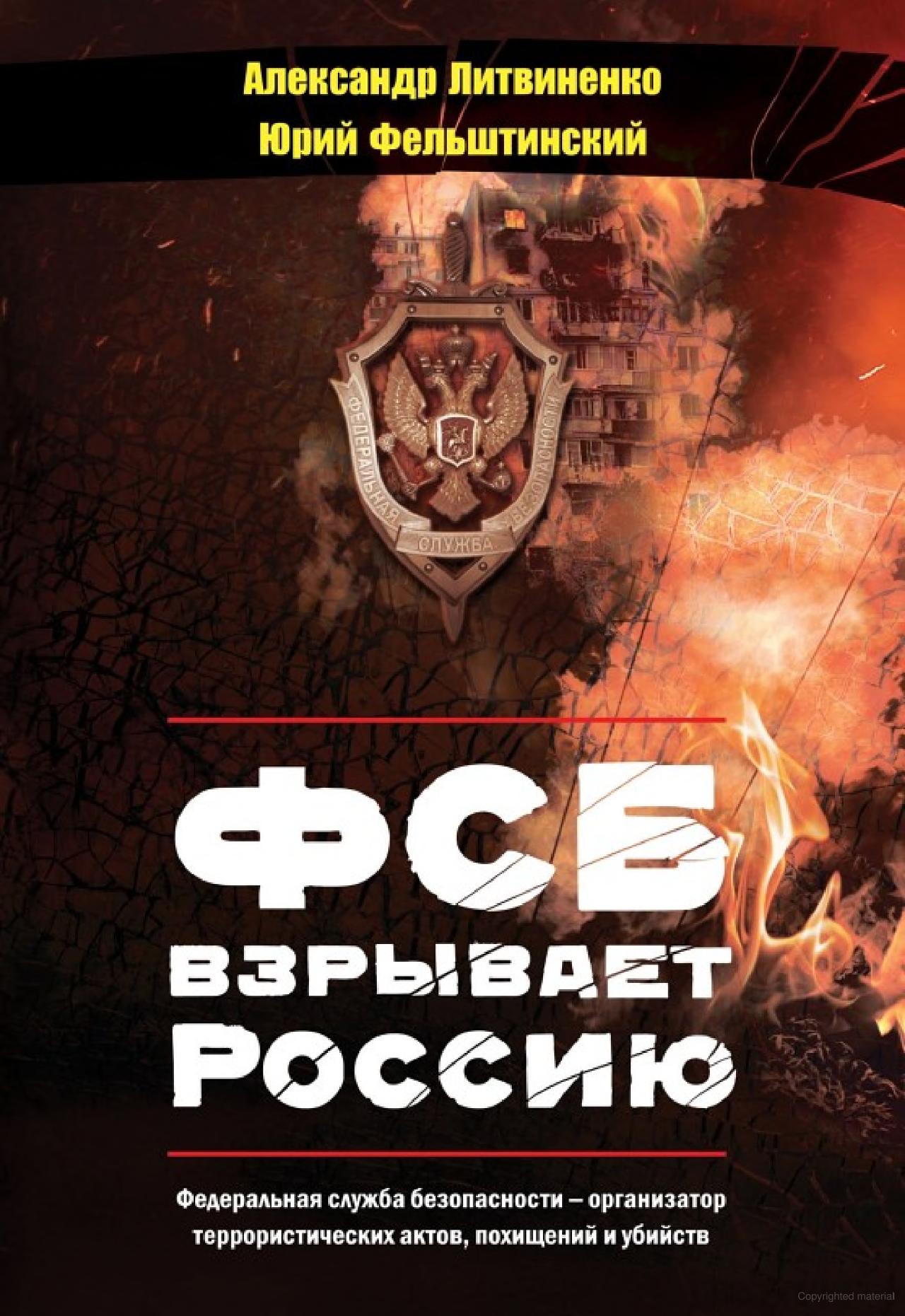

In their book, “Blowing Up Russia,” Alexander Litvinenko and Yury Feltishinsky refer to an investigation by Versiya claiming that the invasion of Dagestan was orchestrated by Moscow and Basayev made a deal with Moscow.

Ichkeria’s exiled foreign minister Akhmadov dismissed the claims. While in exile Russian oligarch Boris Berezovsky claimed that Basayev had an agreement with Putin to invade Dagestan to provoke a Russian invasion in exchange for the presidency of Ichkeria.

However, the Russian public still needed a bit more “convincing.” A series of apartment bombings in Russia took place just as the war in Dagestan was wrapping up. In the first half of September 1999 in the cities of Buynaksk, Moscow, and Volgodonsk more than 300 were killed...

...in a series of terrorist attacks spreading a wave of fear. The responsibility was quickly pinned on the Chechen separatists and President Maskhadov. Prime minister Putin vowed to quickly bring those responsible to justice.

And on September 23rd, 1999 Putin ordered the air bombing of Grozny. The real perpetrators of the apartment bombings were never conclusively identified. Litvinenko and Politkovskaya worked on an independent investigation and their preliminary finding pointed toward the FSB.

Both were assassinated in 2006. “Ryazan sugar” incident supports that claim. At any rate, the terrified Russian public was now in support of the Second Chechen War. Much like the first war, the Second Chechen War started with an air bombing campaign of Chechnya.

Unlike in the first war, the bombing campaign was much larger in scale. This time the Russians were not only using more conventional bombs, but also thermobaric bombs and tactical ballistic missiles.

During the opening two weeks of the air campaign, an estimated 16000 tons of munitions were dropped on Grozny, an intensity that is only comparable to the WW2 level of destruction.

Putin was not going to repeat the mistakes of the first war, and all of Chechnya had to be softened up significantly before the ground forces were to roll in. Putin also got something Yeltsin did not have in the first war. He gained Chechen allies.

Akhmad Kadyrov, Chechnya’s chief mufti, the man who called for Jihad in the first war, switched sides. Many still argue about the motivation behind his decision. Some say that he was against the radical version of Islam preached to the Chechen people by foreign volunteers.

Some claim that he was disillusioned by the failures of the somewhat independent Chechen state. Others claim that he was tempted by the promises of power and was outright bribed by the Kremlin.

Whatever, the claims may be, Kadyrov, those close to him, and his private militia were now on the Russian side. Soon, three other prominent Chechen warlords, the Yamadaev brothers, followed suit.

On October 1st, the Russian Ground forces commenced their land invasion. Unlike in the first war, the ground forces were not completely comprised of conscripts. A significant proportion of them were enlisted volunteers.

On October 10 Maskhadov attempted to negotiate for peace with the Russian side promising a crackdown on the radical warlords. His offer was promptly dismissed.

The continued bombing of Chechnya and the newly loyal Chechen warlords allowed the Russian forces to reach the outskirts of Grozny by December 1st. There was no armored rush like in the first battle of Grozny of 1994.

The Russians took their time to bomb the city with any type of artillery they had at their disposal, including some exotic kinds. As the battle of Grozny raged, something unexpected happened.

In the new year’s address to the nation, Yeltsin resigned, leaving Putin as acting president of the Russian Federation. By the end of January 2000, the Chechen defenders realized that their position in the city had become untenable.

In the first week of February during a winter storm, they attempted a breakout. 4,000 Chechen fighters and several hundred civilians tried to use the weather to cover their retreat. They still were ambushed by the sieging federal forces.

The exact number of survivors is not known, but those who escaped took to the mountains. Shortly after, the federal forces moved in and claimed the carcass of the city.

The overarching theme of the war is the non-exact number of casualties taken by either side, but it is estimated that up to 8,000 civilians were killed in this battle of Grozny. As the war shifted into the mountains, airstrikes and shelling continued.

Ambush tactics successful in the first war were yet again employed by the Chechen separatists. However, with many Chechens now fighting on the Russian side and the intensity of shelling and bombing, it was clear that the war of attrition could not be won by the separatists.

The Russian public was impressed by Putin’s war success and his response to the apartment bombings and on March 26, 2000, he secured his first presidential term. On May 31 the federal government declared the end of major combat operations.

Akhmad Kadyrov was appointed leader of the new Chechen government, the pro-Moscow Chechen government. He ruled with an iron grip cracking down on separatists and opposition alike. However, his rule was not long. In May 2004 an explosion ripped through a stadium in Grozny.

Akhmad Kadyrov, was one of the victims, leaving his son, Ramzan, as a de facto ruler of Chechnya. However, the war was far from over. Terror tactics were thrown into the mix of asymmetric warfare in 2000.

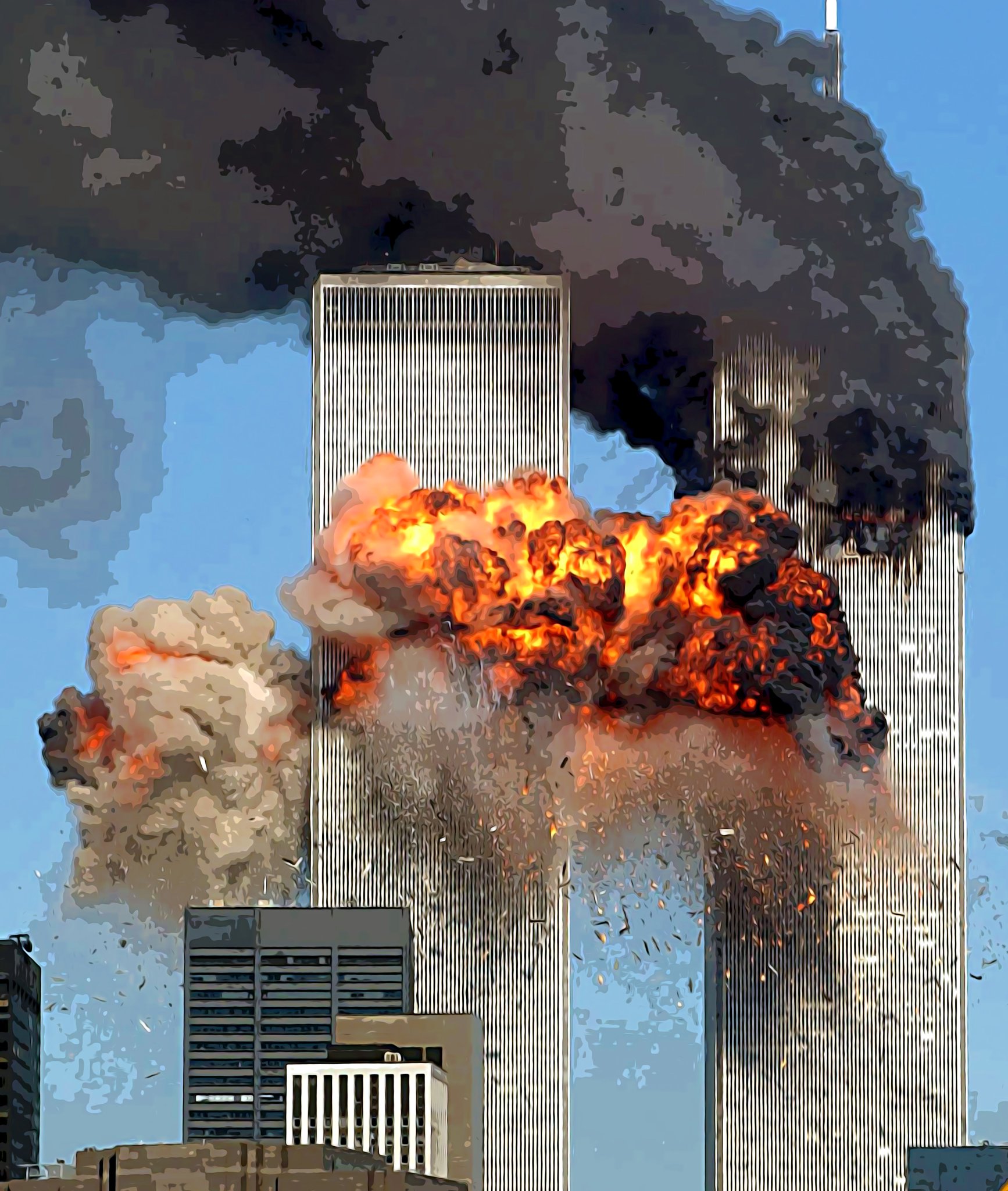

On July 2 suicide bombers were first employed in a series of attacks on Russian military positions in Chechnya. Many other terrorist attacks followed over the years of the insurgency phase. And after the 9/11 attacks, Putin justified the war in Chechnya as Russia’s war on terror.

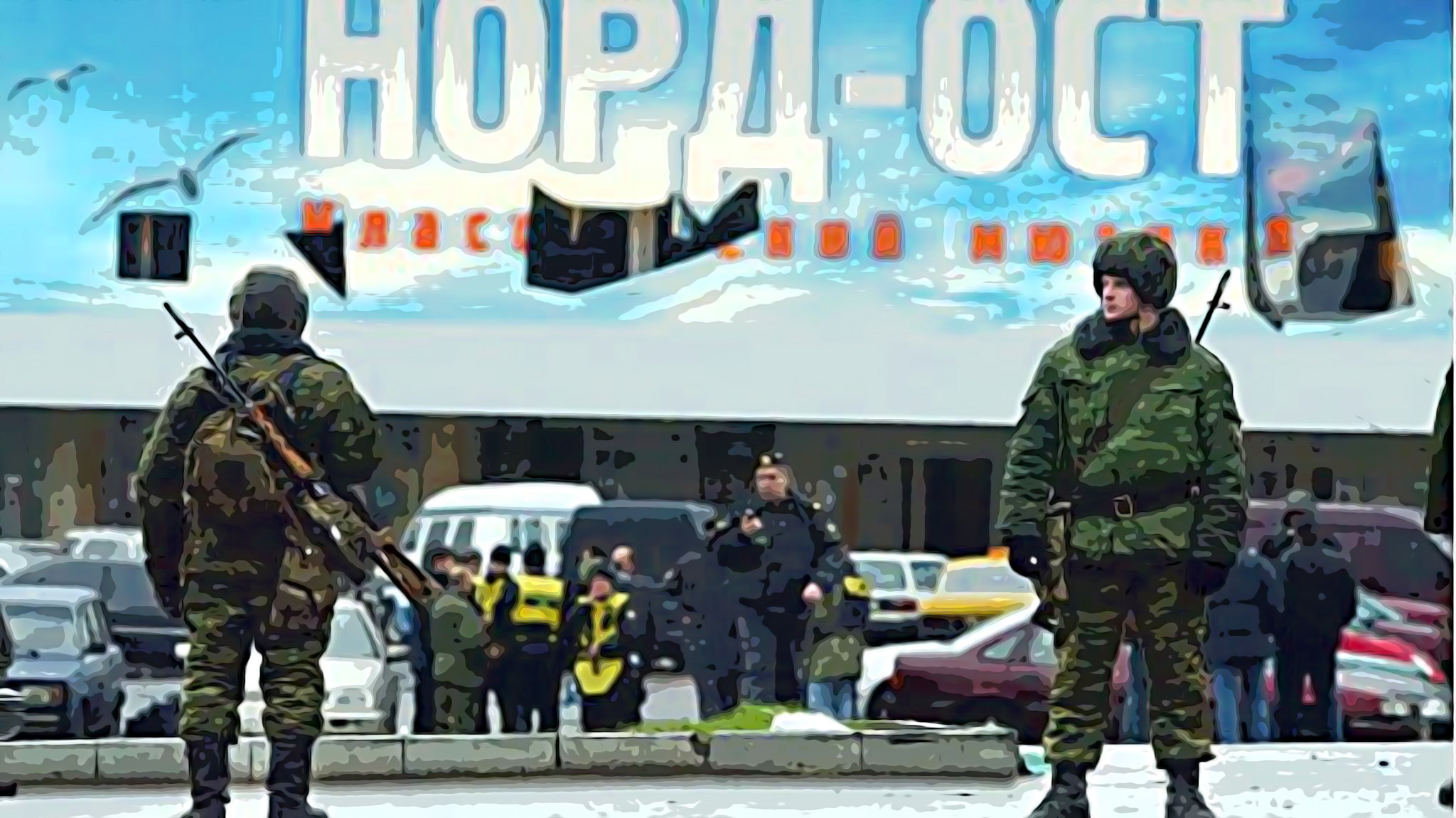

But perhaps some of the grimmest episodes of the war in the eyes of the public came in 2002 and 2004. Hoping to repeat the success of the Budyonnovsk hospital hostage crisis of 1995, Basayev organized an attack on a theater in Moscow on October 23, 2002.

40 attackers took 916 civilians hostage. Their demands included independence for Chechnya and an immediate withdrawal of the federal troops. Three days later a potent nerve gas was pumped into the building knocking out most and killing many in the building.

The Russian special forces stormed the building afterward, killing all hostage-takers. With more than 130 civilians killed, the Russian government claimed the counter-terror operation was a success. Basayev would try again in 2004.

On September 1, 2004, 32 attackers took hostage more than 1000 civilians, mostly children, in a school in Beslan, a town in North Ossetia. Again, the hostage-takers demanded independence for Chechnya. But two days later the federal troops stormed the school.

All but one perpetrator were killed. 312 civilians lost their lives as well, including 186 children. Maskhadov condemned the attacks in Beslan and pleaded with Basayev to stop the attacks.

In early 2005 Maskhadov declared a unilateral ceasefire asking all separatist factions to stand down, but he was killed by the FSB later the same year. With his death, the separatist government of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria effectively ended.

Basayev died the followed year in an explosive mishandling incident, though the FSB initially claimed credit. Though many Chechen warlords remained active, none were as powerful and influential as Basayev.

With each warlord assassinated or killed in action, the separatist movement gradually died out. The insurgency phase ended in 2017 with Chechnya becoming a federal subject of Russia.

Often the scale of conflicts is measured in human lives.

Often the scale of conflicts is measured in human lives.

Anywhere between 50,000 to 200,000 people were killed in the Second Chechen War. But this war was not a conventional conflict. It seems we will never know the full extent of the war crimes committed during the war.

Both Russia and the pro-Kremlin Chechen government are keen on moving forward and letting the past be past. After all, in the true highlander fashion, Ramzan Kadyrov is the only one left standing in Chechnya.

Separatists and radical leaders were all killed, the pro-Russian Yamadayev brothers were assassinated over the years. Ramzan has no real contenders left in Chechnya and he wields his absolute power in Chechnya absolutely.

There are numerous sources indicating that human rights violations in Chechnya are more egregious than in Russia itself. But while he is allowed to remain in power and there is money to be made from oil, Ramzan remains loyal to the Kremlin.

The federal government invested heavily in the reconstruction of Grozny and the modern capital of Chechnya looks nothing like the ruins of the early aughts. The prominent mosque in the center of the city serves as a reminder that it is still Chechnya.

Every year Ramzan parades his private militia not only to show the Kremlin that he is in full control of the region but to also subtly caution Putin that peace costs money. But it doesn’t mean that the war in Chechnya was an exercise in futility for Putin.

In fact, the victory in Chechnya fueled Putin’s political success. It is through this war he learned that large swathes of the Russian population won’t care much about their economic struggles if their patriotic desires for military success are satisfied.

Mentions

See All

Jason Scott Montoya @JasonSMontoya

·

Dec 12, 2022

- Curated in Chechnya & Russia