Digital Theme Park Platforms: The Most Important Media Businesses of the Future

Chapter One: The Past

Disney is the envy of every media company, regardless of whether it focuses on film, TV, gaming, music or publishing. In plain terms, there has never been a more dominant entertainment company, globally or in the US. It has a brand that actually matters to consumers, owns franchises that consumers essentially treat like subscription content services, and operates the biggest star-making platforms in the world. And as strong as this platform was at the start of 2019, it exited the year even stronger. In a matter of weeks, Disney’s brand new direct-to-consumer platform acquired 30MM subscribers.

The deeper we get into the digital era, the more dominant Disney seems to become. After all, it was long expected that the Internet would disrupt dominant media companies and IP via rights infringement and the emergence of myriad user-generated “franchises”. However, one of the biggest storytelling “lessons” in the 20th and early 21th century was that audiences have an unending desire for “more” of the stories they already love. And the Internet has enabled this to an unprecedented degree. You can constantly track production (cast Instagrams, behind-the-scenes featurettes, and leaks on social media), engage in fan communities (message boards and YouTube theory/Easter egg videos), consume endless amounts of fan content (e.g. fanfic and watch-along podcasts), play this content back on demand (e.g. Netflix), and engage in never-ending and constantly updated online multiplayer games (e.g. Star Wars: Battlefront 2). This is a powerful, self-sustaining financial and cultural flywheel. And Disney has many of the franchises that best lend themselves to this model. Many of those they don’t own, such as Harry Potter, have their rights fragmented.

But what is the strongest, most profitable, most defensible part of Disney’s business in the digital era? Its capex-heavy, physical theme parks.

There is no simple way to quantify how important this business unit is to Disney. The financial role is obvious. Disney’s Parks & Attractions segment generates nearly 100% more revenue and 60% more profit than Disney’s studio division (which already generates nearly three times the revenue AND three times the gross margins as its primary competitors). By turning hit films into theme park attractions, not only does Disney generate more “upside” from a hit than its competitors do, Disney’s breakeven point for these films is also much lower. But the parks are much more than this direct financial benefit. There is nothing that can compare to the impact of a child being hugged by her heroes. The ability to enjoy your favorite IP as “you” is unique and lasts a lifetime. Consider, for example, how many families have Disneyland photos of their kids with Mickey or Woody on the fridge. Or how many of these kids have kept those photos decades later (and compared them to their eventual spouse’s version of that same photo).

And because of real estate scarcity, lengthy build times, enormous capital requirements (exacerbated by Baumol’s Cost Disease), Disney’s theme parks, resorts, and cruises are incredibly difficult to replicate by another Western media company. It would take twenty years and tens of billions of dollars for AT&T/WarnerMedia to receive permits, design attractions, and build a fully operational theme park, for example (and it’d probably be in the middle of nowhere). It’s especially hard to imagine all of this occurring while the company is investing tens of billions per year into HBO Max, new 5G network infrastructure, and maintenance capex (while also sustaining tens of billions in dividends and debt service, and fending off agitated investors). Comcast/Universal has an ambitious plan to grow its parks footprint, including new resorts in Russia, South Korea, and Singapore. However, these will take years and tens of billions of dollars. Purely comping the number of parks also overlooks the scale differential. Disney’s Orlando resort, for example, is over 25,000 acres (half used). Universal Studios Orlando is barely 500. In addition, Disney operates four cruise ships (another three are due by 2023), while no competitor does. Overall, Disney’s theme parks business generates more than $26B per year with 175MM+ visitors, compared to 6B for Universal Studios, with 50MM.

However, the defensibility and value of these businesses goes beyond physical and financial barriers to entry; running a successful theme park means far more than designing a fun ride. Giving real hugs to kids is incredibly dangerous — doing this reliably, safely, and positively millions of times per year requires enormous training (the parks also operate hospitals, pet day care and police services, too!). In addition, these parks must cater to a wide variety of different customers with different needs, physical capabilities, and developmental maturity. In contrast, a film or TV show has only one version that lasts forever and is infinitely repeatable with 100% consistency. There is no other “medium” in the entertainment industry that requires melding more art forms (e.g. live performance, set design, music, engineering) with a smaller margin for error, and at such a great scale. The benefit, though, is a rich, hard to replicate and intimate understanding of the consumer.

The competitive consequences are profound and only growing. Fans simply cannot enjoy DC or Lord of the Rings or Dragon Ball the way they do Disney’s Princesses, Pixar, most recently, Star Wars, and soon, the Avengers franchises. This fundamentally limits a franchise’s ability to grow love — the lifeblood (and profit driver) of all IP-based companies.

Related Essay: Disney, IP, and “Returns to Marginal Affinity”

This is why brands like 20th Century Fox and WarnerMedia license their theme park IP from super-popular brands like Avatar, The Simpsons, and Harry Potter to their competitors, Disney and Universal. Nintendo also partnered with Universal for its theme park rights. This extension is strategically important and financially valuable, but it’s also quite costly. The rights owner, for example, neither owns the customer relationship nor do they deliver the end-customer experience (in a weird way, Universal has a closer relationship with Harry Potter fans than WarnerMedia does). In addition, the majority of associated profits go to the park operator — who also gets to intermingle their IP and draft off the popularity of their competitors’ franchises, too. That’s risky in an age where franchises and clarity of franchise ownership is key.

So, as we embrace the digital era, it’s funny to consider the enduring and durable significance of the analogue theme parks business. It is incredibly profitable and will continue to grow as new mobile technology/personalization enhance the park-going experience. The barriers to replication are incredibly high and span both fixed investment (land and infrastructure) and skillset (e.g. design and boots-on-the-ground operations). It also offers an intimate understanding of the consumer, is particularly potent when connected to an IP flywheel, and is able to constantly renew its appeal through new attractions and updates.

Chapter Two: The (Start of the) New Theme Parks

These parks exist and thrive because of our desire to be “inside a living story”. This was Walt’s primary goal with Disneyland: to go beyond passive consumption and into active immersion. Consider the following quote from one of Disney’s chief Imagineers:

“Disneyland is an experience involving many moving parts in harmony, like an orchestra. Everything has to be tuned, what you hear, what you smell, what you see, how you see it, the speed at which you assimilate all of that, just like a film, is choreographed. But how do you choreograph that if you don't control the camera, because the camera is you — it's you when you come to Disneyland".

This idea of agency is key. There’s only so much time one can spend in a physical or virtual world as a pre-defined character. That doesn’t mean we want to remain an exact replica of our “IRL” selves — we might want to be taller, or blue, or metal, and so on. But when you’re specifically Iron Man, there are limits to what you can look like, how you can behave, what you can do or be, where you can go, and how long it makes sense to be there. After all, you can’t actually be Iron Man, just pretend to be. And certainly, it doesn’t make sense if all of your friends are all Iron Man, too.

For decades, the only real way to experience a digital world with agency and an individual sense of self was to go to the theme park. Games have been on the cusp of these experiences for years, but in 2020, they’re well under way. These are “games” like Minecraft, Fortnite, Roblox, to a lesser extent GTA Online, and Pokémon Go.

These titles offer many unique advantages compared to their analogue analogues. For example, they are always “open”, “everywhere”, “full of your friends”, and impervious to COVID-19. These games also boast an even larger (i.e. infinite) number of attractions and rides, none of which need be bound by the laws of physics or the need for physical safety, and all of which can be rapidly updated and personalized. These digital parks also allow for much greater self-expression (e.g. avatars, skins).

These attributes help explain the enormous and unprecedented popularity of the titles. Each month, each of these four titles delivers 1.2–1.5B hours of playtime across their 75-120MM individual MAUs. And this is before adding in hundreds of additional hours of YouTube and Twitch viewing. No other content/media experience has ever come close to this popularity. For comparison, Lego is only 400MM monthly hours of play globally and has no comparable technological hurdles. According to some reports, more than 50% of kids 9–12 play Minecraft or Roblox in markets such as the United States, Canada, and Australia.

What’s more, these services are continually hitting new record highs (Roblox estimates it will hit 4B hours per month by 2023) and exhibiting incredible retention even as their users, the majority of whom are children, have exited and entered several life stages (e.g. tween, teen, young adult, independent adult). Consider, too, that the same game, Grand Theft Auto V, was the best-selling title of both the seventh generation of consoles (Xbox 360 and PS3, 2005-2013) and the eighth (Xbox One and PS4, 2013–2020), even though the tech/graphics/core gameplay didn’t change. This again is like a classic theme park ride. They remain popular long after they are no longer cutting edge, thanks to the fan’s enduring connection to and love for the experience.

Chapter Three: Explaining Unprecedented Popularity

The durability and scalability of these experiences are connected to why they’re so hard to define. To consider them a “game” is to consider iOS a phone, or Disneyland a specific Pirates of the Caribbean roller coaster. In truth, these “games” are a bundle of many, many different types of experiences that can appeal to every age group and satisfy nearly every mood. These can be fast-twitch interactive games or casually exploratory ones, about competition or about community, narratively-driven or non-narrative, finite or infinite, built specifically for millions of players or just for you, “professional” or rudimentary, R-rated or G-rated. And the “player” doesn’t need to choose between these. She can have all of them.

This is possible because the most important distinction between physical and digital theme parks isn’t the hours of operation, infinite capacity, or ability to disregard the second law of thermodynamics. Instead, it’s that these parks were designed to (or have since been converted to) allow for anyone to be an “Imagineer”. The developers of these titles aren’t trying to make a “game” but a “game engine” that allows everyone to create and share their own attraction.

Roblox and Minecraft, for example, are exclusively based on “creative modes” where users create experiences for themselves and others. There is no “game” made by the parent companies. While Fortnite is still mostly “Fortnite: Battle Royale”, it too has a burgeoning creative community that spans thousands of individual “worlds”. Grand Theft Auto, meanwhile, allows users to mod the “game” in any way they see fit — and even run custom, invite-only experiences on private servers. Most of developer Rockstar’s efforts today are focused on open experiences where users choose what they do, build, and with whom.

It is difficult to overestimate the incredible creativity that this model has unleashed. For example, nearly every game that could be recreated in Minecraft has been (e.g. Metroid). Corporations have built in-game cellphones capable of making live video calls to the real world using real world physics, users have built enormous explorable worlds based on existing IP (e.g. Game of Thrones' King's Landing, which is the size of Los Angeles) and new ones (one player spent 16 hours a day for a year building a 370 million block cyberpunk city). More recently, a community of Chinese Minecraft players rapidly re-created the 1.2MM square foot hospitals built in Wuhan following the COVID-19 outbreak in tribute to the “IRL” workers. There’s even an enormous education/school-based ecosystem built on Minecraft.

There are countless Grand Theft Auto user “mods” (albeit without license rights) that seamlessly transplant characters like Iron Man into the streets of Liberty City – which required coding capabilities (e.g. blaster-powered flight) that were never intended (let alone built) by the game’s developer, Rockstar. An enormous, GTA-specific community/game genre has emerged called “GTA Role-Play” in which cities/towns are created and players try out for (then adhere to) individual roles in this world (e.g. police officer, taxi driver or city planer). In some instances, these virtual worlds are based around a story (e.g. a murder mystery) and include role-playing rules (e.g. if you are killed investigating a crime, you must “forget” anything learned over the prior twenty minutes). But what matters here is more essential. Groups of players are building relatively mundane worlds where they take on fictional but conventional tasks and responsibilities, with people they don’t know, all for the sake of collective creation and immersion.

Fortnite, which is the earliest in building out its creation community, has seen everything from simple treasure hunts, to immersive mash-ups of the Brothers Grimm with parkour culture, and 10-hour sci-fi stories that span multiple dimensions and timelines.

Of course, most of these creations are mediocre and are never played. However, focusing on the raw, let alone average quality is to miss the point (for what it’s worth, 20% of Spotify’s library has never been played. The experiences users create don’t need to be “great” or polished to be popular (what makes GTA fun certainly isn’t its last-gen graphics or physics). These user created experiences also don’t need to be popular for their creators to take pleasure in the act of creation. And to this end, it’s important to recognize how expansive the creation process can be. Many games are run by a collective where individual participants are responsible for developing art, designing a world, managing the community, and so on. This sense of personal investment and shared ownership is profoundly sticky and meaningful.

Furthermore, there are enough experiences being produced overall that many of them are both great and popular (Billie Eilish and Drake get more Spotify streams than the 1980s). More than 50MM games have been made on Roblox Studio, of which 5,000 have had more than 1MM+ plays, 1,000 have hit 10,000 concurrent players, and 10 have had more than 1B plays (40MM toys have been sold, too). No one developer (e.g. Roblox Corporation) could ever have produced this offering internally — just as Apple could never have built a suite of proprietary apps as diverse, successful, and beloved as that of the iOS developer ecosystem overall. The fact that most of the community’s apps are “bad” or “unused” is irrelevant.

In this sense, these “digital theme parks” are really “digital theme park platforms”. Last year, Roblox paid out $100MM to developers (i.e. 1-20 person teams) against more than $500MM in UGC-based revenue. And in September, the company launched a “Marketplace” that allows developers to monetize not just their games, but also any assets, plug-ins, vehicles, 3D models, terrains, and items they made for it. This means developers can both reduce the time/effort required to create on Roblox, and receive additional revenue from the time/effort they invest. Roblox’s CEO David David Baszucki has said 75% of new hires work not on the game but on its underlying engine and tools.

The CEO of Epic Games, meanwhile, openly admits that its goal is to not care if the centrally-programmed “Fortnite: Battle Royale” dies. Instead, it wants the world to use Unreal Engine and/or Epic Online Services and/or Fortnite’s creation tools to independently design and operate anything they can imagine — even a better Fortnite. To this end, even Fortnite’s Creative Director Donald Mustard says that in the future he hopes that events like the live-in game Marshmello concert or the interactive “Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker” performance can happen entirely without him (notably, these two events represented engagement records for the game, too).

Chapter 4: Unlocking and Unlimiting Human Imagination

The value of the platform model isn’t new in consumer media. However, it does seem to be uniquely scalable in gaming, and it’s worth examining why.

As mentioned at the top of this essay, theme parks thrive because of our love for imaginary worlds. For decades, companies like Disney and Fox benefited from this desire by focusing on such stories and then selling toys and apparel that powered the imagination of fans. Consider, for example, the billions of hours American children spent imagining and acting out the adventures of Luke Skywalker and the Jedi with the 1970s and 1980s with figurines, robes, and lightsabers. However, this expansive imagination was forever trapped in brainwaves, backyards, and basements. It was hard enough to share these imaginary stories and world with close, in-person friends, let alone to faraway and unknown ones. And there was little Lucasfilm could do to access and leverage this imagination, either.

The gaps in solving these challenges were enormous: a “fan” needed years of training in game design, illustration, or writing, for example, and then they needed a way to distribute (and finance) their ideas. Worse still, these sorts of obsessions were generally looked down upon. In fact, most people judged a man building an expansive and detailed train set in the basement, or writing a detailed fanfic.

Today, it’s possible for the average fan to actually translate their imagination into a real, virtual space and then share it and play in it with their friends and world at large. And not only is it cool to do so, there are many companies designed around facilitating, promoting, and financially rewarding this behavior. This reflects an ongoing generational change in which younger audiences don’t just “consume” content, they “create” (YouTube, WattPad) and “remix” it (see TikTok, SoundCloud, Image Macros, etc.). This is particularly viable in gaming given the modular nature of the underlying content — e.g. assets, textures, maps, and so forth, as well as the fact that unlike a vlog or tweet, most gaming content is intended to keep expanding and be updated until it becomes a franchise.

This behavior also reflects an interesting pivot on a thesis that was widely held a decade ago: “in the future, everyone will know how to code". This thesis may yet play out, but it may instead be that the correct frame is, “in the future, everyone will create virtual worlds/games/experiences via icon/asset-based tools/engines." Consider, for example, that most of us didn't learn how to use MS DOS; the emergence of consumer Graphical User Interfaces and icon-based interactions meant we never needed to.

Furthermore, most people don’t need or want to “make” a website or app. Billions, however, do dream of fictional worlds and wish they could share them with their friends. Just as tens of millions spent decades wishing they could build their own Super Mario levels — and now millions do via Super Mario Maker, which is one of the ten best-selling “games” on the Nintendo Switch.

And as was the case with app platforms. The democratization of creation and distribution will have a profound impact on the identification and development of next-generation talent. We will see brand new studios emerge atop the platforms, just as King Digital and Rovio did on iOS and Android.

Chapter 5: Further Growth in Reach and Importance

These digital theme park platforms are already enormous. However, their scale and importance will only continue to grow in the years to come. Nearly every one of the underlying drivers behind these digital theme park platforms is growing: (1) their user bases; (2) the per user engagement; (3) the number and diversity of the experiences created by the community; (4) the ease with which a “player” can discover and jump from one experience to another; (5) the ease of creating an experience; (6) the technical and experiential capabilities of these engines/tools/experiences; (7) the ease and extent to which you can monetization individual creations (from individual assets to games); and (8) the importance of virtual worlds to the overall future of the Internet.

This trajectory speaks to the underlying moats of these digital theme park platforms, which, like physical theme parks, are diverse, deep, and durable. Most obviously, these digital theme park platforms own the overall customer relationship, billing, and all engagement data. But the core game engines are the most defensible; like the land and physical infrastructure of a park, they are built up over decades and impossible to fully short-cut. This includes not just enormous codebases, but years of enhancements to the end-to-end platform (e.g. core tech, tutorials, UI/X, community services) based on billions of hours of developer and consumer-side usage. This same engagement produces considerable stickiness; most creators are reluctant to use new engines/tools once they become proficient in one. Audiences, too, are sticky to existing behaviors and platforms that are already full of content and which include robust social graphs over new platforms with neither. This produces a virtuous cycle that means more content is created and better experiences are available to users, which brings in more users, stronger network effects, better monetization, and so on. As a result, success isn’t just about launching a more expansive suite of tools or greater ease of use. There’s a reason synthetic language like Esperanto and new keyboards like DVORAK haven’t taken off, after all, even though they’re demonstrably “better” than English and QWERTY.

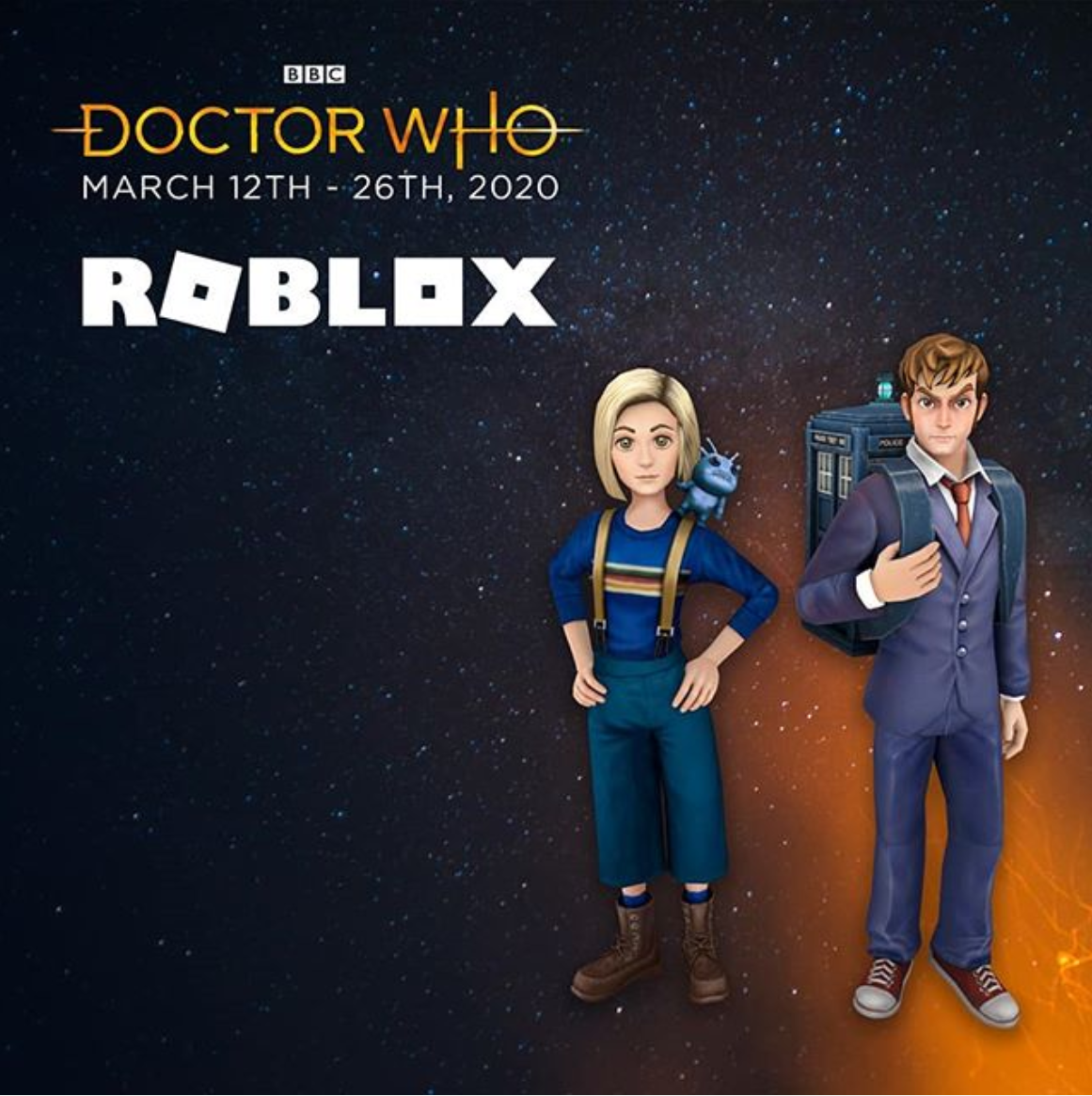

And just as Disney and Universal’s theme park moats enabled them to suck up third party IP like Nintendo, The Walking Dead, and The Simpsons, we’re seeing Fortnite, Minecraft, and Roblox do the same with an even more expansive set that includes DC, Marvel, Star Wars Universes, the NFL, John Wick, and Nike-Air Jordan. It’s likely that soon we’ll see D2C consumer product companies begin building their own bespoke experiences inside digital theme park platforms; the age of growth-hacking via referral codes, native podcast ads, SEO, and social is over. Imagine, for example, a Blade Runner-esque immersive world created by Harry’s. Similarly, we’re not far from albums premiering via “in-game” concerts attended by millions and which are set-up entirely by a label, rather than Roblox Corporation or Epic Games.

Chapter Six: Becoming a Real Digital Boy

So, what’s an IP owner or theme park operator to do? Two of the biggest digital theme park platforms are unacquirable. Minecraft was bought by Microsoft in 2014 for $2.5B (it has grown users nearly 4x since). It’s presently hard to imagine Fortnite being sold by Epic Games, or Epic Games being bought. Roblox and Grand Theft Auto could be purchased (though this would cost $6-15B).

The good news is more digital theme park platforms are likely to emerge. In February, for example, Sony unveiled its “Dreams” creation platform. It’s perhaps the most visually polished (would-be) digital theme park platform and includes many rich tutorials and is supported by even more proprietary, Dream-based experiences intend to inspire and demonstrate the enormous range of what’s possible. Less than a month later, “Core” was launched, too, which is essentially designed to be an easier-to-use creation platform that sits atop Epic Games’ Unreal Engine. The company has raised $45MM from a host of leading VCs. But although a new digital theme park platform is inevitable, the odds are low, the total opportunities are few, and the timelines long. In addition, it’s unclear how many platforms for UGC world creation are needed — just as most creators and consumers rely only YouTube or Twitch. Runners-up exist but are much, much smaller.

To Infinity and… Shutdown

Interestingly, Disney could have ended up with one of these platforms with its multi-franchise “open world” sandbox-style video game, “Disney Infinity”. The game first released in 2013, received widespread acclaim, and generated a reported $200-300MM in revenue over the first three years. Despite this topline, the game’s performance nevertheless fell short of Disney’s $1B internal target and, with that in mind, presumably well short of breakeven, too. It was cancelled in 2016.

However, this is probably more an example of “John Carter” than Disney’s ill-fated acquisition of Maker Studios — which is to say that the idea was broadly right but poorly executed. “John Carter” may have the modern record of the biggest theatrical bomb, but Disney’s strategy (and unprecedented success) is based on making enormous bets on classic (predominantly fantasy) IP that can be exploited across many mediums and ancillary products. “John Carter” was just the wrong IP, poorly adapted, and even more poorly managed.

Disney Infinity faced similar problems, many of which stemmed from Disney’s corporate culture but could have been overcome. For example, the game was originally designed to focus on individual characters and relatively fixed stories. In addition, monetization focused on $75 software sales, annual updates, and sales of affiliated, physical consumer products (known as “toys-to-life”). All very Disney decisions.

Over time, Disney Infinity did start moving towards a more open, creation-based system. However, it still required the “player” to be a “character”, not themselves. This agency problem is significant: imagine going to Disneyland and being told you can go where you like, but you have to dress up and behave as a different character as you moved between “theme lands”. Not only does this remove the specialness of being “you” in Disneyland and the ability to be hugged by your heroes, but it doesn’t really work. Regardless of whether you want to be Spider-Man in Disneyland, you can’t web sling through the park. And in Disney Infinity, you can web sling, but it doesn’t really make sense that Spider-Man is involved in urban planning. To return to an earlier point in the essay, too, it’s both boring and odd to play a game with all your friends and all be Spider-Man; if we’re all the same, we’re no one. There’s a reason why Fortnite, Roblox, and others are so focused on personalized emotes, aesthetics, and the preservation of individuality and/or agency. Almost all of the longest running games are based on either hyper-customizable characters or those without highly specific personalities.

Similarly, Disney Infinity’s initial “toy box” mode severely limited a player’s ability to build to their imagination. Instead of allowing players to build using core building blocks (i.e. voxels), users had to use essentially prefabricated set pieces that could only be used in specific ways. As a result, whole genres and experiences were impossible. This is where the theme park analogy starts to break for a physical parks operator. Disneyland is about tightly controlled experiences that are expertly designed to tell specific stories in specific ways. At Disneyland, attractions don’t open until they’re both complete, “perfect”, and predictable. There’s no real test, learn, change, repeat approach — especially compared to live, public experiments such as the Fortnite blackout. Hugs must be perfectly executed.

What makes Roblox and Minecraft so potent is their focus on tools above all else (there’s literally no story). The messiness and unpredictability of creation is not only most of the fun, but entirely user-led.

And thus, by the time the toys-to-life craze began to die, Disney Infinity found itself with a declining monetization model and a dwindling user base before it even had a chance to release “Disney Infinity 3.0”. Less than a year after this release, the game was cancelled.

Some of this was bad timing. When Disney Infinity began development (~2010), almost no one saw the potential digital theme park platforms (Minecraft didn’t launch until 2011, GTA Online in 2013, Fortnite in 2017) and those that did, such as Roblox (2006), were less than a hundredth of their present-day size. As a result, the “game” was built around entirely different and reasonable thesis: narratives, toy sales, high-priced annual updates. The “platform” play was a feature, a side-project.

At the same time, Disney Infinity could have worked in time. The most successful games require constant iteration and risk-taking, even where the future is unclear. To this end, Fortnite is a perfect example. Epic Games spent more than six years developing the game as the “Player versus Environment” title “Fortnite: Save the World”. It released to little fanfare and is barely played even today. It was only after Epic punted the title into an entirely new game format, the Battle Royale, that made the “game” into one of the most played, popular, and consequential games of the last decade. Many other examples of this trajectory exist. “No Man’s Sky” has succeeded by transforming from its original 2016 solo game into a live multiplayer game.

Beyond Infinity

Ultimately, every IP owner will need to figure out how to participate in digital theme parks and platforms — to figure out how to execute a digital version of the physical “hug”. This is especially true for those that don’t even have physical theme parks and for which the alternative — building one — would take more than a decade and $20B+ in capital. Even then, each individual park would still reach only ten or so million fans per year and those fans would be concentrated in a specific geography. And even if you already own a park, the opportunities to integrate/interplay with a digital one is enormous – especially as films begin to use game engines to render their CGI environments.

But while there’s obviously value in owning one of these digital theme park platforms, it’s not clear a major IP needs to. When the Disney’s Parks & Resorts business unit licensed the theme park rights to Avatar from Fox, it was to design, operate and control nearly everything about “Pandora — The World of Avatar” — from how it looked, to where it was, how many people could use it, how much it cost and which account systems were used to buy a pass (hint: Disney’s). Minecraft, Fortnite, and Roblox don’t want to take on these responsibilities. Instead, they explicitly want IP owners to take on the greatest possible role in building and operating their own digital parks using their engines. To this end, Disney or Universal or Warner Bros should be building their own Fortnite-based Islands or Minecraft worlds.

And this is precisely what IP companies are uniquely great at.

Consider, for example, the following description of Walt Disney’s “four levels of details” from “One Little Spark!: Mickey's Ten Commandments and the Road to Imagineering”, written by former Principal Creative Executive at Disney Parks & Resorts, Marty Sklar:

“Detail level one is when you are standing out in the countryside and see the church steeple sticking up above the trees. Detail level two is when you enter town and are looking down the street. You can see the street, the median, the parkway strips, sidewalks, and trees. Detail level three is when you are standing on the sidewalk looking at one of the houses. You can see the character of the house, walls, roof, windows, trim, and doors. Detail level four is when you have actually walked up to the front door, grabbed the door knocker, see its detail, finish, and feel its temperature and weight as you knock on the door… most architects are pretty good at getting to level three, but here at Disney we must always get to the detail level four so we can maintain our immersive environments that our stories create”.

This quote speaks to the enormous cultural advantage and capability held by companies like Disney or Universal when it comes to building digital immersive worlds. At the same time, it also explains why they’ve struggled with experimentation and creation-oriented content/platforms. In addition, it is much, much harder to operate a robust cross-platform engine, marketplace, and UGC toolkit than it is to deliver ingested, pre-recorded (and often cached-at-local-node) video content over Internet (i.e. SVOD). This simply isn’t a skillset any media company has today.

As a result, it’s sensible (today) that such companies would leverage the existing engines, tools and marketplaces of a third party and focus all of their efforts on designing and operating an expansive digital park (v platform). Again, it’d be better if a Disney, Universal or WarnerMedia could own the full digital theme park platform stack. However, the alternative (and status quo) is to hand over everything, from creative to customer data, to a third party — or not have a park altogether.

In addition, there are different ways to manage platform reliance. Disney, for example, could build an adjacent island theme park inside the Fortnite universe. Or, it could just use Epic Games’ Unreal engine (as many developers do, including Nintendo, as well as Disney’s own filmmakers) and then selectively use Epic Online Services to operate the “park” while also connecting into Disney’s own account and billing systems.

It is easy to say, “we can’t do it”, “we’ve tried and failed”, or “what even is the roadmap here”. These are fair and important rejoinders. However, as the “Imagineering Story” frequently reiterates, nobody at Disney had built a theme park, or had any relevant experience (other than narrative) before Walt insisted they do it. And it was messy, and uncertain, and chaotic, with the business folks (which I say with love as I am one) who were terrified of the cost, skeptical of the demand and long-term interest, and rattled by the lack of a clear business case. Note, too, that today’s leading platforms will, themselves admit they hardly know what they’re doing — and how can they? But of course, it helps when you can grow by letting your most imaginative and obsessive fans chip in.

Matthew Ball (@ballmatthew)