What do you think?

Rate this book

976 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1955

– He invited me there, in fact, to see the mummy. He had made one himself for me! Oh, but with such ingenuity, it was really a masterpiece…

– Really, my dear fellow…

– I confess I did not have heart to finish our business so immediately, I spent a few minutes congratulating him. He became very angry when I appeared to question the… authenticity? of this thing, but he was very proud. I saw in his eyes, he was very proud, when we finished our business together.

What greater comfort does time afford, than the objects of terror re-encountered, and their fraudulence exposed in the flash of reason?

How real is any of the past, being every moment revalued to make the present possible?

The what? The Recognitions ? No, it's Clement of Rome. Mostly talk, talk, talk. The young man's deepest concern is for the immortality of his soul, he goes to Egypt to find the magicians and learn their secrets. It's been referred to as the first Christian novel. What? Yes, it's really the beginning of the whole Faust legend…What can drive anyone to write novel...?

What writing is all about is what happens on the page between the reader and the page . . . What I want is a collaboration, really, with the reader on the page where the reader is also making an effort, is putting something of himself into it in the way of understanding, in the way of helping to construct the fiction that I am giving him. - William Gaddis, Albany, April 4, 1990

Eliot and Dostoyevski are the most significant names here; none of Gaddis's reviewers described The Recognitions as The Waste Land rewritten by Dostoyevski (with additional dialogue by Ronald Firbank), but that would be a more accurate description than the Ulysses parallel so many of them harped upon. Not only do Gaddis's novels contain dozens of "whole lines lifted bodily from Eliot," but The Recognitions can be read as an epic sermon using The Waste Land as its text. The novel employs the same techniques of reference, allusion, collage, multiple perspective, and contrasting voices; the same kinds of fire and water imagery drawn from religion and myth; and both call for the same kinds of artistic, moral, and religious sensibilities.

...Life proved terrible enough by the 1950s to produce in The Recognitions the most "Russian" novel in American literature. Gaddis's love for nineteenth-century Russian literature in general crops up in his novels, his letters, and in his few lectures, where references are made to the major works of Dostoyevski, Tolstoy (especially the plays), Gogol, Turgenev, Gorky, Goncharov, and Chekhov. Gaddis shares with these authors not only their metaphysical concerns and often bizarre sense of humor, but their nationalistic impulses as well. - William Gaddis by Steven Moore

That romantic disease, originality, all around we see originality of incompetent idiots, they could draw nothing, paint nothing, just so the mess they make is original...Even two hundred years ago who wanted to be original, to be original was to admit that you could not do a thing the right way, so you could only do it your own way. When you paint you do not try to be original, only you think about your work, how to make it better, so you copy masters, only masters, for with each copy of a copy the form degenerates...you do not invent shapes, you know them, atiswendig wissen Sie, by heart...

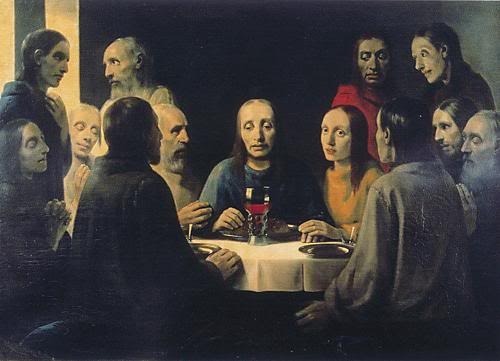

This...these...the art historians and the critics talking about every object and...everything having its own form and density and ...its own character in Flemish paintings, but is that all there is to it? Do you know why everything does? Because they found God everywhere. There was nothing God did not watch over, nothing, and so this...and so in the painting every detail reflects...God's concern with the most insignificant objects in life, with everything, because God did not relax for an instant then, and neither could the painter then. Do you get the perspective in this? he demanded, thrusting the rumpled reproduction before them. -There isn't any. There isn't any single perspective, like the camera eye, the one we all look through now and call it realism, there...I take five or six or ten...the Flemish painter took twenty perspectives if he wished, and even in a small painting you can't include it all in your single vision, your one miserable pair of eyes, like you can a photograph, like you can painting when it...Like everything today is conscious of being looked at, looked at by something else but not by God, and that's the only way anything can have its own form and its own character, and...and shape and smell, being looked at by God.

Yes, I remember your little talk, your insane upside-down apology for these pictures, every figure and every object with its own presence, its own consciousness because it was being looked at by God! Do you know what it was? What it really was? that everything was so afraid, so uncertain God saw it, that it insisted its vanity on His eyes? Fear, fear, pessimism and fear and depression everywhere, the way it is today, that's why your pictures are so cluttered with detail, this terror of emptiness, this absolute terror of space. Because maybe God isn't watching. Maybe he doesn't see. Oh, this pious cult of the Middle Ages! Being looked at by God! Is there a moment of faith in any of their work, in one centimeter of canvas? or is it vanity and fear, the same decadence that surrounds us now. A profound mistrust in God, and they need every idea out where they can see it, where they can get their hands on it. Your...detail, he commenced to falter a little,- your Bouts, was there ever a worse bourgeois than your Dierick Bouts? and his damned details? Talk to me of separate consciousness, being looked at by God, and then swear by all that's ugly!

Crémer's shrug still hung in his shoulders, and he emphasized it with a twitch, throwing the exact lines of his neat blue suit off, for it was a thing of careful French construction, and fit only when the figure inside it was apathetically erect, arms hung at the sides, at which choice moment the coat stood up neat and square as a box, and the trousers did not billow as they did in walking, but hung in wide envelopes with all the elegance that right angles confer, until they broke over the shoes, which they were, fortunately, almost wide enough at the bottoms, and enough too long, to cover.

It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents - except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.

Images surround us; cavorting broadcast in the minds of others, we wear the motley tailored by their bad digestions, the shame and failure, plague pandemics and private indecencies, unpaid bills, and animal ecstasies remembered in hospital beds, our worst deeds and best intentions will not stay still, scolding, mocking, or merely chattering they assail each other, shocked at recognition.Shocked, surprised and mesmerized by these Recognitions. Sometimes reading of a book happens without any noticeable event while other times, a single sentence affords the brilliance of a memorable experience. The perceptible sameness of things stimulates an unalterable change, a connection emerges out of nowhere and the voice of a stranger becomes familiar and captivating since it seems to carry the virtues and vices of the whole wide universe within it. This all happened for me after reading Gaddis’s tour-de-force and I can vouch for the same simply because:

The lust of summer gone, the sun made its visits shorter and more uncertain, appearing to the city with that discomfited reserve, that sense of duty of the lover who no longer loves.Wherever Gaddis took me, he offered the sublime company of warm rays and bright moonlight and during the instances of foggy days; I relished the unusual beauty of a silent landscape. I walked.

Overlong? Probably. Grandiose? Almost certainly. Brilliant? Most definitely. This swollen, acerbic cult classic bursts with such wild imagination, vivid characterization and profound eloquence that I couldn't help but love it. Its many characters swirl in and out of each other's lives throughout the nearly thousand-page text, their paths and conversations overlapping like a most rambunctious Altman ensemble film (though with Gaddis's relentless and sometimes hallucinatory skewering of organized religion and the bourgeoisie, it might seem closer to a Buñuel satire).

The novel is a literary triptych, divided into three distinct segments that focus on various forms of art and forgery, and the perpetually blurred line between reality and illusion (not to mention the poisonous relationship between art and capitalism). The art world is not the only subject to be impaled upon Gaddis's eviscerating pen: the realms of business, politics, and religion also get their fair share of (often well-deserved) scorn and cynicism. The book's second and largest segment, set mostly in a feverish, forbidding vision of New York City, hinges together the smaller outer segments which mirror each other in many ways. Within this framework the reader enters a social whirlwind containing sinister art dealers, eccentric writers, struggling musicians, corrupt clergymen, con artists, counterfeiters, advertising agents, hitmen, WASPs, bohemians, transvestites, desperate housewives, and so forth, as they talk, travel, eavesdrop, cheat, steal, murder and deceive their ways through their pointless days. Gaddis captures a culture of people too self-absorbed to perceive any sort of higher truth, and too emotionally atrophied to form meaningful connections with others. While the obsessive artists yearn to transcend modern humanity with their works, everyone else sinks deeper into a fog of fraud and miscommunication. The transatlantic voyage that many of the characters take in Part III dispels this fog for some, but thickens it for others, as the novel builds toward its tragic yet strangely triumphant conclusion.

The Recognitions is remarkably dense and erudite; Gaddis has a striking way of intertwining historical, artistic, literary, theological and mythological arcana and symbolism with his descriptions, crafting multilayered allusions that resonate throughout the text and across centuries of human thought and creation. When he succeeds at this, it is stunning. When it seems a little strained, well, it's still educational. Readers flustered by his range of esoteric knowledge can still find much to admire elsewhere; his sardonic sense of humor will appeal to a certain audience, and his often breathtaking writing skills will appeal to anyone who loves language. So, whether or not this fiery novel is truly the missing link between literary modernism and postmodernism, it simply must be experienced on its own terms — even when it threatens to collapse under the weight of its own obese ambitions.

What I get a kick out of is serious writers who write a book where they say money gives a false significance to art, and then they raise hell when their book doesn’t make any money.

- William Gaddis, The Recognitions

In that undawned light the solid granite benches were commensurably sized and wrought to appear as the unburied caskets of children. Behind them the trees stood leafless, waiting for life, but as yet coldly exposed in their differences, waiting formally arranged, like the moment of silence when one enters a party of people abruptly turned, holding their glasses at attention, a party of people all the wrong size. There, balanced upon pedestals, thrusting their own weight against the weight of time never yielded to nor beaten off but absorbed in the chipped vacancies, the weathering, the negligent unbending of white stone, waited figures of the unlaid past.

Directly he was alone, he was assailed by her simulacra, in all states of acute sorrow, or smiling, of complete abstraction or painful animation, of dress and undress, as he had seen her these last few days: directly he was alone, the images came to mock everything he had seen. Her sadness became shrieking grief, and her animation riotous, immodest in dress and licentious in nakedness, many-limbed as some wild avatar of the Hindu cosmology assaulting the days he spent copying his work on clean scores, and the nights he passed alone in his chair where, instantly the lights went out, everything was transformed, and the body he had seen a moment before with no more surprise than its simple lines and modest unself-conscious movement permitted, rose up on him full-breasted and vaunting the belly, limbs indistinguishable until he was brought down between them and stifled in moist collapse.

Over and under the ground he hurried toward the place where he lived. No fragment of time nor space anywhere was wasted, every instant and every cubic centimeter crowded crushing outward upon the next with the concentrated activity of a continent spending itself upon a rock island, made a world to itself where no present existed. Each minute and each cubic inch was hurled against that which would follow, measured in terms of it, dictating a future as inevitable as the past, coined upon eight million counterfeits who moved with the plumbing weight of lead coated with the frenzied hope of quicksilver, protecting at every pass the cherished falsity of their milled edges against the threat of hardness in their neighbors as they were rung together, fallen from the Hand they feared but could no longer name, upon the pitiless table stretching all about them, tumbling there in all the desperate variety of which counterfeit is capable, from the perfect alloy recast under weight to the thudding heaviness of lead, and the thinly coated brittle terror of glass.

'The sky was perfectly clear. It was a rare, explicit clarity, to sanction revelation. People looked up; finding nothing, they rescued their senses from exile, and looked down again'

That romantic disease, originality, all around we see originality of incompetent idiots, they could draw nothing, paint nothing, just so the mess they make is original . . . Even two hundred years ago who wanted to be original, to be original was to admit that you could not do a thing the right way, so you could only do it your own way. When you paint you do not try to be original, only you think about your work, how to make it better, so you copy masters, only masters, for with each copy of a copy the form degenerates . . . you do not invent shapes, you know them.

—His work is so good it has almost been taken for forgery.

—What do you mean by that?

—By the lesser authorities, of course. The ones who look at paintings with twentieth-century eyes. Styles change, he mused, (…) most forgeries last only a few generations, because they’re so carefully done in the taste of the period, a forged Rembrandt, for instance, confirms everything that that period sees in Rembrandt. Taste and style change, and the forgery is painfully obvious, dated, because the new period has discovered Rembrandt all over again, and of course discovered him to be quite different. That is the curse that any genuine article must endure.

You know, Brown, if by any stretch of imagination I could accuse you of being literary, I might accuse you of sponsoring this illusion that one comes to grips with reality only through the commission of evil.

—He even said once, that the saints were counterfeits of Christ, and that Christ was a counterfeit of God.

—Damn it, it isn’t, it isn’t. It’s a question of . . . it’s being surrounded by people who don’t have any sense of . . . no sense that what they’re doing means anything. Don’t you understand that? That there’s any sense of necessity about their work, that it has to be done, that it’s theirs. And if they feel that way how can they see anything necessary in anyone else’s? And it . . . every work of art is a work of perfect necessity.

There was Arthur, with a beard, who was writing a new life of Christ, to be published under another name, the same name he had used when he reviewed his first book, published under his own name, a satire on the Bible so badly received that he joined the chorus of its detractors.