What do you think?

Rate this book

64 pages, ebook

First published January 14, 2011

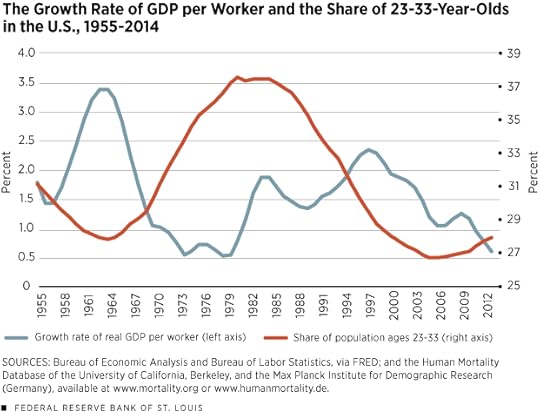

What is critical is the theory that young workers have relatively low human capital and that, as they become older, they accumulate human capital. ... The U.S. birth rate peaked circa 1960, implying a large share of people in their 20s circa 1980. ... It is important to realize that, should the theory proposed here be correct, there exists a sense in which the productivity slowdowns (especially in the 1970s) are statistical artifacts, that is, it may be that the productivity of individual workers did not change at all during the 1970s, but that the change in the composition of the labor force caused the slowdown in labor productivity.

As late as the mid-1990s, medical literature reported less than two hundred cases, and only three of those were people born with it - so few some researchers expressed an opinion that one could not be born with it. ... Well, in the spring of 2006, two tests made upon random samples from general populations were finally given, and they revealed a very surprising number: About two percent of the population is face blind!