Thread

Rebirth of Russian Colonialism - First Chechen War

The collapse of the USSR in 1991 marked the end of the Cold War. Few empires disintegrate peacefully and this time was no exception. Regional conflicts broke out but none were as bloody and destructive as the First Chechen War.

The collapse of the USSR in 1991 marked the end of the Cold War. Few empires disintegrate peacefully and this time was no exception. Regional conflicts broke out but none were as bloody and destructive as the First Chechen War.

To understand the causes of the Not-So-First First Chechen War we need to look back a few centuries. The history of Chechnya and the rest of the Northern Caucasus is as complex as the ethnic composition of the region.

In the middle ages, the region saw empires come and go. The Khazars, the Mongols, the Timurids. The Chechens distinguished themselves as one of the few peoples who managed to successfully defend against the Mongol invasions.

However, it nearly destroyed their state and contributed to the rise of a decentralized clan-based martial society. Even to this day division by Taip or client exists among the Chechens. In the 16th century, the Ottomans and Persians started clashing for control over the region.

Around the same time, the Russians started attempting to establish settlements. Mountainous terrain and resistance of the local population made expansion difficult for everyone.

Nonetheless, the strategic importance of having a natural barrier with the Ottoman empire kept the Russians trying, especially considering how many times the Russians and the Ottomans fought each other over the centuries.

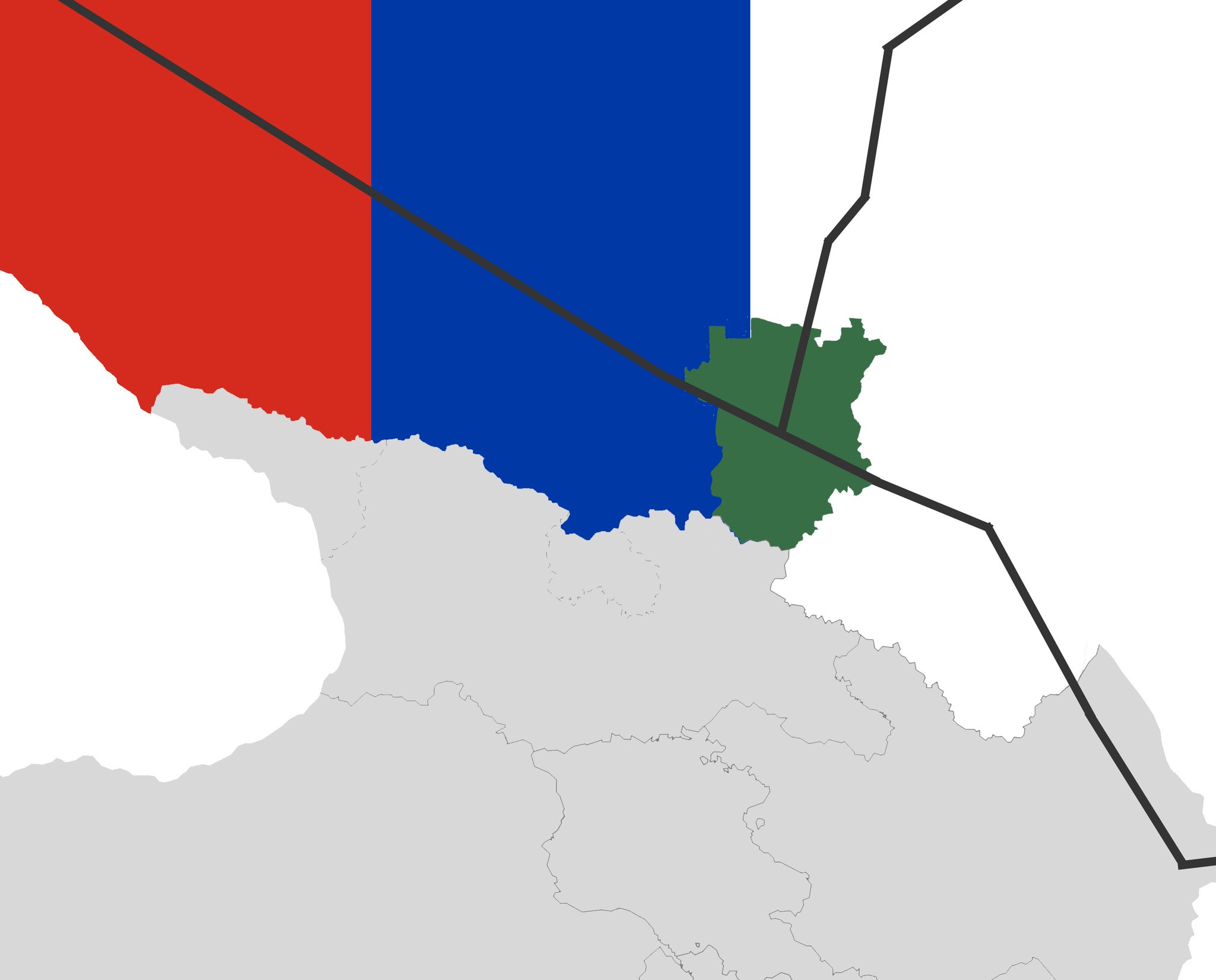

With the incorporation of eastern Georgia in Transcaucasia in 1800 into the Empire, the Russians were ready to properly invade the Northern Caucasus. Any serious attempts had to be delayed though due to the baguette wars in Europe of the early 19th century.

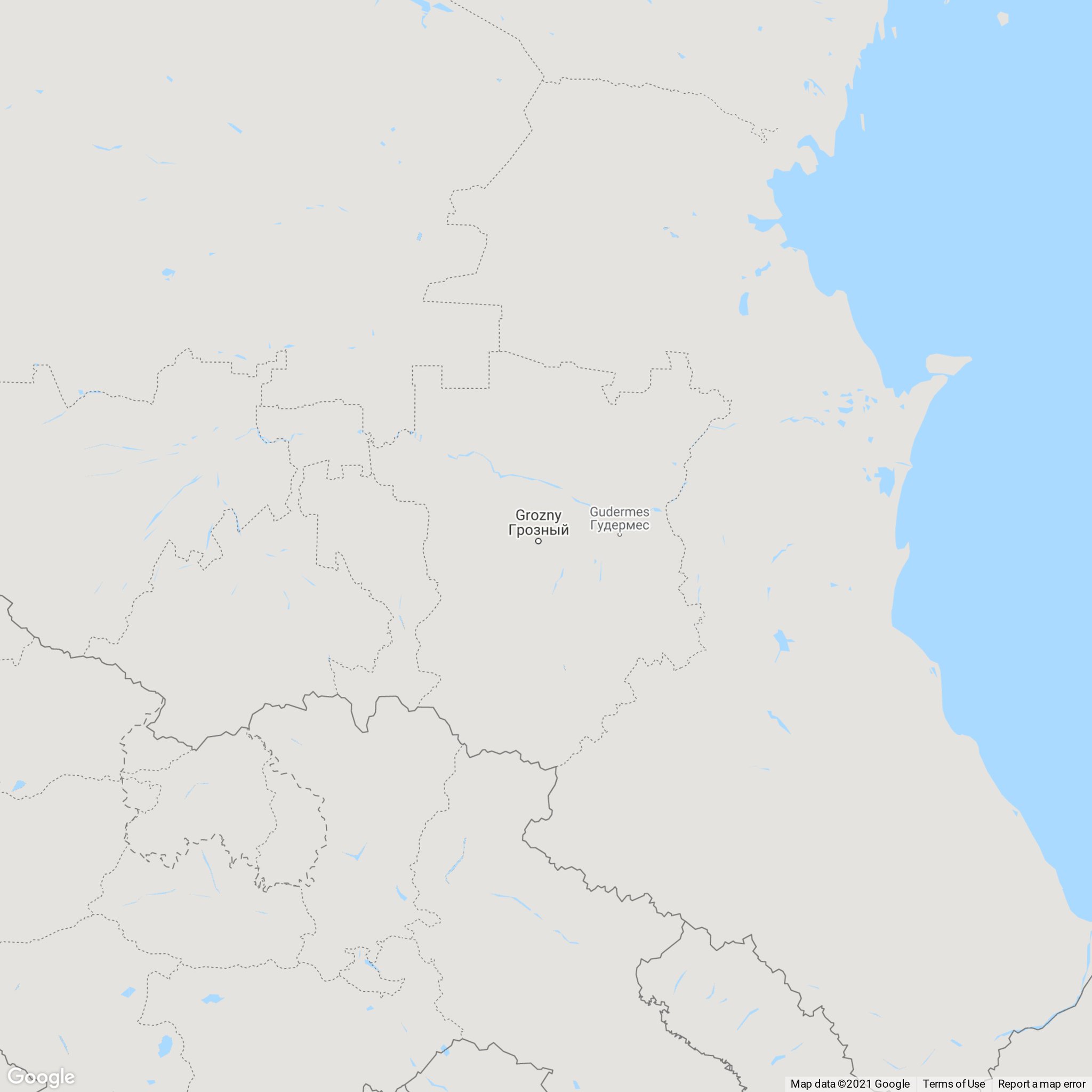

To aid their conquest of the Caucasus, the Russians established Grozny, a frontier fort, in 1818 along with sending a 50 000 strong force. The Chechens and other Muslim peoples united into the Caucasian Imamate to oppose the invaders.

Hit and run guerrilla tactics and a sense of clan honor inspiring the defenders made conquest difficult. The Russians committed more and more resources, quadrupling their initial invasion force by 1857. The conflict ended in 1864 with the annexation of the Northern Caucasus.

But there was peace at least until 1917. The Great October Revolution kicked off the Russian Civil War, a multi-faction mosh pit of the reds, whites, foreign intervention forces, anti-bolshevik left, and nationalist separatists.

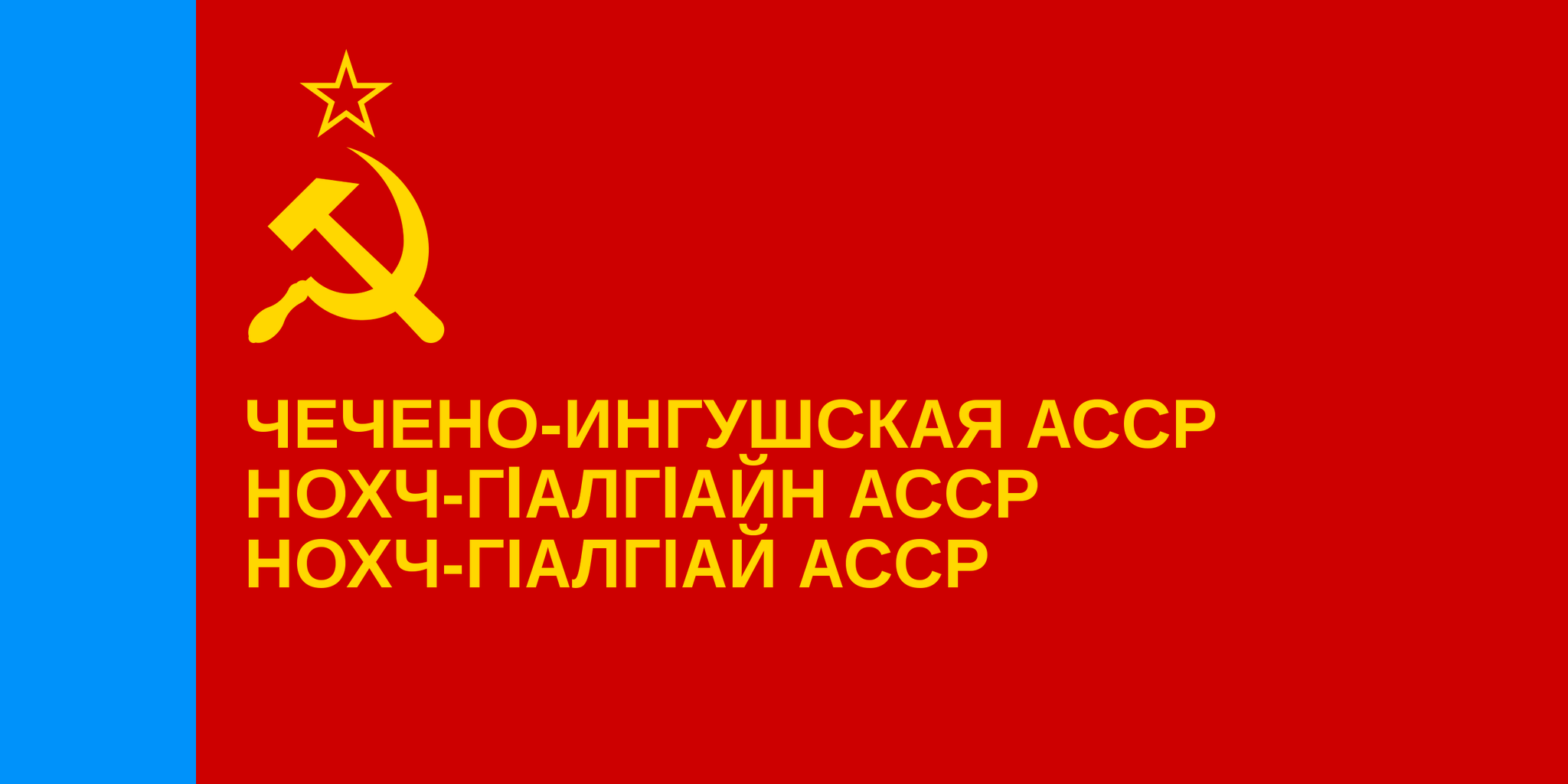

The people of the Northern Caucasus made their bid for independence and formed the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus. The short-lived republic ended in 1921 with a red occupation and incorporated as an autonomy into the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic...

...and not as a constituent republic of the USSR. This is going to be important 70 years later. With Stalin assuming control in 1922 came wholesale oppression. By 1940 a group of Chechen and Ingush intellectuals had enough of Stalin's rule.

Encouraged by the lackluster performance of the Red Army in the Winter War against Finland, they established a guerrilla movement for independence under the leadership of Khasan Israilov, a Chechen journalist and poet.

The Soviets did not respond immediately and in 1941 they were too busy dealing with a non-consensual schnitzel blitz deep into the motherland. The insurrection started small but went into full gear in 1942 with parts of Chechnya seeing an 80% participation rate among males.

The same year the rebel provisional government also received support from the Third Reich. However, the support is somewhat questionable. The Soviets responded with carpet bombings and reprisals against local civilians.

By 1944 the rebellion was quelled and those who survived were deported en masse to Kazakhstan. At least a quarter of the Chechen population perished in these deportations. The autonomous republic for Chechens and Ingushes was stripped of its autonomy.

Khruschev's thaw followed Stalin's oppressive winter and in 1957 the Chechens were officially allowed to return to their homeland. Their autonomy was restored. But as the Soviet Union was still Soviet the policy of Russification was still in place.

Many Chechens only returned in the 1980s after the death of old communist patriarchs. The death of little-known Chernenko in 1985 made way for well-known Gorbachev. The long era of stagnation or zastoy left a mountain of economic and political problems for Gorbachev.

To resolve those he adopted policies of glasnost and perestroika allowing some freedom of speech and decentralizing economic decision making. The policies backfired giving rise to nationalist movements within the USSR.

Gorbachev buckled under pressure and allowed non-communist parties to stand for election in all 15 constituent republics. As a result in 1990, Moscow lost control over six republics.

But most importantly, in what is now the Russian Federation, Boris Yeltsin was elected leader of the largest republic of the Soviet Union. On December 8, 1991, Yeltsin, Kravchuk, and Shushkevich signed the Belavezha Accords, effectively ending the USSR.

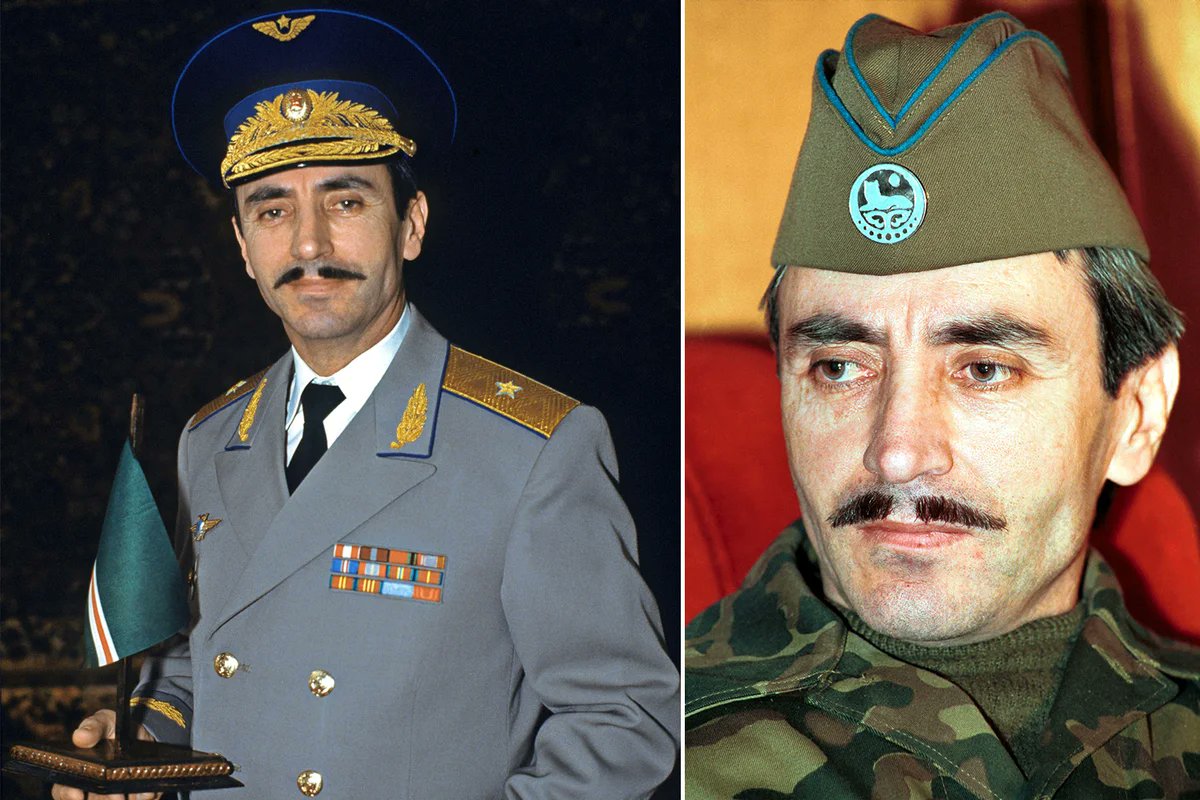

While Moscow was busy putting out fires across the Union in 1990, in Chechnya the local opposition created the All-National Congress of the Chechen People, headed by a former Soviet Air Force general Dzhokhar Dudayev, with the sole aim of creating an independent Chechen state.

On June 8, 1991, the All-National Congress declared the creation of the Chechen Republic. The failed August Coup by communist hardliners in 1991, allowed the Chechen separatists to violently oust the local communist authorities, ending the Soviet rule in Chechnya.

In October of the same year, Dudayev was elected president of Chechnya. The high turnout election was a landslide victory for Dudayev. Those who opposed him in the election shared the desire for Chechen independence with his supporters.

I am not done, to be continued in 2-3 hours

The powers in Moscow called the election and the new authorities and Chechnya illegitimate. After the fall of the USSR in December of 1991, Chechnya declared independence from the Russian Federation. But there was an obstacle to Chechen independence.

While the 15 constituent republics of the Union could declare sovereignty and were internationally recognized, Chechnya was not one of them. Chechnya was part of the Chechen-Ingush autonomy within the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic or the Russian Federation.

So Chechen independence was recognized neither by Russia nor the rest of the world. However, that did not stop Dudayev and his supporters.

With the newly gained de facto independence life in Chechnya for the local ethnic Russian population became less than comfortable resulting in the mass departure of skilled labor. This exacerbated the widespread economic downturn that engulfed all post-Soviet republics after 1991

The dire economic conditions and an inefficient rule of Dudayev's government saw crime rates skyrocket in Chechnya. Kidnappings, murder, robberies, and the production of counterfeit money became common.

This only fueled the discontent with Dudayev's rule and the ranks of his local opposition grew. Dudayev responded by arming his supporters. In March of 1992, Dudayev's opposition attempted an unsuccessful coup later.

They would try again in December of 93, this time with Moscow's financial support. Though they took the Russian money, the opposition had no desire to be part of the Russian Federation, much like Dudayev.

After the latest coup, Dudayev dismissed the Chechen parliament and essentially became an absolute ruler. Yeltsin too had a lot to deal with. He found it hard to fulfill the campaign promises he made for the 1990 election.

The economic downturn in Russia coupled with the teething troubles of the newly free markets made Chechnya a low priority. However, to prevent further disintegration of Russia he first had to ensure that the Federal Constitutional order is recognized by all autonomous republics.

On March 31, 1992 eighteen republics signed the Treaty of Federation with Moscow. Two republics refused to do so on that day: Tatarstan and Chechnya.

On February 15, 94 after a long period of negotiations president of Tatarstan signed the treaty with Yeltsin leaving Chechnya as the only republic not recognizing the authorities in Moscow.

Chechnya was not only a political thorn in the federation side setting a bad precedent for the other autonomies but also an economic one. Russia's economy was and still is heavily reliant on oil and gas exports.

In the early 90s, the only viable way to transport hydrocarbons from the oil-rich Caspian sea was through Chechnya where Grozny is a hub for two major oil pipelines. According to some sources Chechnya never paid for oil deliveries and resold oil transiting through the Grozny hub.

In 1994 Moscow expanded their clandestine support to Dudayev's opposition supplying arms and bankrolling Chechnya's internal conflict. In the summer of 94, a civil war between pro-Dudayev and anti-Dudayev forces broke out. Soon Russian "volunteers" started pouring into the region

The opposition forces attempted and failed to take Grozny in October. They tried and failed again on November 26th but this time at least 70 Russian "volunteers" were captured including operators of the Federal Counterintelligence Service, the forerunner to the FSB.

Three days later Yeltsin issued an ultimatum to all Chechen factions to surrender. When Dudayev's government refused, Yeltsin ordered the federal troops to restore the federal constitutional order. The First Chechen War started.

On 01.12.94 the Russians launched an aerial bombing campaign over Chechnya, while the ground troops were amassed at the border. Ten days later, a three-pronged attack from the West, North, and East commenced with an objective to capture Grozny and oust Dudayev’s government.

Even at its start, the war was unpopular with the Russian public and some high-ranking Russian officers resigned in protest. But there was no stopping now. The leadership in Moscow hoped to achieve a quick victory with overwhelming hardware and troop numbers.

Russian state media called the Chechen rebels "bandits," amounting to nothing more than a few organized crime groups. That kind of thinking would prove to be deadly for the federal forces comprised of mostly conscripts and furnished with outdated maps of Grozny.

As the federal armored columns rolled into Chechnya, they started running into improvised roadblocks and frequent ambushes by Chechen militias. Around that time Chechnya’s chief mufti Akhmad Kadyrov declared jihad, a move that would attract foreign funding and volunteers.

When the underfunded and undertrained Russian Army launched the assault on Grozny on December 31 the city had already been bombed by artillery and the Russian Air Force. What they did not know is that the Chechens did not intend to surrender and had entrenched ambush positions.

Most of the heavy fighting was done within the first few days of the battle with the federal troops sustaining heavy casualties and losing most of the vehicles that had entered the city in the first wave. The Chechen resistance shocked the Russian high command.

General Rokhlin, the commander of the Northern Group, recounted after the war that General Grachev, the Russian Minister of Defense, went on a drinking binge following the events of the New Year’s Eve battle and issued no orders for a few days.

So, the Russians switched their tactics. Indiscriminate artillery bombardment accompanied fierce house-to-house fighting. With the city beaten to a pulp, on February 8, 1995, both sides declared a truce and the Chechen forces started pulling out of the city.

While both military forces sustained heavy casualties, the civilians took the worst of it. In five weeks of fighting more than 17,000 were killed. The federal forces continued to employ the tactics of heavy artillery bombardment and spiced things up with ethnic cleansings.

In the village of Samashki, the Ministry of Internal Affairs troops massacred 100 to 300 civilians. By the summer of 1995, the Russians had control over most of the republic.

Understanding they could not go toe to toe with the Russian federal forces, the Chechens changed their approach to the war. On June 14, 1995, a group of Chechen separatists, led by Shamil Basayev attacked the city of Budyonnovsk in Russia, outside of Chechnya.

They took hostage up to 2000 civilians and issued an ultimatum for a ceasefire and safe passage back to Chechnya. Over the next four days, the Russians made three failed attempts to storm the hospital.

More than 140 civilians were killed, six executed on Basayev’s orders, the rest by crossfire. Basayev got what he wanted. On June 19, 1995, all combat operations in Chechnya were stopped. Whatever was left of the popular support for the war in Russia started to wane.

The ceasefire did not last, but the Russians lost their initiative. On December 23, 1995, the Chechens recaptured Gudermes, a town 36 kilometers east of Grozny.

On January 6, 1996, a group of Chechen separatists this time under the command of Salman Raduev took hostage up to 3000 civilians in Kizlyar and Pervomayskoe in the neighboring republic of Dagestan, autonomy within the Russian Federation.

This time the hostage crisis followed the Chechen separatist attacks on Russian military bases and installations and attempted to use the civilians for safe passage back to Chechnya.

The exact outcome of this attack is sketchy with the Russian authorities claiming a successful hostage rescue operation with only 15 to 41 civilians killed. Most of the attacking Chechens including Raduev managed to return to Chechnya.

A string of federal failures culminated with the Shatoy ambush of a Russian armored column on April 16, 1996. Yeltsin’s public approval ratings were plummeting. With the impending presidential elections in June, he needed a victory and a show of force for the Russian people.

On April 21, 1996, he got exactly that: Dzhokhar Dudayev was killed by two laser-guided missiles fired by the Russian Air Force. On July 3rd Yeltsin secured his second term. Now the war in Chechnya was not a priority for Yeltsin and the Russian people were tired.

Just in time for the third and final battle of Grozny commencing on August 6, 1996. In a fast surprise attack, the Chechens under the command of Aslan Maskhadov and Shamil Basayev isolated the federal forces stationed in the city.

Using captured weapons, the Chechen separatists inflicted heavy casualties on two Russian counterattacks. In the chaos that consumed the city thousands of civilians were killed, thousands more trapped in the bombarded city.

On August 20 General Alexander Lebel ordered a ceasefire and reopened direct talks with the Chechen side. Two days later all federal forces withdrew from the city.

On August 30, 1996, General Lebed, head of the Russian Security Council, signed the Khasav-Yurt Accord with Aslan Maskhadov, the Chechen Prime Minister, ending the First Chechen War. Per the agreement, the federal troops completely withdrew from the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria.

However, Moscow still did not recognize Chechen independence but allowed it to be de facto independent until 2001 when the agreement expired, and the remaining details could be negotiated until then. But we know that turned out.

By various estimates up to 100,000 civilians were killed in the first failed Russian attempt to recolonize Ichkeria.

Mentions

See All

Jason Scott Montoya @JasonSMontoya

·

Dec 12, 2022

- Curated in Chechnya & Russia