Thread

The Fed will not pivot

The Fed will hike another 25 basis points this week, and Powell will signal that's likely the last rate hike this year, and the Fed will not cut rates this year. Believe him. 🧵

The Fed will hike another 25 basis points this week, and Powell will signal that's likely the last rate hike this year, and the Fed will not cut rates this year. Believe him. 🧵

Markets and the Fed expect a hike this week and then a pause in June. They disagree on what happens after that. Markets expect the Fed to cut multiple times this year—referred to as a pivot—while the Fed says it will hold rates high and not cut this year. I believe the Fed.

Here are three reasons why:

1) No one wants to be Arthur Burns.

2) Current Fed officials experienced the 1970s and early 1980s firsthand.

3) Inflation is persistent and won’t slow fast enough to declare victory this year.

1) No one wants to be Arthur Burns.

2) Current Fed officials experienced the 1970s and early 1980s firsthand.

3) Inflation is persistent and won’t slow fast enough to declare victory this year.

These reasons may seem simplistic but don’t underestimate the pull of history and psychology at the Fed. Also, these are my views on what the Fed will do, not what it should do ...

1) No one wants to be Arthur Burns.

Know the history. Arthur Burns, Fed Chair from 1970-78, is widely regarded in mainstream circles as the worst Chair in living memory. Powell does not want that same legacy, and the obvious way to avoid it is to avoid Burn’s mistakes.

Know the history. Arthur Burns, Fed Chair from 1970-78, is widely regarded in mainstream circles as the worst Chair in living memory. Powell does not want that same legacy, and the obvious way to avoid it is to avoid Burn’s mistakes.

And what were those mistakes? A pivot!

Ben Bernanke lays out the ‘sins’ of Burns in his book, 21st Century Monetary Policy. Here is a key passage on the disastrous effects of the pivots from Burns:

Ben Bernanke lays out the ‘sins’ of Burns in his book, 21st Century Monetary Policy. Here is a key passage on the disastrous effects of the pivots from Burns:

Anyone, including myself, who 'grew up' as a student of New Keynesian money/macro knows this story. We are taught monetary policy can do good in the world, but not if you do it as Burns did. Again, to avoid Burn's legacy, one must not pivot when unemployment rises.

Rightly or wrongly, Volcker, who was Fed Chair from 1979 to 1987, is put on a pedestal at the Federal Reserve. He is viewed as one who saved us from the high inflation of the 1970s and the mistakes of Burns.

And as Bernanke recounts, here is Volcker on the danger of a pivot:

And as Bernanke recounts, here is Volcker on the danger of a pivot:

At the Fed, Volcker’s words are gospel. That’s the clearest warning against a pivot I could imagine. Volcker intentionally caused a severe recession to break the inflation mentality, and he did not waver until inflation came down. The aversion to a pivot is as strong today.

Furthermore, Volcker apparently had a profound impact on Powell. Powell has spoken highly of Volcker and his approach to monetary policy on several occasions. Here are a few examples from Jeanna Smialek at The New York Times:

Straight out of the playbook. The Fed will not pivot this year, recession or not. History looms large at the Fed and Volcker above all else.

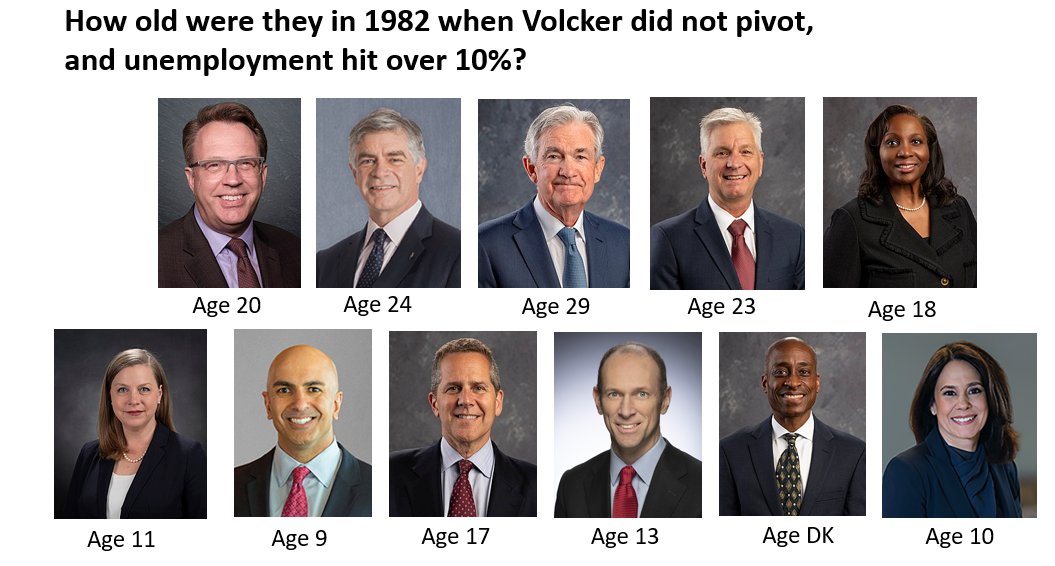

2) Current Fed officials experienced the economic crisis in the 1970s and early 1980s firsthand.

Life experiences matter. True for the decisions we make in our daily lives and true for the policy decisions central bankers make. Malmendier et al www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304393220300490 found:

Life experiences matter. True for the decisions we make in our daily lives and true for the policy decisions central bankers make. Malmendier et al www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304393220300490 found:

How much personal experience has the current FOMC had with high inflation? A considerable amount. Many were young adults during the Great Inflation of the 1970s and its aftermath in the early 1980s. In 1982, Chair Powell was 29 years old, and the others ranged from ages 9 to 24.

According to the research, that experience would increase the emphasis they place on inflation when there appears to be a tradeoff between it and unemployment. The inflation of the late 1970s and the recession of the early 1980s are life, not abstract history, for them.

Regardless of whether they remember it, most Fed officials and the vast majority of New Keynesian macroeconomists (not me) see the inflation in the 1970s as the closest comparison to today. Even if ...

3) Inflation is persistent and won’t slow fast enough to declare victory this year.

In the decade before the pandemic, the Fed faced the opposite problem: inflation that was persistently below target despite low unemployment. That made it difficult to rely on the Phillips Curve.

In the decade before the pandemic, the Fed faced the opposite problem: inflation that was persistently below target despite low unemployment. That made it difficult to rely on the Phillips Curve.

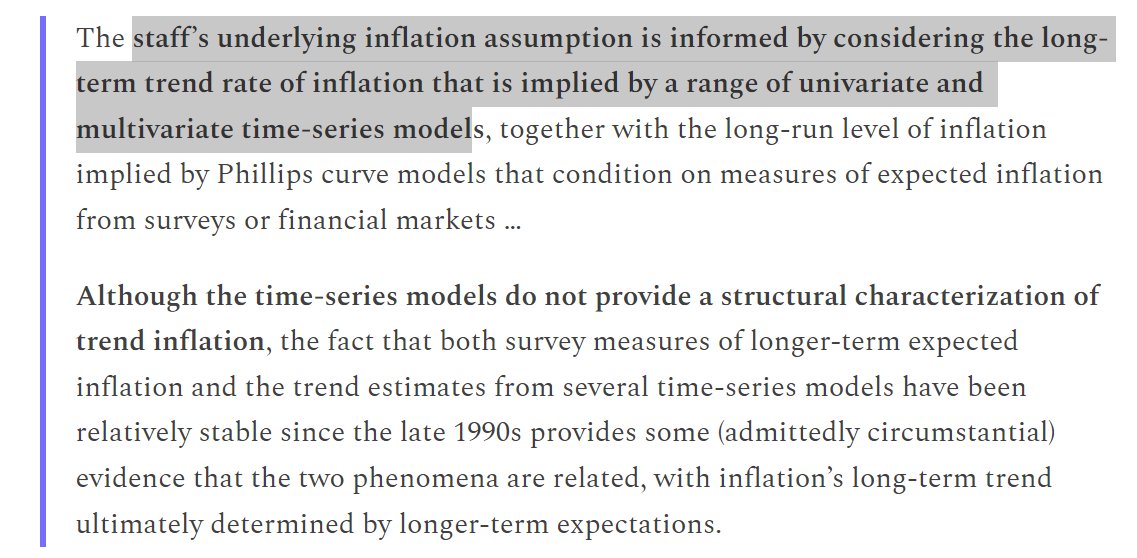

In response, the Board staff turned to a suite of statistical models to explain the lowflation dynamics after the Great Recession. These are more in the spirit of ‘let the data speak,’ as opposed to forcing the data into a structural model. And the trend is slow-moving.

The problem with statistical models is that they project past relationships forward. Numerous historical relationships have broken in this cycle. And in these models, we don’t know why the dynamics are persistent. What’s the story, and to what degree would it apply now? 🤷♀️

Regardless, the Fed’s model will take time to signal ‘all clear.’ Tomorrow's May. There's insufficient time to get a string of PCE core inflation prints sufficiently low this year, even if we go into recession. The Fed won't pivot until it’s clear inflation is beaten. Not 2023.

In closing.

Wednesday, Powell will again tell us the Fed will not cut this year, and again, the markets will ignore him and expect cuts. History and psychology are on the Fed’s side. I don't expect the Fed to blink in a recession or financial market turmoil. And that worries me.

Wednesday, Powell will again tell us the Fed will not cut this year, and again, the markets will ignore him and expect cuts. History and psychology are on the Fed’s side. I don't expect the Fed to blink in a recession or financial market turmoil. And that worries me.

If you would like to read the thread (and more) as a post instead, you can find it on my Subst@ck.

Google: "Stay-At-Home Macro."

(Sorry, I can't put the link in. Twitter doesn't like it.)

Google: "Stay-At-Home Macro."

(Sorry, I can't put the link in. Twitter doesn't like it.)

PS Most frequent comment is pushback on "Powell will signal that's [in May] likely the last rate hike."

My reasons:

- Fed does not like to surprise markets; it must signal June.

- Failure of Silicon Valley and friends is doing some of its work.

- "Likely" only means 50%+ chance.

My reasons:

- Fed does not like to surprise markets; it must signal June.

- Failure of Silicon Valley and friends is doing some of its work.

- "Likely" only means 50%+ chance.

PPS Powell will not be as blunt as me. (Not many people are.) But if you use your Fedspeak decoder ring (I will.) Then you will hear the signal. Yes, Powell will give themselves wiggle room, but no way he leaves the presser without any hints about the next meeting.

Mentions

See All

TXMC @TXMCtrades

·

May 1, 2023

Great thread