Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

A couple of weeks ago, I came across a really interesting career advice article from Derek Thompson. There are few writers who continue to produce banger after banger, and Derek is one of them. When he writes something, I read it.

Most career advice posts lie somewhere between cringe and cliché. This one isn't most career advice posts. Thompson gave five excellent pieces of career advice, but point three really stood out:

Don’t do the job you want to tell other people you do. Do the job you want to do.

A quote from his article:

Many years ago, I was thinking about taking a job at another company with a fancy-sounding title that belied the drudgery of the underlying work. (By the way, beware this inverse relationship, as sometimes the most attractive titles are reserved for the most soul-destroying labor.)

I told my colleague James Fallows, then a writer at The Atlantic, how excited I was to tell people at parties about this new job title that I would soon carry around, like a boutonniere on my lapel. “Don’t do the job you want to tell people you do,” he said. “Do the job you want to do.” Well, damn, I replied. And that was that. I turned down the position about five minutes later.

Derek Thompson

The dichotomy of work: the job you want to tell other people you do vs. the job that you want to do.

Since we were kids, we've been told to do what we want to do. To follow our dreams. The thing is, no one really meant it when they told us to follow our dreams. These "dreams" were meant to serve as vague undefined targets, not precise, actionable goals.

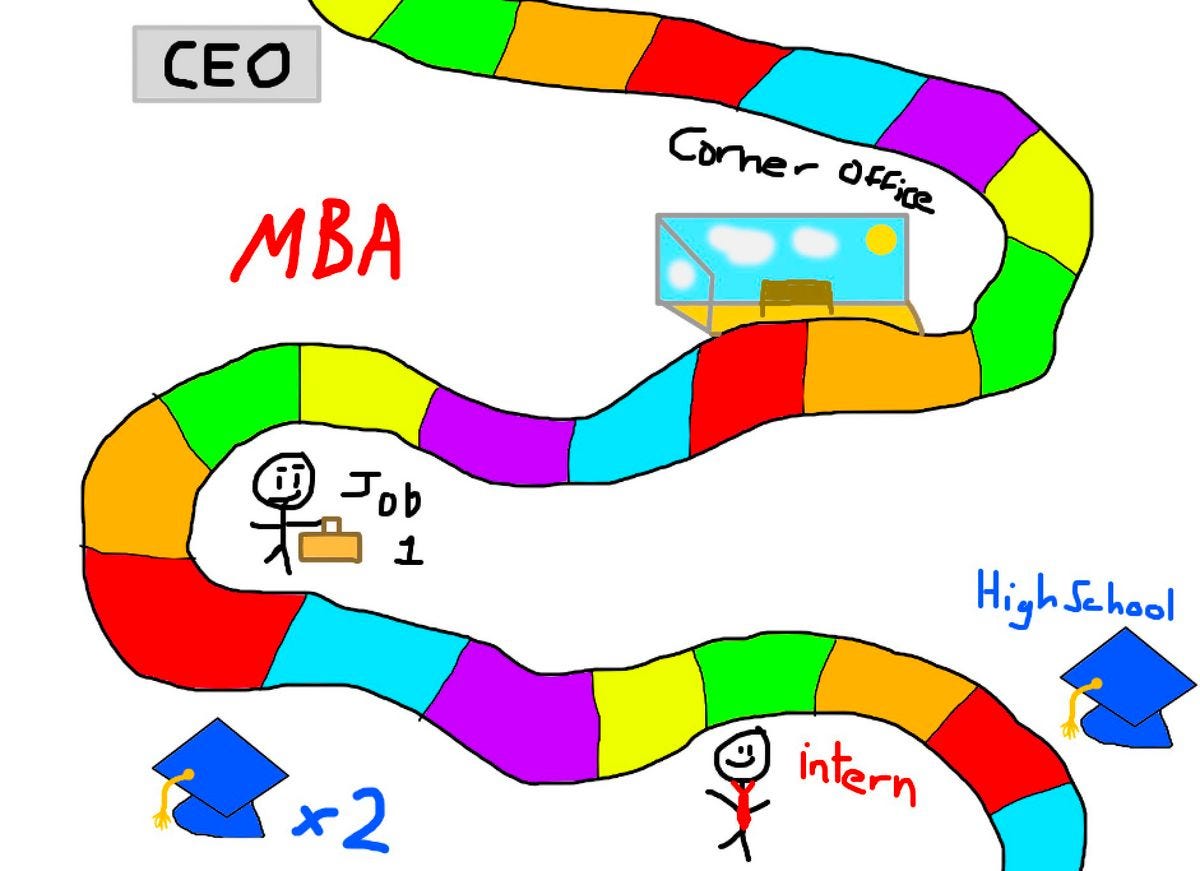

We might be told to follow our dreams, but we are taught to pursue practicality. To do "what we're supposed to do." To win the game, and the game goes something like this:

Get good grades in high school to get into a good college to get a good job with a good salary to get promoted to a better job with a better salary. Maybe we go to graduate school or attend different training programs to make us more attractive employees.

The game continues as we climb the corporate ladder. More money. More prestige. More responsibility. This game doesn't have time for your "dreams". When you are playing the game, the logic behind every single decision we make is simple: Will this help me advance in this "game"?

This game makes for an easy measuring stick, because every single one of us is taught to play it. And the jobs that we want to tell other people that we do? The high paying jobs? The prestigious jobs? They are placed on a pedestal, and they are only accessible to those who are really good at this game.

These jobs provide the ultimate signaling mechanism, because they signify who is winning the game. Of course, the Venn diagram between the jobs that we want to tell other people that we do and the jobs that we actually want to do is often two separate circles. As Derek said, "Sometimes the most attractive titles are reserved for the most soul-destroying labor."

However, this game leaves us with no room to think about whether or not we actually like what we're doing, so we rarely stop to consider whether or not we want to be playing this game in the first place.

But every once-in-a-while, a thought materializes in the recesses of our minds: Is this really what I want to do for the next 40 years?

(A word of advice, if that thought has ever entered your mind, the answer is always "No.")

And that's when the identity crisis hits. So how do we reconcile our newfound lack of confidence in our career choices with the foundational beliefs that led us to make these choices in the first place?

Through compromise.

"I'm just doing _______ for a couple of years until I figure out what I want to do."

"I want to do my own thing, but it's too risky right now."

Different ways of saying, "I'll follow my dreams after doing this other thing a little bit longer."

(Now don't get me wrong, this *can* work. Some people really do go into a difficult but high-paying job with the plan of grinding hard for a few years to make as much money as possible as quickly as possible so they can escape the grind financially secure later. But that's the exception, not the rule. The difference between executing a well-thought-out plan and simply appeasing our current situation is night and day.)

Rolf Potts's Vagabonding is one of the few books that I have reread multiple times, and one story from Chapter 2 is permanently etched in my memory:

“There’s a story that comes from the tradition of the Desert Fathers, an order of Christian monks who lived in the wastelands of Egypt about seventeen hundred years ago. In the tale, a couple of monks named Theodore and Lucius shared the acute desire to go out and see the world.Since they’d made vows of contemplation, however, this was not something they were allowed to do. So, to satiate their wanderlust, Theodore and Lucius learned to “mock their temptations” by relegating their travels to the future. When the summertime came, they said to each other, “We will leave in the winter.” When the winter came, they said, “We will leave in the summer.”They went on like this for over fifty years, never once leaving the monastery or breaking their vows. Most of us, of course, have never taken such vows—but we choose to live like monks anyway, rooting ourselves to a home or a career and using the future as a kind of phony ritual that justifies the present. In this way, we end up spending (as Thoreau put it) “the best part of one’s life earning money in order to enjoy a questionable liberty during the least valuable part of it.”We’d love to drop all and explore the world outside, we tell ourselves, but the time never seems right. Thus, given an unlimited amount of choices, we make none. Settling into our lives, we get so obsessed with holding on to our domestic certainties that we forget why we desired them in the first place.

Rolf Potts, Vagabonding

The monks delaying their travels? They are every single one of us every time we use the idea of a vague, undefined, "better" future to pacify our current circumstances.

And we can play this game for years. We can always find a reason to tell ourselves "the time just isn't right!" And if we tell ourselves this story long enough, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. We never get around to doing those things that we want to do.

Warren Buffett is full of sage advice, so it's no surprise that he has commented on this very topic.

I was up at Harvard a while back, and a very nice young guy, he picked me up at the airport, a Harvard Business School attendee. And he said, "Look. I went to undergrad here, and then I worked for X and Y and Z, and now I've come here." And he said, "I thought it would really round out my résumé perfectly if I went to work now for a big management consulting firm." And I said, "Well, is that what you want to do?" And he said, "No," but he said, "That's the perfect résumé." And I said, "Well when are you going to start doing what you like?" And he said, "Well I'll get to that someday." And I said, "Well you know, your plan sounds to me a lot like saving up sex for your old age. It just doesn't make a lot of sense."

Warren Buffett

"I need more money/experience/whatever before I can quit my job to pursue something that I actually like," you think. "A few more years will give me more freedom to pursue *that thing*, whatever *that thing* is."

That's the story we tell ourselves, but that story rarely aligns with reality. Here's the reality of waiting "a few more years."

You will get a promotion or accept a new job offer that leads to a higher income, and your spending habits will likely inflate with the additional cash.

You will take on more responsibilities at work as your career progresses, making it more difficult to walk away.

The odds of you getting married/buying a house/having kids/taking on larger personal responsibilities increases exponentially.

So yes, while objectively you will likely have more money in a few years, you will also most likely have a more expensive lifestyle, more career responsibilities, and more personal obligations. And no matter how much you like or dislike your job, it is now harder than ever to walk away.

The window for many opportunities is shorter than you think.

A controversial opinion of mine, but I believe that spending years doing something that you hate to eventually make enough money to do something that you like is just procrastination disguised as ambition.

The truth is, if you have a thing that you want to pursue, you need to pursue it. Doubly so if you are currently spending your days doing work that you actively loathe.

Pursuing something new might mean quitting your job entirely, or you could simply start by investing time into something new after work and on weekends. You certainly don't have to go full-send and resign on Day 1. But the idea that you can't start working on what you actually want to do until you have spent an arbitrary amount of time doing stuff that you don't want to is just categorically false.

Real life isn't school. There aren't any prerequisites you have to complete to chase the fun stuff. Don't use ambition as a veil for your procrastination. As Buffett said, you wouldn't wait til you were 80 to have sex, would you?

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!