Thread

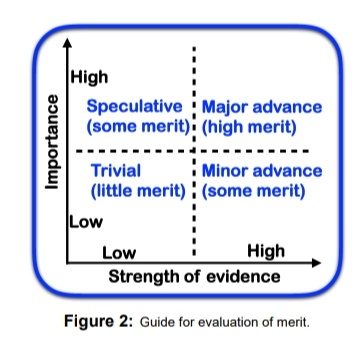

29 scientists write about 'merit' in science and use this figure to 'measure' it. First, I should emphasise we all want great science. Also, merit is not opposed to diversity as the authors suggest - noone wants bad science. The problem is those axes...

journalofcontroversialideas.org/article/3/1/236

journalofcontroversialideas.org/article/3/1/236

Who decides importance?

Is it scientists who go to conferences with buddies and set agendas?

Is it editors based on what gets cited?

Is it rich governments deciding national priorities?

Is it disadvantaged citizens in developing world?

All have different views and priorities.

Is it scientists who go to conferences with buddies and set agendas?

Is it editors based on what gets cited?

Is it rich governments deciding national priorities?

Is it disadvantaged citizens in developing world?

All have different views and priorities.

When we get down to individual levels, and recognising scientists, should we consider resources used? Is it more meritorious to develop a new chemical reaction with a team of 60 and huge national funding, or a team of 2 and a little local support? Simple measures ignore context.

Is a paper in a hot area with 50 citations in the first year more important than a paper in a colder area that only gets 5? And what does that say about how scientists choose problems to work on?

Does work that is more important get featured more in more conference plenary lectures, or does work that is featured in conference plenaries become more important? And what does that say about those who cannot attend conferences?

Even if you do qualitative assessment alongside metrics, who makes that assessment? Did they have a nice meal with you at a meeting? Did their friend train in the same lab as you? Did you invite them to speak at your department? At a bare minimum, we should be aware of biases.

So the idea that 'importance' can be measured on a simple axis is fanciful. It doesn't mean we abandon seeking importance, excellence and merit. It simply means that we understand it has many aspects and cannot always easily be measured.

The other axis, 'strength of evidence', is also subjective, and subject to much gatekeeping. All of us experience times when reviewer 1 says a study is brilliant & well-designed, but reviewer 2 lists a dozen 'missing' experiments.

And as soon as you get into subjective measures of supposedly objective criteria, you have to ask who is doing the judging, who is in the position of power, and what do they stand to lose?

This is broadly the problem with trying to quantify 'merit'. Merit is decided by those who hold the power, who especially in STEM, form 'in-groups'. As such, it is subject to all of the assumptions, little biases, and sometimes outright discrimination, within that group.

Even when machines try and measure merit through simple metrics, we end up with nonsense like this, that has just one woman in the Top 100 chemists, with the Top 100 not even including the female Nobel Prize winners.

research.com/scientists-rankings/chemistry

research.com/scientists-rankings/chemistry

So the thing about merit, is not that those of us who critique it want to sweep it away. We need excellent science. But I want everyone to understand what that merit really is, and to appreciate it is partly a social construct, that is difficult to assess.

So yes, of course we should try and understand 'merit', sometimes we will need to try and assess it - noone wants bad scientists to thrive. We just need to remember it is messy and imperfect, and always question how and why we are doing it.

Most importantly, I want scientists to remember merit can be in unusual places, and understand contributions within a context. Ultimately, I want a scientific enterprise that is open to diverse people to thrive in, is dynamic, innovative, and benefits as many people as possible.

Mentions

See All

Gokce Idiman @gokce

·

May 3, 2023

- Curated in PhD research contents