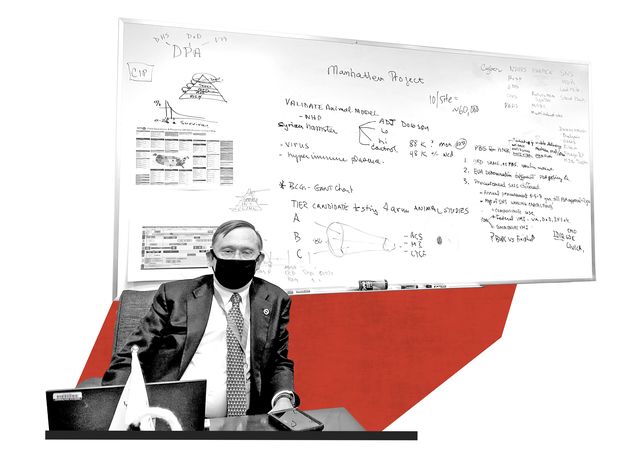

Bob Kadlec was standing in his Washington, D.C., office holding a dry-erase marker, the words Manhattan Project scribbled across the top of a whiteboard. Kadlec, who was known on Capitol Hill as Dr. Bob, was the former Air Force doctor and intelligence officer who ran an obscure division of the nation’s health department called the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response. It was the afternoon of Friday, April 10, 2020, and Kadlec was surrounded by four of his most trusted associates—and a very large stack of pizza boxes. The novel coronavirus had overwhelmed hospitals in New York City to such a degree that the dead were piling up in refrigerated trailers in the parking lots. Recognizing that the country couldn’t shut down forever, Kadlec’s crew had assembled for a brainstorming session here inside the Hubert H. Humphrey Building, a blocky, eight-story structure that houses the Department of Health and Human Services.

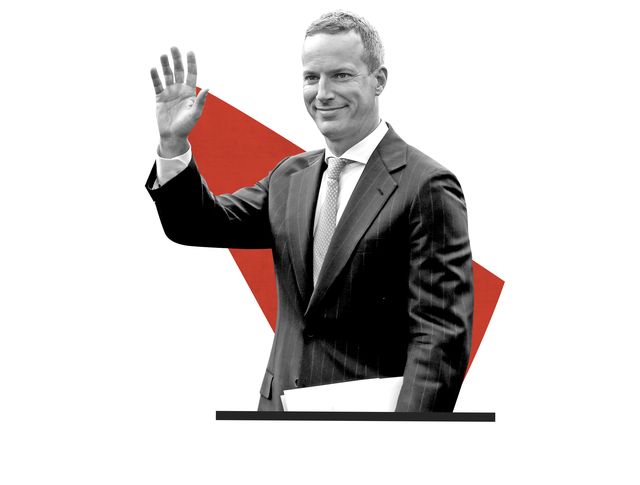

At exactly 5:00 p.m., Peter Marks would be calling. A lanky man with tortoiseshell glasses, Marks was the director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, the referee who would make or break the fortunes of vaccine companies. He was nothing like your stereotypical regulator who said, No, no, no. He was more like, Maybe, huh, yes, eureka! He and Kadlec had a surprising chemistry. And Marks had relayed to Kadlec the conversations he’d been having with drugmakers, including Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson, which to him seemed to have a “defeatist attitude” when it came to the Covid-19 vaccine timeline. Johnson & Johnson was talking about 2022 as a realistic target. Now the two men were setting their sights on a Manhattan Project for vaccines. Their program would be based inside the Humphrey Building, and like the original Manhattan Project, it would bring all the might of American industry and government to the table.

Marks and his team at the FDA were already thinking about how the agency should evaluate an application for an emergency-use authorization for a vaccine. The legal standard was vague. How much evidence were they going to require? Under normal circumstances, when a vaccine candidate entered human clinical trials, regulators in Marks’s office evaluated it every step of the way. But under these extraordinary circumstances, the timeline would have to change. The long-standing problem with running a trial during a viral outbreak is that the surge often wanes before enough cases of disease or death occur in the placebo group. The summer lull that some models were predicting for Covid-19 would be bad news for the large phase 3 clinical trials needed to demonstrate a vaccine’s efficacy. Results might not roll in until late fall 2020, and by then it would be too late to stop the tidal wave of deaths that would come with rising case numbers. What’s more, scaling up the manufacturing process doesn’t ordinarily start until a vaccine is approved, leading to more months of delay. What to do?

Inside Kadlec’s conference room that historic Friday, the phone rang, and Marks’s voice came over the speaker. During their discussions that week, Kadlec had put a challenge to Marks: Sketch out exactly what it would take to issue an emergency-use authorization as quickly as possible using any available regulatory pathway, perhaps even without the benefit of phase 3 data. Now Marks laid out a scenario in which they would run a more intensive set of animal studies than was usual for standard vaccine development, involving mice, hamsters, ferrets, and monkeys.

But in an inspired riff, he took this idea further, to a place not even Kadlec had anticipated. Marks realized that those animal studies could be part of a rigorous competition to evaluate a sea of companies vying to make it big with their coronavirus vaccine. Since the government was funding the whole thing, they wouldn’t just focus on the Mercks and Pfizers of the world; they’d look at underdogs with a promising approach. The government would pay to ramp up manufacturing for those top candidates even while the vaccine was still being tested, so any that were granted the green light could be put into the arms of vulnerable adults immediately. Simultaneously, two or three of the most promising candidates would continue to be evaluated in head-to-head clinical trials. If everything went according to plan, Marks suggested, a vaccine could be rolled out by December 2020.

“How about October 1?” Kadlec asked, polishing off his second or third slice of a pizza. He was famished.

Marks wasn’t going to split hairs. As they spoke, he became amped up, envisioning all the agencies working together “in the truest sense of a team,” as he put it. He felt that there should be close collaboration not only among the U.S. agencies but also with international vaccine efforts. This was a kumbaya moment, “a time,” Marks told Kadlec, “for countries to come together.”

“I don’t know about that, Peter,” Kadlec, ever the military man, chimed in with his realpolitik. Governments were going to look out for their own citizens first. That’s what happened with vaccines during the 2009 swine flu pandemic, and it was bound to happen again.

Chandresh Harjivan, a public-health expert consulting with the government, brought up the cost of a program that would scale up vaccine manufacturing before the final tests had been run. “Money is not a concern here,” Kadlec said, pointing out that more than two thousand people were dying every day from Covid-19 and that the nation was losing tens of billions of dollars each day it was shut down. His boss, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, a business-minded conservative, had told him the country would get a $3 trillion return on a successful vaccine.

Recognizing the national-security importance of the project, Azar and Kadlec wanted to enlist the Department of Defense as a key partner in both the science and the logistics. They suggested calling the effort Manhattan Project 2.0, or MP 2.0, but both Marks and Harjivan scoffed at naming a public-health initiative after a program meant to create destruction. Marks, a Star Trek fan in his youth, said that he was naming his component of the effort, the animal studies, Project Warp Speed, after the technology on the Starship Enterprise that allowed it to exceed the speed of light.

Over that weekend, Kadlec and Marks drafted a memo and a set of slides that Kadlec would share with Azar. Kadlec circulated the materials, including a four-point mission statement, to colleagues at 6:00 p.m. on Sunday, April 12.

Project Warp Speed

Maximally expediting a safe, effective vaccine

A safe, effective, broadly administered vaccine is the single most important solution to the Covid-19 pandemic

MISSION: Maximally expedite the development of a safe and effective vaccine with sufficient scale to inoculate all Americans who need it

DEADLINE: Enable broad access to the public by October 2020

PLAN: Modeled after the Manhattan Project approach, a multi-disciplinary, multi-sector team that brings the numerous in-flight efforts under a single authority to drive relentless coordination, barrier elimination, and accountability for mission success

In the coming week, Azar knew there was only one path he could take to convince the Trump White House to approve MP 2.0, and that particular path went directly to the president’s powerful son-in-law, Jared Kushner, who had been spearheading several coronavirus initiatives. The problem was that Azar, a Yale-trained lawyer, was viewed as an arrogant and ineffective leader and had been ousted as the head of the White House Coronavirus Task Force back in February. His sidekick, Dr. Bob, was even more reviled among some quarters of the administration and had become a scapegoat for shortages of medical face masks, among other crises in the early days of the pandemic. “Kadlec? He’s the one who got us into this mess!” Kushner exclaimed during one White House meeting earlier that spring.

Now Azar was desperate to find some way to regain his standing with the president and some measure of leadership over the pandemic response. To achieve this, Kadlec would have to operate sub rosa, serving as Azar’s inside man at the Humphrey Building, while Paul Mango, HHS’s deputy chief of staff for policy, became the White House intermediary. Mango was a polished McKinsey guy, an operator who could smooth over any turbulence generated by Azar’s jarring presence. Unlike Kadlec and Azar, Mango fit in at the White House in another way: he rarely sported a face mask.

In the early morning of Wednesday, April 15, Azar and Mango headed to the West Wing to talk to Kushner and his onetime college roommate Adam Boehler, who had taken on an advisory role during the pandemic. The meeting was ostensibly about the Strategic National Stockpile, a $7 billion reserve of face masks, life-saving medications, and other supplies, but as it came to a close, Azar presented the concept of MP 2.0. Kushner’s eyes lit up. He opined that Azar’s pharmaceutical-industry experience made him the obvious person to oversee such a program. Kushner would do whatever he could to help him. It was exactly what Azar had been hoping to hear.

Kushner and Boehler went upstairs and caught Donald Trump as he arrived at the Oval Office from his executive quarters, where he typically received his infusion of Fox News each morning. They told the president that Azar had brought them this idea for a Manhattan Project for vaccines. They knew that the speed of the program, light-years ahead of what Trump had been hearing before, would appeal to him. How was that possible? he asked, given everything that Tony Fauci had been saying. They explained that manufacturing the vaccines while they were still being tested would be costly, but it could shave six months or more off the timeline.

“Get it done,” Trump said.

Back at the Humphrey Building that week, Kadlec was coming to a striking realization: MP 2.0 didn’t call for one leader—it called for two. “We need our Robert Oppenheimer and our Leslie Groves,” he told Chandresh Harjivan. Oppenheimer was the physicist who had served as scientific lead of the Manhattan Project; Groves was the lieutenant colonel who took charge of construction efforts and the acquisition of raw materials. They couldn’t win this war without both roles. “Who is going to be acceptable to Trump?” Kadlec mused.

For MP 2.0 to be successful, all of HHS, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the Food and Drug Administration, would have to come together and work as a single operational unit. The leaders of MP 2.0 would best be able to achieve that goal if they came from outside the health agencies and their entrenched cultures.

“You should lead it,” Harjivan said.

“No friggin’ way,” Kadlec replied.

Just as Azar thought his standing at the White House was starting to improve, he learned that The Wall Street Journal was working on a bombshell about how he had tried to cover up the CDC’s testing foibles early in the pandemic. For help, Azar called HHS’s new public-affairs chief, Michael Caputo, into his office. Caputo was a former Republican campaign operative who had been personally installed by Trump to improve the administration’s image. Azar wasn’t happy about the way Caputo was foisted on him without his input, but he was not blind to the benefit of working with a power player. “This is Joe Grogan fucking me!” Azar said. “And I do not want to get fucked.”

Grogan was probably Azar’s biggest detractor in the White House. He was the head of the powerful Domestic Policy Council, on the third floor of the West Wing, and he took on larger-than-life proportions in Azar’s descriptions. Caputo wasn’t sure if Azar was paranoid or onto something, but he knew he couldn’t pick sides in this apparent death match. “If you can’t kill a story, you can hobble a story,” explained Caputo, a disciple of the dirty trickster Roger Stone. He told Azar that they would tape the Wall Street Journal interview. When the story came out, they would take control of the narrative by pointing out everything the reporter failed to quote Azar on. Fake news, they would call it. Trump’s base would eat that stuff up.

That plan fell flat, however. Even after Caputo leaked the recording to a sympathetic news site, The Federalist, the talk around the White House was that Azar was about to lose his job.

Hunkered down in the Humphrey Building, Bob Kadlec and Peter Marks were building the framework for MP 2.0. They now needed to commandeer the nation’s monkey-research capacity as part of Marks’s full-on animal-testing agenda. They had a call with military researchers, including people from the Army’s top biodefense laboratory, in Fort Detrick, Maryland, to discuss their plans. Afterward, Kadlec looked over at Marks and said gravely, “It’s not a good time to be a nonhuman primate in this country.”

An unprecedented scramble for lab animals was also playing out in the private sector. Moving clinical trials from the safety stage to the larger efficacy stages required data from monkeys. China, which supplied more than half of the primates imported to the United States, cut off all exports in April as part of a wildlife trade ban and to preserve its own coronavirus research programs.

Down in Texas, a former Army virologist named Tom Geisbert saw the price of rhesus monkeys double on the open market. “It felt like it was an auction, man,” he said. “You’d be talking to a vendor and he’d be like, ‘Hey, I got twenty rhesus over here, and I’ve got a guy who’ll give me seven thousand; you want to go eight, eight, eight. Going once—ten!’” Novavax, a Gaithersburg, Maryland-based vaccine maker, obtained its baboons from Texas. In Rockville, Maryland, Mark Lewis, president of Bioqual, a pay-for-play lab, turned to cynos—cynomolgus macaques—for his work with Johnson & Johnson and Moderna. He even bought so-called dirty monkeys, which meant they had been born outside a sterile facility. “We were stuck taking whatever we could get.”

Marks was narrowing down the list of ninety-two vaccine candidates the MP 2.0 team was considering. On Friday, April 24, nine days after Trump gave the effort his unofficial approval, Marks emailed Kadlec to see if it was okay for him to start talking directly to companies about the Warp Speed concept. “We need to pressure-test who could be ready for animal studies by June 1 and phase-one studies by early July.”

Kadlec tapped out his response on his iPhone: “Go man go.”

The program had fully captured Marks’s imagination. That Saturday morning at his home, he pieced together a logo for Project Warp Speed, overlaying the image of a syringe atop the arrowhead-shaped shield from the Star Trek franchise. His wife, an artist, suggested he make up buttons, and he spent twenty bucks to order a hundred of them to give out to his future Warp Speed team.

After several days of speculation about Alex Azar’s future, Jared Kushner asked Adam Boehler whether HHS’s head should be fired. Boehler weighed the options. He told Kushner he could go either way, honestly, but Azar wasn’t the root cause of the problem. The real problem was that Azar had been disempowered. “We can’t be in purgatory here,” Boehler said. “Either you fire Azar and you bring somebody else in, or you reconstitute Azar.” Kushner spoke to the president shortly afterward and then told Boehler to go forward with the plan to reinvigorate the secretary.

Boehler asked Azar and Mango to come to his home that Sunday, April 26, with a strategy for the remainder of Trump’s term. He lived on D.C.’s verdant Foxhall Road in a rented $15 million mansion previously occupied by the French ambassador. Another Kushner ally, Brad Smith, was there, and the four men reviewed Azar’s five-point plan. With hurricane season coming up, day-to-day management of the pandemic response would be transferred from FEMA to HHS, but the White House would install a Coast Guard admiral to run the show, limiting Kadlec’s responsibilities and leaving Azar to focus on his top priorities. Azar kept returning to the importance of being protected from his nemesis Joe Grogan, but Boehler kept directing him back to MP 2.0 and his drug-pricing policies. Focus on that and the rest, Boehler said reassuringly, would sort itself out.

Azar wasn’t so sure. Two days later, he read a front-page story in The New York Times about a group at Oxford University whose vaccine, which used a harmless virus as a vector to expose a person’s immune system to the coronavirus spike, was pulling ahead of the competition. He hadn’t heard anything about the Oxford group’s work before, and he felt blindsided. Its leader, Sarah Gilbert, said she was 80 percent confident that its candidate would be proven effective by September.

Azar knew that if he didn’t move fast, he would get an angry call from Trump. He told Kadlec he needed to head that off by figuring out how the vaccine could be manufactured in the U.S. Oxford, he soon learned, was in the middle of signing a $10 million deal with the British drugmaker AstraZeneca.

AstraZeneca wasn’t a major player in the vaccine business, but it was a global company willing to move swiftly, as well aso help supply poorer countries with vaccines. The potential price of the AstraZeneca vaccine at mere dollars per dose (and the fact that it might require just a single dose) gave it a leg up over the mRNA vaccine from Moderna, which could end up costing ten times as much. Azar contacted Matt Hancock, the British health minister, who agreed to connect him to the Oxford effort, but he wasn’t out of the woods yet. Far from it.

Michael Caputo was walking around the Humphrey Building with his cell phone glued to his ear. At 1:45 p.m. that day, Wednesday, April 29, Azar was slated to brief Joe Grogan’s Domestic Policy Council on what exactly HHS had been doing about therapeutics and vaccines. Azar was tense about the meeting, and he and Caputo had been readying a preemptive strike in the form of a positive news story. Caputo had given an exclusive about MP 2.0 to a reporter he trusted at Bloomberg News. A “Joe Friday” type, he called her. As in, “Just the facts, ma’am.”

But that morning, Caputo was also communicating with Maggie Haberman, the New York Times White House reporter. Haberman and Caputo had known each other for many years, and she was a formidable threat. She and two other reporters were working on another big piece about Azar suggesting he was still on thin ice. At best, he was failing to properly manage his people, and at worst, HHS was going to botch vaccine development the way it had diagnostic testing. Haberman wanted a statement. “You know, Maggie, I’d be real careful,” Caputo warned her. He dismissed the gist of the story. It was yesterday’s news. Azar was going to be just fine.

Caputo was now even more eager for Bloomberg to publish its piece before Team Haberman rained on the MP 2.0 announcement parade. In the hallway outside the secretary’s suite, he caught Peter Marks and Bob Kadlec. Caputo told them he had wanted to name MP 2.0 Project Apollo, but that plan had to be nixed after Joe Biden, Trump’s opponent in the upcoming presidential election, spoke about an “Apollo-like moonshot” for vaccines.

“Did you have any other names?” Caputo asked.

“Operation Warp Speed,” Kadlec said, giving a nod to Marks. With the military involved, it could no longer be just a “project.”

“They’re going to think we’re all nerds,” Marks said with a sigh.

Over at the White House, Azar led Marks downstairs to the Situation Room, and Azar took his assigned seat across from Deborah Birx, the Coronavirus Task Force coordinator. Once the meeting was under way, Marks piped up with the run-through of his slides, describing how he and his team had come up with a plan to prioritize fourteen vaccines using a five-point scale under five different criteria, including the status of development and the likelihood of success with a particular manufacturing platform. At the top of the list, with fourteen points, was the vaccine Merck was developing using the same platform as its Ebola vaccine, which had received FDA approval six months earlier. Next up was Sanofi’s protein-subunit vaccine, which earned thirteen points. Tied for third place were the mRNA vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer, with ten points each. Johnson & Johnson and Novavax were in fourth place, while the Oxford vaccine, with just five points, was tied for last place with an obscure company in California.

He then clicked through to a chart showing the parallel development pathways he’d envisioned. According to his calculations, ten million doses could be available under an emergency-use authorization by October 2020, with a goal of three hundred million doses with full approval by January 2021. He was aiming for 80 percent efficacy for the vaccines. The team would select its scientific leader within a week.

At the end of his presentation, Birx scowled at Marks. “These are all unproven platforms,” she said.

Then Mark Meadows, Trump’s new chief of staff, who was sitting directly behind Azar, spoke up: “How much have you made already?”

“We’ve just started the program,” Marks replied. “We’re going to start testing—”

“I can’t believe this,” Meadows said. “Why are we waiting? You need to be manufacturing this at-risk. You should have been doing this months ago.”

Joe Grogan watched this exchange with great interest.

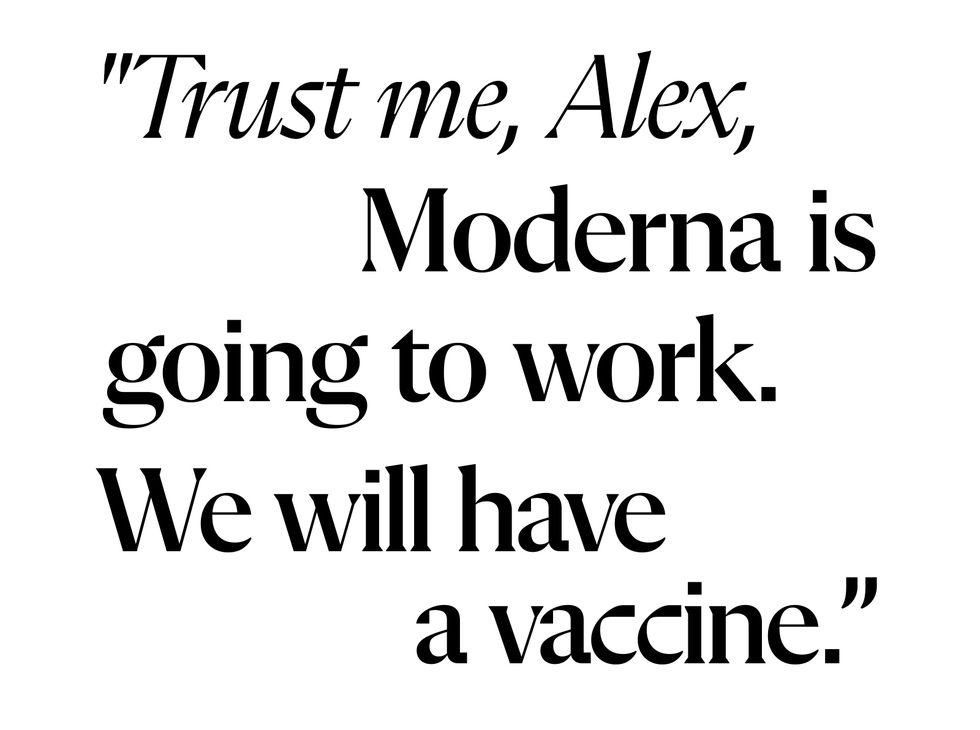

As Azar left the disastrous meeting, Tony Fauci grabbed his arm. “Trust me, Alex, Moderna is going to work,” he said. “We will have a vaccine.”

Marks stormed out, upset that Azar had failed to defend him. Outside, he took one of the bright-red bikes from the Capital Bikeshare racks at Seventeenth and G streets. He pedaled up Pennsylvania Avenue toward his home in Georgetown, blazing through several red lights, as it dawned on him that he had basically been led, unprepared, into a war zone at the White House. He was still panting when Kadlec’s consultant Chandresh Harjivan called to ask how the meeting went.

“I just biked home,” Marks said, “and I didn’t wear a helmet.”

“Why not?” Harjivan asked.

“If I got hit by a car, I’d probably be better off.”

When Marks stepped inside his home, he opened up a link to the Bloomberg News story, which had gone live at 2:08 p.m. “Trump’s ‘Operation Warp Speed’ Aims to Rush Coronavirus Vaccine,” read the headline. It was really happening. Maybe the day wasn’t so bad after all.

After the meeting, Alex Azar left the Situation Room and learned that Maggie Haberman’s negative story about him had come out in The New York Times. Azar thought it had Joe Grogan’s fingerprints all over it. He found Adam Boehler in the lower lobby of the West Wing and told him that he would resign as secretary if he had to keep enduring Grogan’s attacks. Hours later, Grogan announced that he was resigning from his position as head of the Domestic Policy Council—a plan, he told reporters, that had long been in the works.

With one less adversary to worry about, Azar was riding high on his way to the Pentagon two days later, on Friday, May 1, for a 7:30 a.m. meeting.

Once he was inside, a military aide and several assistants guided him through the outermost ring of the Pentagon, the E Ring. They came to the large, nondescript Nunn-Lugar Conference Room, across the hall from the secretary’s suite. Adam Boehler was already there on one side. On the other side sat David Norquist, the deputy secretary of defense, and Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Azar sat along the third side with his chief of staff. After a few minutes, the defense secretary, Mark Esper, came in. Jared Kushner was the last to arrive.

During their first in-person meeting, the assembled power brokers laid out how the DoD would give Operation Warp Speed the logistical support it needed to move supplies and distribute vaccines. They discussed the organizational structure, and everyone agreed that it was critical that the Warp Speed team be self-contained, a single unit placed inside a protective cocoon to minimize the involvement of the feuding factions at the White House.

“We want to keep it clean,” Azar said. “We want to keep it out of the grips of the task force.”

But because Operation Warp Speed was engaging multiple branches of the government, the White House would require some nominal form of representation, and the men decided that Kushner and Boehler would serve on a board of directors with Azar and Esper. Later, they would add Deborah Birx, Francis Collins, Tony Fauci, and Robert Redfield as nonvoting advisers.

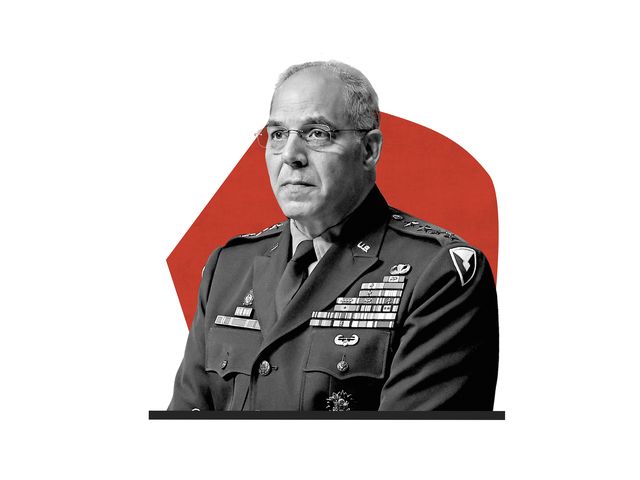

So who was going to lead this thing? The men sketched out a picture of the person on top, the Leslie Groves character who would need to manage both the daunting number of supplies required for the vaccines and, ultimately, the distribution of doses. Esper told Milley, “This sounds like a Gus Perna job.”

Gustave Perna was a four-star Army general, one of only forty-five in the nation holding the military’s highest rank. Perna led the U.S. Army Materiel Command, headquartered at Redstone Arsenal outside Huntsville, Alabama, and he was on the verge of retiring. An imposing man with a superhero-size torso that seemed like it was about to burst out of his camouflage fatigues, he had deployed to Iraq three times in his career, commanding resupply operations. What Perna lacked in scientific knowledge he made up for in instincts and in his ability to distill a complex problem into exactly what he needed to know to make a life-and-death decision.

Over the next week, Operation Warp Speed settled on its Oppenheimer, the technical lead who could work with the companies and oversee the experts at the various health agencies. Moncef Slaoui, a Moroccan-born scientist, had been head of vaccines at GlaxoSmithKline and had shepherded fourteen of the company’s vaccines through approval, a record that no one else could compete with. So revered was Slaoui at his former company that it named its Maryland vaccine center after him. Since his retirement, he’d been serving on the board of Moderna, where he had gained a deep knowledge of its mRNA technology.

Slaoui planned to throw out much of Peter Marks’s work. For his version of Warp Speed, he would handpick the companies himself and give them more freedom in developing their products. His confidence made him everyone’s first choice, but his biggest problem was that he was a walking financial conflict of interest. He got paid for being on the boards of companies that Warp Speed was going to give hundreds of millions of dollars to.

Kushner argued that this wasn’t enough of a reason to go with one of the timid bureaucrats further down the list. It was decided that Slaoui would have to be brought on not as a government employee but as a consultant, a title that would trigger fewer ethics requirements. Slaoui would also have to agree to donate any gains in his stock portfolio to the NIH over the course of his term.

The scientist’s black Ferrari soon roared into the parking lot of the Humphrey Building for his first day of work. When Michael Caputo went to greet him in a conference room on the sixth floor, Slaoui had the look of a man at ease in his position, sporting designer jeans and a black leather jacket.

Caputo told Slaoui that if any reporters called about his role, he was to say nothing. Slaoui was going to give an exclusive interview the next day to Maggie Haberman. Once that was done, he would be sequestered to focus on his work. “You’re going to get kicked in the balls once, maybe twice,” Caputo said matter-of-factly.

“Kicked in the balls?” Slaoui asked with a look of puzzlement.

“Yeah, kicked in the balls. About your stock portfolio,” Caputo said.

“Why? I’m going to lose millions over this,” Slaoui responded.

Around 11:00 a.m., Alex Azar took Slaoui over to the White House to meet the president. Mark Esper had come with Gustave Perna. Jared Kushner brought them all into the Oval Office together. Trump looked admiringly at Perna in his brown four-star-general dress uniform. Esper briefed the president on Perna’s military career and made a point of noting that he was from New Jersey, which he knew Trump would appreciate, as so much of his real estate empire had been built there. Trump was awed by the initiative and excited by the idea of the military carrying out the distribution.

“These are the best people on earth,” Kushner told his father-in-law. “We are going to get the vaccines we need.”

“Can we really get a vaccine in a year?” Trump asked Slaoui.

Slaoui told him it was doable, but there were no guarantees in the vaccine business. They were going to give it their best effort. Trump said that was fantastic, just fantastic.

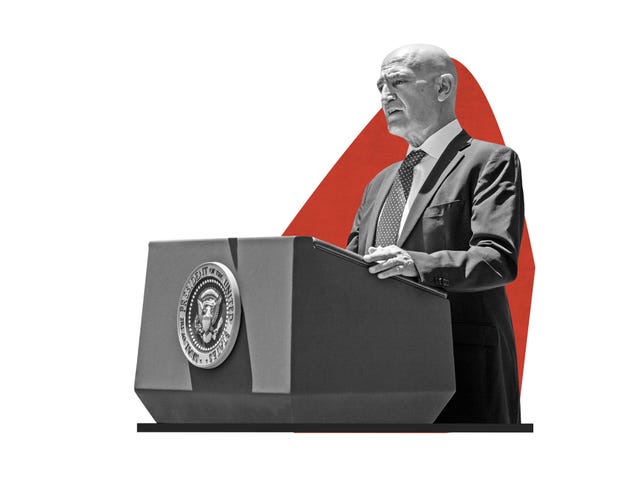

The following afternoon, Alex Azar was in his motorcade heading out to an event in Allentown, Pennsylvania, with a supplier for the Strategic National Stockpile. He had almost reached Baltimore when he got a call. Change of plans: Trump wanted him back immediately. The president was fuming about that day’s media coverage of Rick Bright, a government-vaccine-expert-turned-whistleblower who had just testified in Congress about the administration’s botched Covid response. Trump wanted to drown it out with news of his own making. Azar would join him at the White House; they would announce Operation Warp Speed, then head to the stockpile together to show how committed the president was to fighting the pandemic.

Azar’s vehicle boomeranged back to the capital. When he arrived at the White House… another change of plans. The press team decided the announcement should wait until the next day. Trump, however, would still head out with his health secretary. They crossed the White House lawn to board Marine One, and as they passed the gaggle of reporters, Trump told Azar to “hit back hard” on Bright.

Azar didn’t hold back. His face was flaming red as he blasted the whistleblower over the roar of the helicopter engines. “Everything he is complaining about was achieved,” he said, delivering one of his trademark tirades. “He said we needed a Manhattan Project for vaccines. This president initiates a vaccine Manhattan Project, diagnostic Manhattan Project, therapeutic Manhattan Project.”

While the secretary caught his breath, Trump sputtered a few remarks about Bright being “an angry, disgruntled employee” who “didn’t do a very good job.” Then they boarded Marine One and the president sank into his plush gray seat. A grin hung on his doughy face. Azar felt a sense of relief. The center of power had been restored to the Hubert H. Humphrey Building.

Adapted from THE FIRST SHOTS by Brendan Borrell Copyright © 2021 by Brendan Borrell. Reprinted by permission of Mariner Books/HarperCollins Publishers.