Thread

As Financial Twitter is all about hyping the latest news or market move, in macro-land people often tend to miss the forest for the trees.

Let's take a step back and look at the big picture.

Where are we in the long-term macro cycle?

A thread.

1/

Let's take a step back and look at the big picture.

Where are we in the long-term macro cycle?

A thread.

1/

Humanity wants to grow.

Long-term, potential economic growth is mostly driven by demographics and productivity trends.

Cyclical acceleration or slowdown around this trend growth are a function of cyclical fiscal, credit and monetary stances.

Cycles ≠ trends.

2/

Long-term, potential economic growth is mostly driven by demographics and productivity trends.

Cyclical acceleration or slowdown around this trend growth are a function of cyclical fiscal, credit and monetary stances.

Cycles ≠ trends.

2/

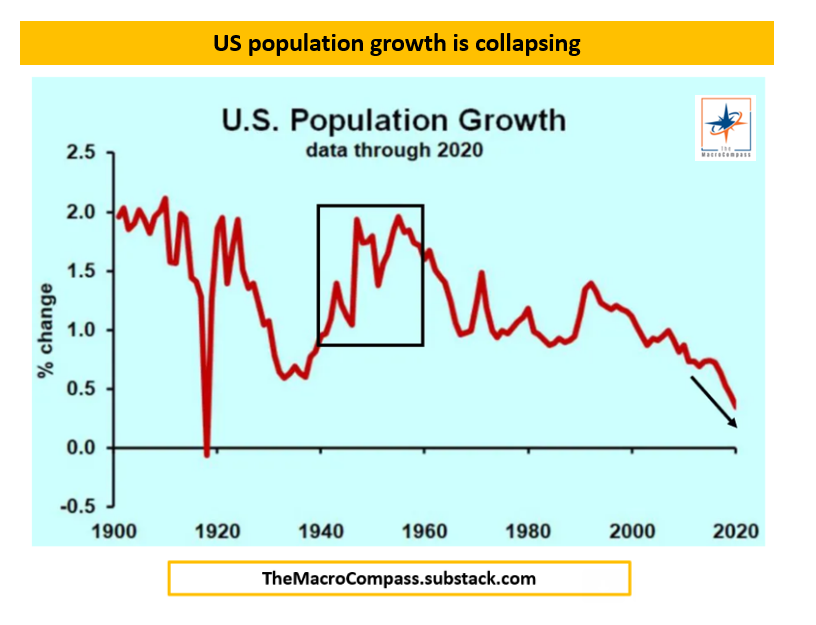

Trend, long-term growth ≈ labor force growth & total factor productivity growth.

The demographics boom broadly peaked in the '60s.

And as it takes 20 years to make a 20-year old, that means that...

3/

The demographics boom broadly peaked in the '60s.

And as it takes 20 years to make a 20-year old, that means that...

3/

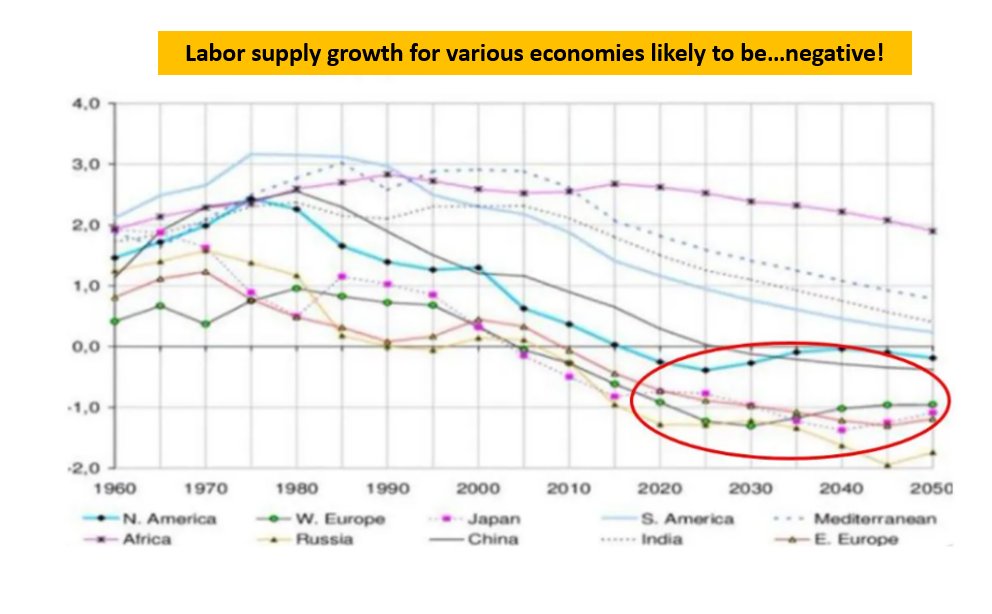

...in most developed economies labor force growth peaked in the '80s.

Right now, the labor force is shrinking (!) every year in the US, Europe, Japan and the situation will only worsen going forward - including a huge drag in China.

Now, picture this.

4/

Right now, the labor force is shrinking (!) every year in the US, Europe, Japan and the situation will only worsen going forward - including a huge drag in China.

Now, picture this.

4/

Inesorably there will be less (!) people actively contributing to economic growth & more retirees: the structural growth pie shrinks

Perhaps productivity comes to the rescue?

Total factor productivity is a function of labor and capital productivity

Where do we stand there?

5/

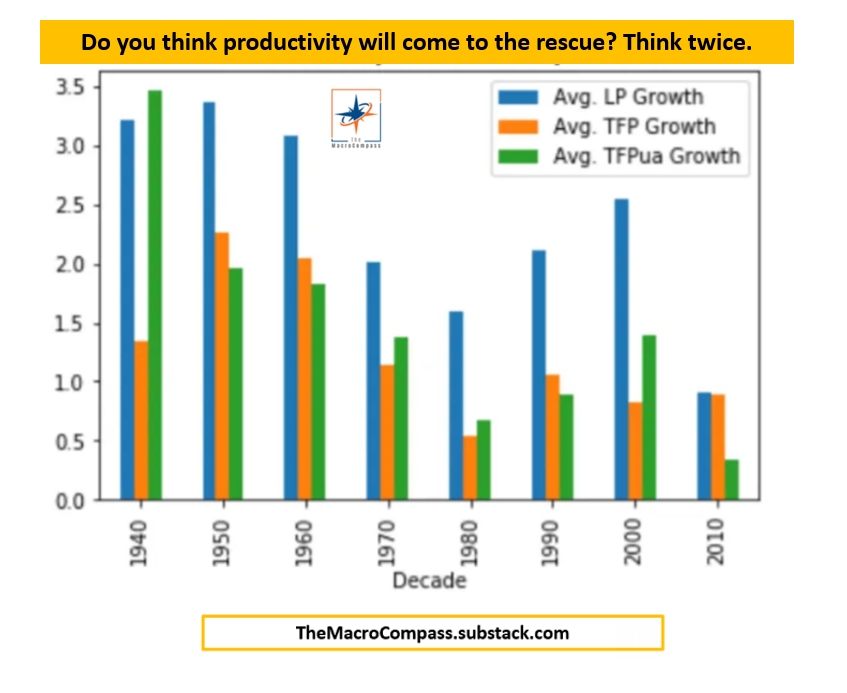

Perhaps productivity comes to the rescue?

Total factor productivity is a function of labor and capital productivity

Where do we stand there?

5/

We become more productive year after year, but the total productivity increments (green bars) become smaller decade after decade.

That's because tech and the move towards a service-based economy have already delivered most of their huge one-off benefits.

As we speak...

6/

That's because tech and the move towards a service-based economy have already delivered most of their huge one-off benefits.

As we speak...

6/

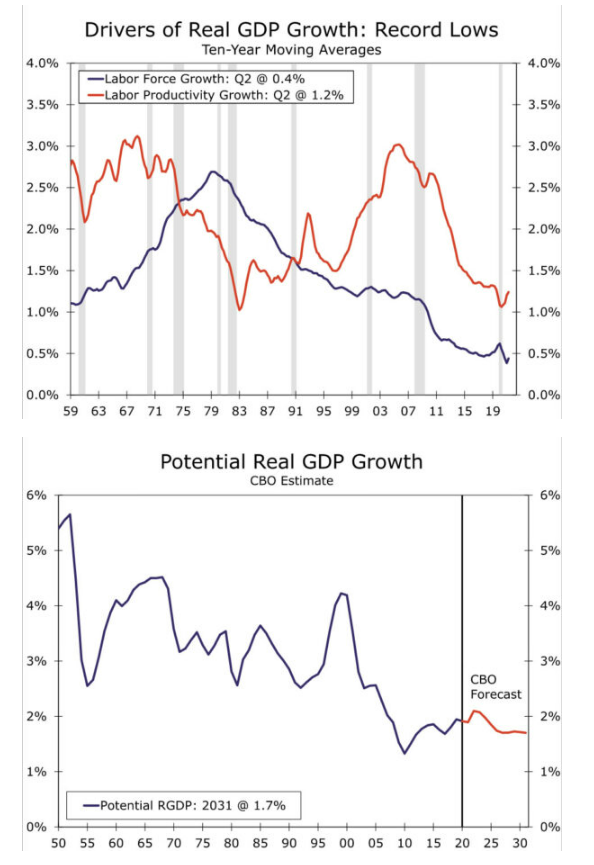

...the marginal increments in productivity are positive but hardly high enough to offset bad demographics unless we have some breakthrough discovery.

Barring that low probability scenario, and given:

Long-term growth ≈ labor force growth & total factor productivity growth

7/

Barring that low probability scenario, and given:

Long-term growth ≈ labor force growth & total factor productivity growth

7/

Potential real GDP growth is now very low across jurisdictions, and estimated to be just about 1.5% in the US (below 1% in Germany).

A 1-1.5% real GDP growth is not a very politically palatable and socially acceptable environment, and so since the '80s we found a fix.

8/

A 1-1.5% real GDP growth is not a very politically palatable and socially acceptable environment, and so since the '80s we found a fix.

8/

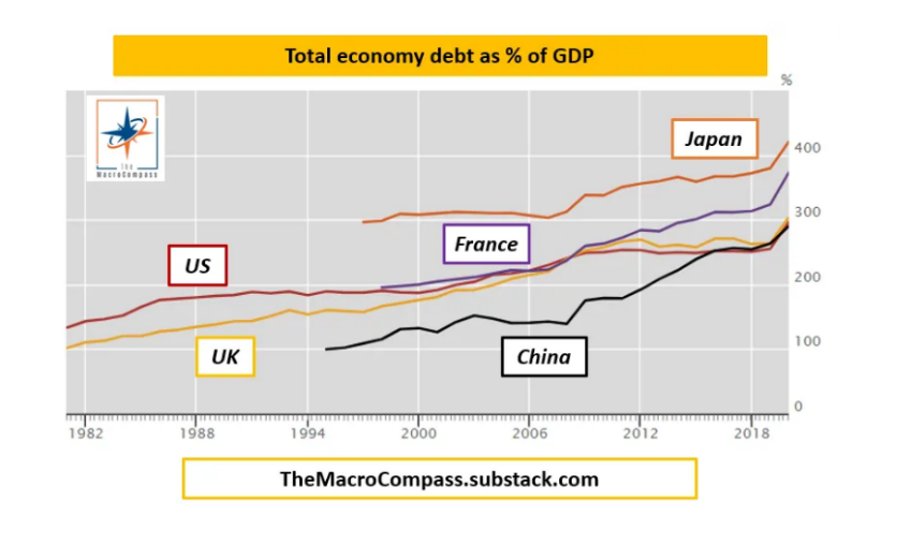

We leveraged up the public and private sector balance sheet to overlay cyclical growth on top of the poor and declining potential GDP trends.

Via inject resources into the private sector (either via unfunded govt deficit or credit creation), we magically engineered...

9/

Via inject resources into the private sector (either via unfunded govt deficit or credit creation), we magically engineered...

9/

...cyclical growth rates that were higher than what we could deliver solely relying on our structural means.

Total debt/GDP is now in the 300-400% area in all major jurisdictions, and counting.

Now, there is a distinction to be made between public and private sector debt.

10/

Total debt/GDP is now in the 300-400% area in all major jurisdictions, and counting.

Now, there is a distinction to be made between public and private sector debt.

10/

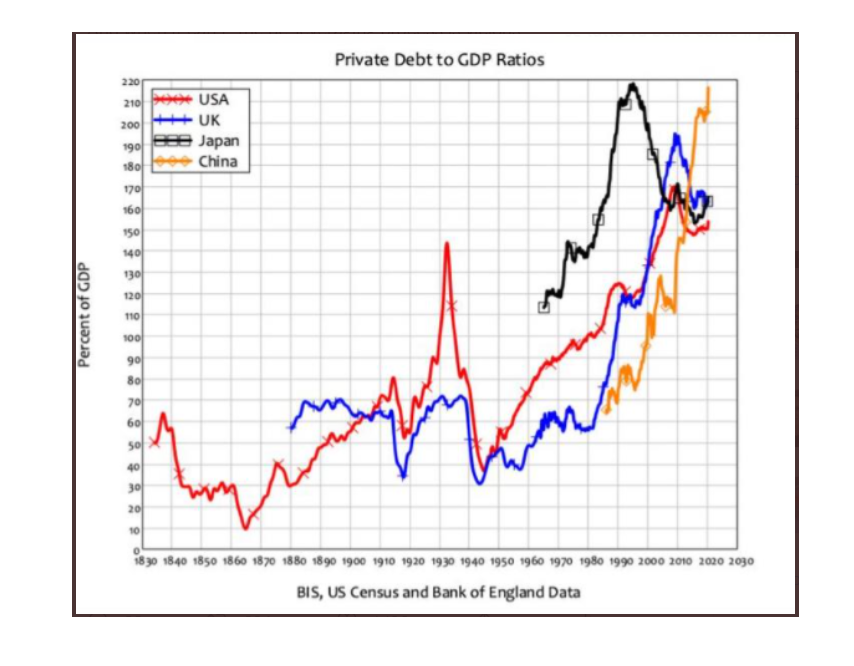

The private sector can't print money to service its increasing amount of debt - it must do so with salaries, earnings, real cash flows.

High levels of private debt massively increase systemic risks: Japan in the '90s, US in the '08 etc etc.

But what if we only use...

11/

High levels of private debt massively increase systemic risks: Japan in the '90s, US in the '08 etc etc.

But what if we only use...

11/

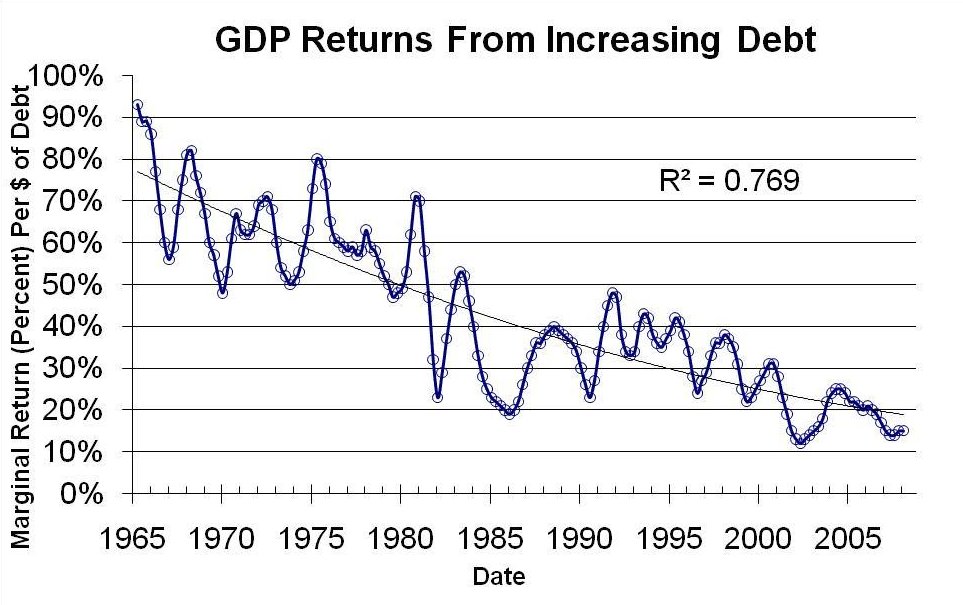

...the government balance sheet and blow a hole in it (permanent deficits) to continuously inject resources into the private sector and help the economy grow?

You can do that, but every $ you spend tends to become marginally less GDP-productive.

And that in turn...

12/

You can do that, but every $ you spend tends to become marginally less GDP-productive.

And that in turn...

12/

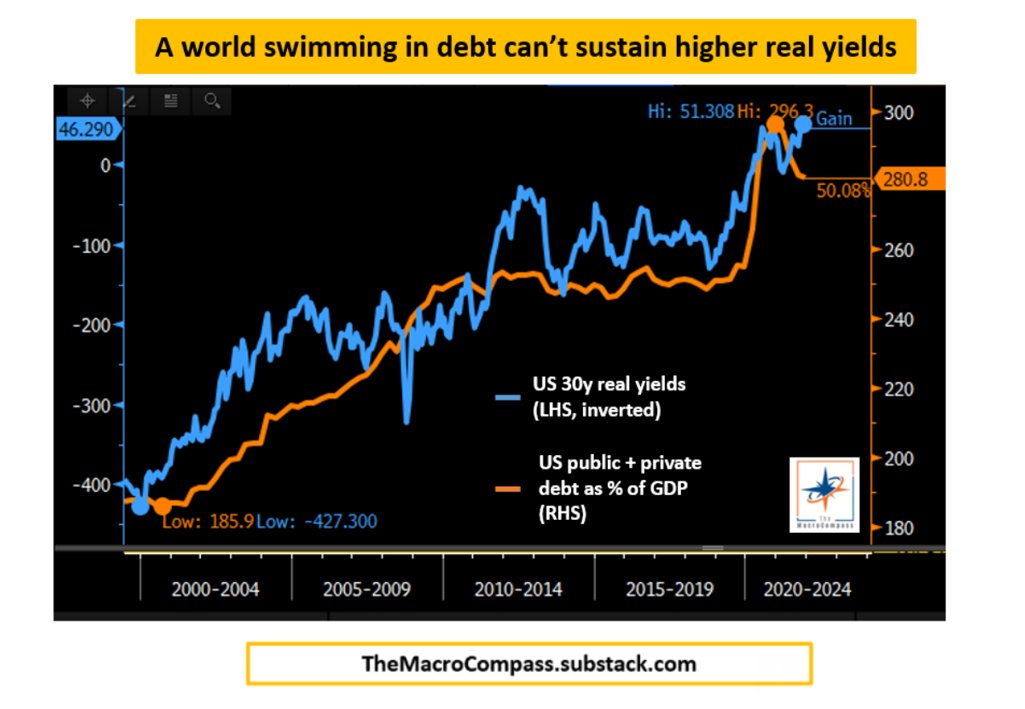

...means that the equilibrium real rates (r*) the whole economy can take to not blow up under this never-ending creation of unproductive debt are..

..lower and lower

Total US debt (orange) charted against inverted 30y real yields (blue): higher debt = lower real rates

13/

..lower and lower

Total US debt (orange) charted against inverted 30y real yields (blue): higher debt = lower real rates

13/

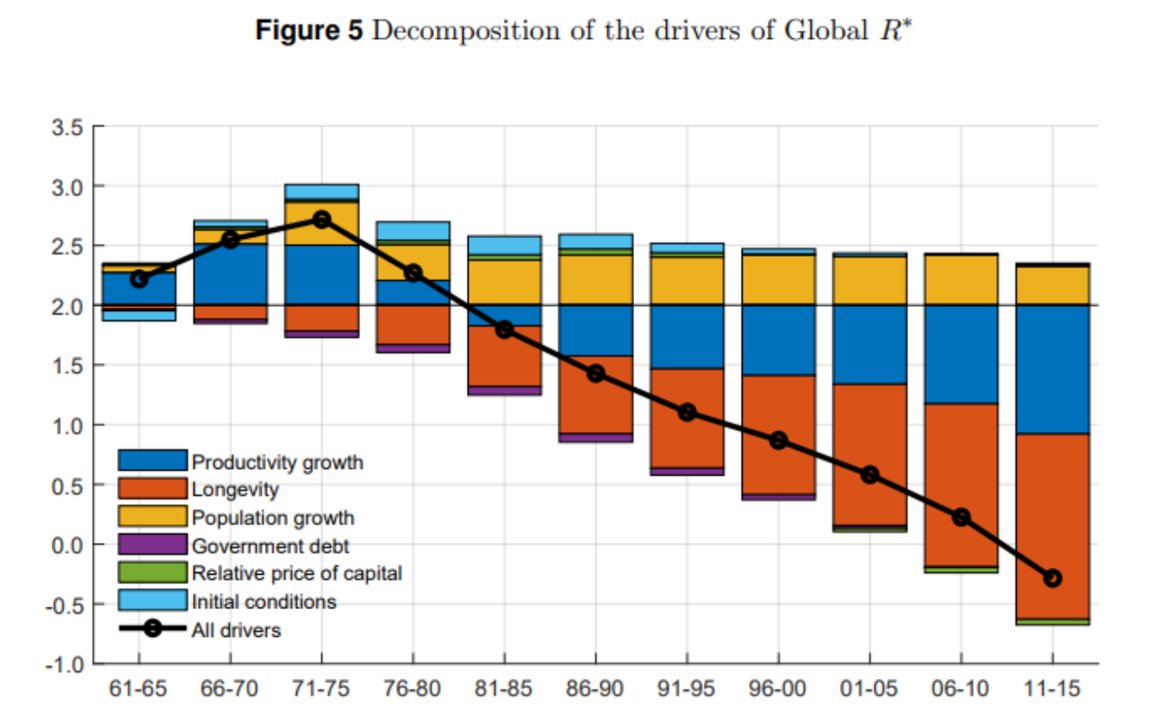

No wonder Central Banks have been forced to relentlessy lower interest rates since the '80s:

- Stagnant or negative labor force growth

- Sluggish productivity growth

- More and more unproductive debt

Here is a decomposition of the drivers behind global r*.

14/

- Stagnant or negative labor force growth

- Sluggish productivity growth

- More and more unproductive debt

Here is a decomposition of the drivers behind global r*.

14/

Importantly, this implies a 4% Fed Funds rate today is much much more restrictive than in the '80s as the economy can withstand less today

The vicinity to the ''effective lower bound'' led Central Banks to accommodate via QE, which floods the financial system with reserves

15/

The vicinity to the ''effective lower bound'' led Central Banks to accommodate via QE, which floods the financial system with reserves

15/

and hence oils the monetary plumbing system and financial markets, leading to sustained periods of low volatility and yield-chasing (see 2017, 2019 etc).

But as Hyman said, stability leads to instability.

Effectively, policymakers decided to apply a quick fix...

16/

But as Hyman said, stability leads to instability.

Effectively, policymakers decided to apply a quick fix...

16/

...which implied the cyclical injection of real-economy money (credit creation and deficits) and the basically permanent injection of financial money (QE).

It all works okay, though sometimes you'll see excessive animal spirits (2021, anyone?) but the real issue...

17/

It all works okay, though sometimes you'll see excessive animal spirits (2021, anyone?) but the real issue...

17/

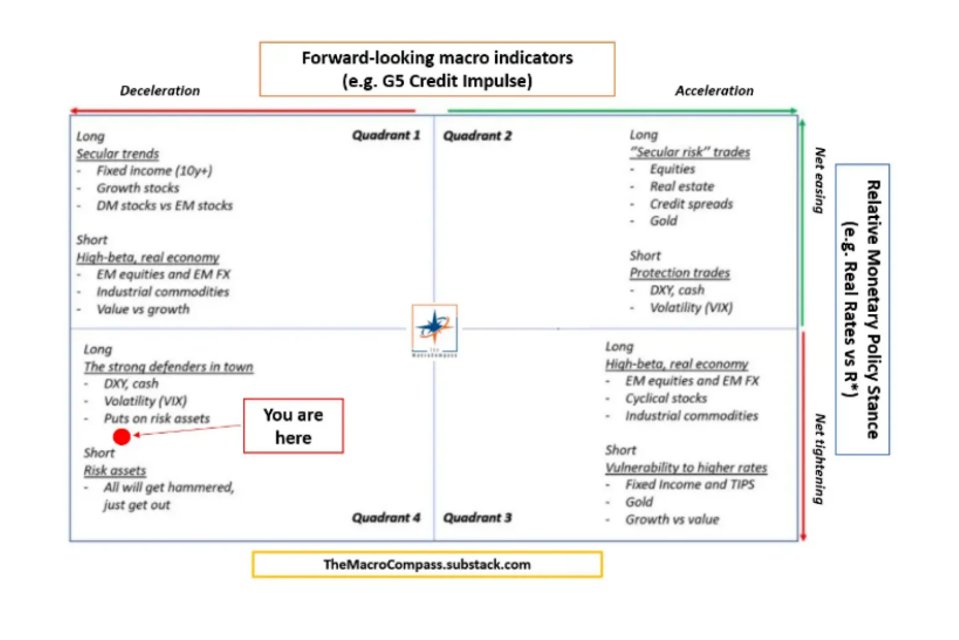

...is what happens when you need to drastically stop BOTH the real-economy and financial money printers at the same time

Like today

You are not only slowing down the flow, but literally halting it or in some cases even reversing it

Can you imagine reverse money printing?

18/

Like today

You are not only slowing down the flow, but literally halting it or in some cases even reversing it

Can you imagine reverse money printing?

18/

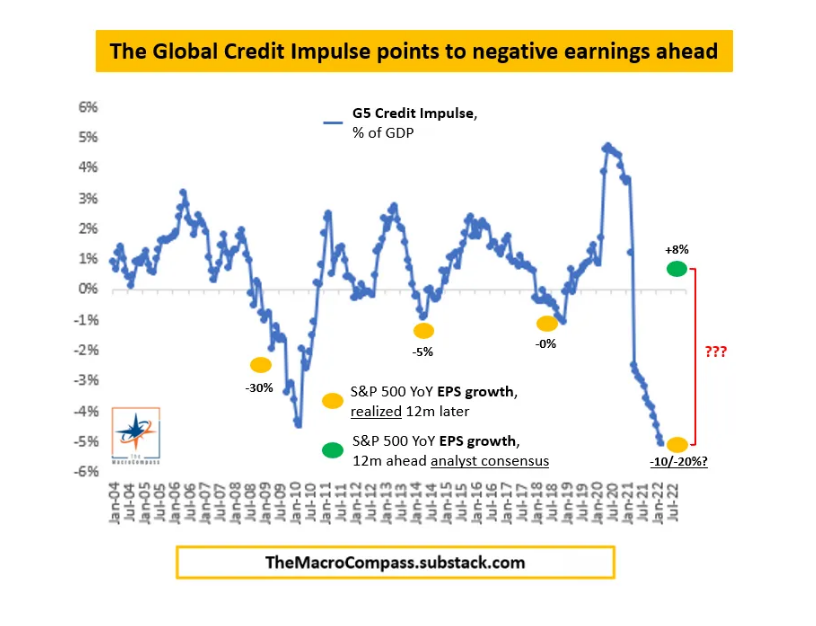

The rate of change of real-economy money creation is now more negative than during the Great Financial Crisis.

Credit creation in real terms has materially slowed down, and in some places outright dropped into negative territory.

Doesn't bode well for cyclical growth.

19/

Credit creation in real terms has materially slowed down, and in some places outright dropped into negative territory.

Doesn't bode well for cyclical growth.

19/

On top of it, the Fed and other major Central Banks are draining reserves (QT) from the financial system.

You should think of it as drying up markets from its lubricant: banks - which are already impaired by regulation - are likely to be more conservatives in taking risks.

20/

You should think of it as drying up markets from its lubricant: banks - which are already impaired by regulation - are likely to be more conservatives in taking risks.

20/

Cyclically, the sharp deceleration in growth coupled with the tight monetary policy stance and draining net reserves from the system leaves long-only asset allocators in a tricky situation - 2022 a major example.

When it comes to long-term macro trends...

21/

When it comes to long-term macro trends...

21/

...we can't fix demographics or productivity easily, but we sure are shaking the foundations of some of the non-inflationary growth pillars of the 2010s:

- Cheap and available commodities

- Outsourced labor + just-in-time supply chains

- Credit expansion + forever low rates

22/

- Cheap and available commodities

- Outsourced labor + just-in-time supply chains

- Credit expansion + forever low rates

22/

BUT.

Don't mix cycles with trends.

If you strongly believe we are at turning points in macro trends, be aware it can take even decades for them to unfold - while macro cycles will inesorably come and go every 12-24 months.

Keep a close eye on both, and don't mix them.

23/

Don't mix cycles with trends.

If you strongly believe we are at turning points in macro trends, be aware it can take even decades for them to unfold - while macro cycles will inesorably come and go every 12-24 months.

Keep a close eye on both, and don't mix them.

23/

I am planning to release a piece on TheMacroCompass.substack.com which goes deep into these long-term macro trends and assess where opportunities might lie given market pricing.

Consider subscribing so you'll receive it directly in your inbox, it's free!

But most importantly...

24/

Consider subscribing so you'll receive it directly in your inbox, it's free!

But most importantly...

24/

...I have major announcements coming up on Thursday for all the subscriber of The Macro Compass.

Mark November 10 on your calendar, you don't want to miss that email :)

Thanks for reading all the way, and enjoy your weekend!

25/25

Mark November 10 on your calendar, you don't want to miss that email :)

Thanks for reading all the way, and enjoy your weekend!

25/25