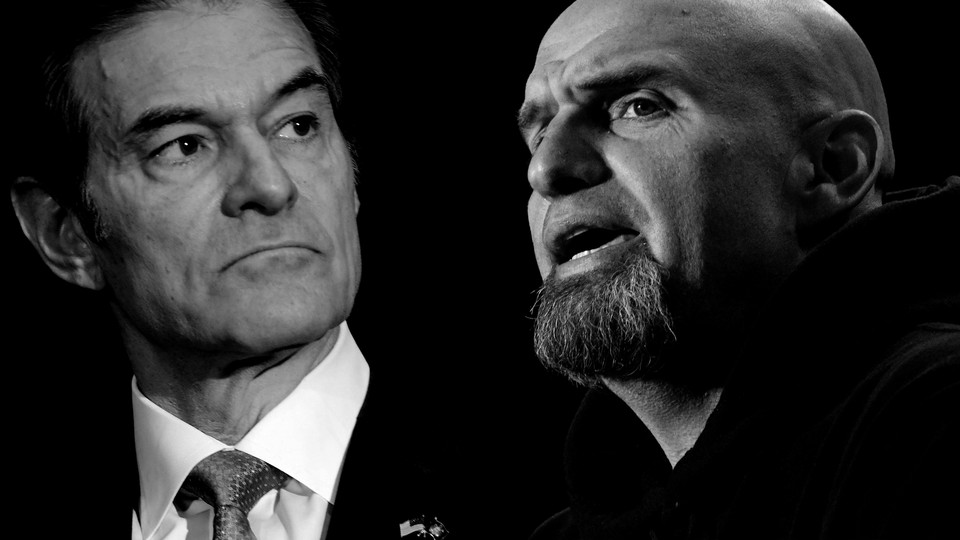

The Fetterman-Oz Debate Was a Rorschach Test

The Democratic nominee for Senate has no choice but to bet on Pennsylvania voters identifying with his health struggles instead of viewing them as disqualifying.

Why did John Fetterman’s team agree to tonight’s debate? Because declining it likely seemed a worse option. For all of Mehmet Oz’s carpetbaggery, medical quackery, and general charlatanism, he got that much right near the end of the first and only Pennsylvania debate for U.S. Senate: Voters really do want to see both candidates face off.

Fetterman used to talk one way, he had a stroke, and now he talks another way. In certain post-stroke interviews, with the help of captions and in the absence of a ticking clock, he has given strong answers to reporters and battled speculation about his overall unfitness to serve. Tonight, as debate moderators reminded each candidate of strict time parameters (“60 seconds,” “30 seconds,” “15 seconds”) Fetterman prioritized speed over lucidity, and his disjointed sentences made his struggles unmistakable. This evening, Fetterman may have lost whatever swing voters are left in Pennsylvania. And yet, he may have won over some voters who watched a man recovering from a stroke stumble through sentences on live TV and came away admiring his courage for debating at all.

Tonight’s hour-long exchange was, in some ways, a Rorschach test of comfort with disability. Viewers from outside Pennsylvania tuned in to the broadcast from a local TV studio in Harrisburg to hear the candidates discuss the defining issues of this election cycle—abortion, inflation, gun laws, illegal immigration, energy—but many people queued up the livestream to gawk at one of the candidates. Unfortunately, no disability accommodations—not even 70-inch television monitors for real-time captioning—can change how our society stigmatizes verbal disfluency. We are a culture of sound bites, mic drops, and clapbacks. To speak in any way that deviates from the norm is to summon ridicule and judgment. That’s already happening to Fetterman, and his campaign now faces an extraordinarily difficult situation.

Fetterman relied on three main strategies in his attempt to quell the nerves of anxious viewers, with intermittent success. He kept his answers short, often too short, sometimes skipping over conjunctions, prepositions, and other words that weave sentences together. He seemed to be overly aware of the clock and aggressively evaded the “time’s up” bell on nearly every topic and rebuttal. He employed the phrase “I believe” as both a way to be seen as speaking from his heart and, perhaps, to allow himself a couple of extra seconds to craft a response. He skillfully deployed a few zingers that reminded voters of his summer-long social-media trolling campaign premised on the idea that Oz doesn’t really reside in Pennsylvania. “Why don’t you pretend you live in Vermont and run against Bernie Sanders?” he asked at one point.

Notably, Fetterman failed (or declined) to answer some key questions and follow-ups. When asked directly about his contradictory statements on the issue of hydraulic fracking, he simply said, “I absolutely support fracking,” without elaborating as to how or why he changed his position. Oz, for his part, dodged multiple simple, direct questions on issues such as where he stands on legislation to raise the minimum wage and how he’d vote on a gun-reform bill.

Oz knew he had the advantage and spent most of the night trying to swallow a smirk. A broad smile finally spread across his face just after the 45-minute mark as Fetterman struggled through an answer. All night, Oz took subtle shots at Fetterman’s health and mental acuity. He called Fetterman’s television ads “a fiction of his imagination” and spoke of “fables” that his opponent believes. “John Fetterman’s approach to health is a very dangerous one,” Oz said, in an answer to a question about health policy that sounded more like a discussion of his opponent’s challenges. As the night went on, he got less subtle: “John, obviously I wasn’t clear enough for you to understand this,” he said.

Oz proved a smooth operator, if not a good-faith one. He looked directly into the camera, spoke for uninterrupted stretches, and wore a well-tailored suit. He talked with his hands, like the seasoned politician he’s not, and made emotional appeals to elderly voters, marketing himself as a trustworthy doctor who listens. He also repeatedly labeled Fetterman “extreme.” He closed by calling himself “the candidate for change,” an interesting approach for a conservative.

Fetterman, who wore a suit and a tie tonight, looks a tad unnatural in anything but his Carhartt sweatshirt, a fact that has been core to his appeal. He has acknowledged difficulties in his stroke recovery, but tonight he refused to commit to releasing his detailed medical records. As a result, voters lack a complete understanding of how the stroke may have affected him. It’s reasonable—essential, even—for the public to ask questions and expect transparency after a major medical event. Transparency, Fetterman countered, would come in the form of him being onstage to compete at all.

Two weeks from now, some number of voters will agree with that idea, yet others are likely to feel uncomfortable voting for a person who does not comport with their notion of what a politician sounds like. Fetterman’s campaign had no good options going into tonight, and seemed to know it, going so far as to send out a memo to reporters telegraphing an Oz victory before the debate had even started. In the final weeks of the race, Fetterman will continue to try to sell voters on his character, and on the importance of sending a Democrat to the Senate. But after tonight, he may no longer have a choice but to be more forthcoming about the medical challenges he faces—and to place his faith in Pennsylvania voters identifying with his struggles instead of viewing them as disqualifying.