Thread

Guys, we need to stop this nonsense. Yes, some people go overboard on hype, but the anti-hype backlash is equally as wrong.

A thread born out of frustration on misconceptions about quantum industry👇(1/n)

(it's gotten so bad I've been driven to emojis!)

thenextweb.com/news/oxford-scientist-says-greedy-physicists-overhyped-quantum-computing

A thread born out of frustration on misconceptions about quantum industry👇(1/n)

(it's gotten so bad I've been driven to emojis!)

thenextweb.com/news/oxford-scientist-says-greedy-physicists-overhyped-quantum-computing

Building useful quantum computers is hard, and we're not there yet (despite some hype-y claims). But saying it will never happen, or will take an unimaginably long time, is going against the aggregate view of leading researchers in the field. See: globalriskinstitute.org/publications/2021-quantum-threat-timeline-report/ (2/n)

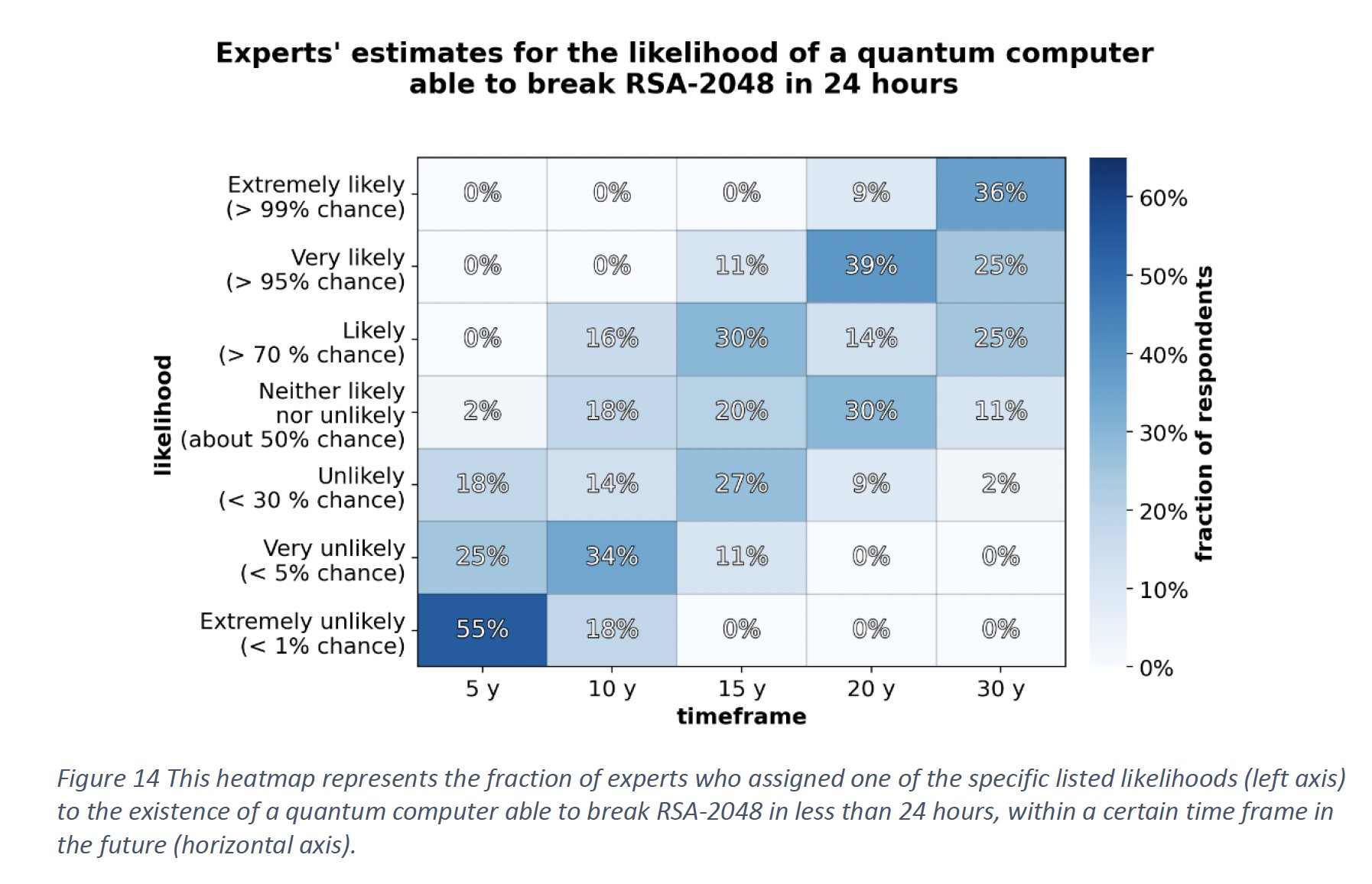

That report encapsulates the distribution of some of the most accomplished research leaders in the space (plus some stragglers like me). By 15 years, the majority give 50% chance or higher of having a QC that can factor RSA 2048. That is a large highly capable QC. (3/n)

The public roadmaps of IBM and Google also project large quantum processors within the 2020s. Noise is still a major issue, but fault-tolerance experiments are picking up pace, and after quantum supremacy, sustained fault-tolerance is one of the next major milestones. (4/n)

Achieving fault-tolerance is definitely hard, but you should be wary of claims that it is incomparably so. These often come from people without direct experience of large scale projects or what can be achieved by a well resourced community working towards a common goal. (5/n)

As a species, we've left Earth, sent probes out of the solar system, mapped our own genome, observed gravitational waves and found the Higgs. Hell, I defy you to watch this SpaceX video and tell me what's too hard. (6/n) youtu.be/bvim4rsNHkQ

Another criticism of commercial quantum computing efforts is an alleged lack of real world applications. However, in my experience this is fundamentally incorrect: I can say with certainty that quantum processing would significantly reduce bottlenecks in our own stack. (7/n)

In some sense, I'm uniquely well placed on this. I have spent a lot of time working on quantum algorithms and complexity theory, but run a company that builds classical software (for programming quantum computers) that has to solve some very hard computational problems. (8/n)

Now, there are certainly charlatans who will claim they can already give you a massive quantum speed-up or that quantum computers can easily solve NP-hard problems, and that is simply not true (barring some breakthrough complexity theory result) ... (9/n)

... however it also leads to people who should know better ridiculing the idea that quantum computers offer an advantage for hard problems (3SAT, travelling salesman etc). And that's factually incorrect. (10/n)

There are actually quantum algorithms for both of these tasks that can be shown to beat the best provable performance of classical solvers. They're just more sophisticated than blackbox annealing or QAOA and still take exponential time, but with a smaller exponent. (11/n)

Another misconception common among physicists is that some knowledge of the physics involved in quantum computing is the only information needed to understand the business case for industrial quantum computing efforts. (12/n)

There is frequently an assumption that effort and resources would only be invested if the investors believed that there was near zero risk, and hence it is often inferred that they are being misled and that any scientists involved have had their morals corrupted by greed...(13/n)

But this fundamentally misunderstands investment in frontier technologies. The best investors in the space, both in terms of those backing startups and tech companies investing in internal efforts, are fully aware of the risk profile of the technology. (14/n)

It also misunderstands the relationship between startup founders and investors. The reality is that, in my experience, the best waybill trust with investors is to make them fully aware of the technology risk and how you approach mitigating that risk for your business. (15/n)

Perhaps the final misconception (well definitely not final, but at least final for me tonight) is that of the motivation of the scientists involved. (16/n)

Speaking for myself, I started @horizon_quantum because I wanted to actually help make quantum computing a real technology that people use and to have the opportunity to actually build something. (17/n)

I've written -lots- of research papers at this point, but as an academic (and as a theorist) the furthest you usually go is as far as a proof of principle experiment at best, and I no longer feel that that is enough to get us to useful quantum computing. (18/n)

I fundamentally believe that large scale quantum computers, and the infrastructure required to take advantage of them, can only really come about as the result of long term focused development in a form that cannot easily be achieved within academia. Why? ... (19/n)

We need to focus on reaching key milestones, rather than on papers and bibliometrics. We need to retain talent within the effort, not kick graduating students and postdocs out the door. And we need to be able to measure and quantify progress towards concrete goals. (20/n)

So, yes, there is hype out there about the promise of quantum computing, and often about very near-term prospects. Some people say and promote factually incorrect things, and we have not yet seen concrete quantum advantage for useful problems... (21/n)

... But the extreme anti-hype reaction we see from some is really not warranted either, and is a different side of the same coin. We really shouldn't lose sight of the fact that quantum computing is our first chance to fundamentally extend computation since the 1940s. (22/n)

So I guess what I am saying is that quantum computing is simultaneously both over-hyped and under-hyped at the same time. Schroedinger's hype, if you will. (23/n)

And I know some out there will read this and ascribe it to a "greedy physicist" trying to cover his tracks. But the reality is that I've been working harder and paid less than I was in academia for the last 3.5 years. And you know what? ... (24/n)

If what if we do succeed in our goals? What if we do help bring an important technology into being and I benefit financially in the process? ... I'm ok with that. I'm not a priest. But it's not what motivates me. (25/25)

Mentions

See All

Michael Nielsen @michael_nielsen

·

Oct 4, 2022

Thoughtful thread: