Chapter 1: Green-Shaming no More

A Short Story About Bananas & Wine

After approximately 15 long years of trying, I finally cracked the code. Maybe the timeline could be attributed to too many distractions and a lack of focus; surely the timeline was due to me not having enough knowledge when I began. Regardless though, I now have done it. I think I finally have found a solution, all by identifying the root cause of the following problem:

Why aren’t we, collectively, able to address the climate emergency? Even at the margin?

We do all generally agree on an over-arching theme, though; we agree on the importance of protecting and improving the environment in which we live. Yet, so little is done. The work that is done is done too slowly, and not always where it matters most. 30 years of COP conferences, UNFCC frameworks, failed public programs, failed policies, conflicts of interests, VIPs, and politicians fighting climate change from their private jets; the list goes on. What a sh*t show! It’s just not working. Just an example: The World Bank recently shared an article about gas flaring impacts (the burning of natural gas associated with oil extraction)

“Efforts to reduce global gas flaring volumes have stalled over the last decade. Significant progress in some countries has not offset flaring increases in others.”, 2022.

After reading that, I was reminded of the big question I posed at the beginning. With so much science, and so many combined skills and technologies all fighting the same enemy; we still are not making an impact. Why?

On top of taking a personal interest in the matter, I was professionally involved in the sector when this all started as well, having spent 6 years in the energy, climate change and impact mitigation field. In 2014, I made the decision to leave that career path. Six years for what? I could not continue to “piss into the wind” (pardon my French). I needed a drastic change both of career and focus, for my mental health.

2008 and my ‘Collision’ with the Macroworld

To be precise, it was actually September 15, 2008. Financial giant Lehman Brothers had just filed for bankruptcy and I had just signed my first job contract, so that day lives in my memory well. Not because I had just started my career, but because the event sparked my desire to learn what exactly had just taken place.

The economic prospects started to shrink very quickly in the world and around me. Foreclosures in the US were causing ripple effects in the banking system throughout the world. As is human nature, we see crisis and then the amygdala kicks in. Like millions of other people, I started to wonder what would come next and if it would have any impact on me. To learn what was coming, I looked back and dove head first into researching what caused the Lehman collapse.

In 2008, I graduated college as an engineer. That said, terms like “CDS”, “subprimes”, and “foreclosures” were not exactly familiar jargon. In the newspaper, banks were declared “too-big-to-fail”. Central banks started to print money to protect them from certain death through contagion. This raised eyebrows and my curiosity. Printing money? How can central banks print money? Is it not backed by something like gold? Can they print money out of thin air? And most importantly, what is money?

So many questions flying around my mind, and too little structure or knowledge in place for me to address them properly. So I studied, alone. I started my journeys in both the money & macroworld that year, and I’ve continued to study and grow in those fields through present day.

Fast Forward to 2022

No Progress on the Climate front

8 years after leaving my “I wanna save the world” consultant job (naive in hindsight), not much has changed for climate change.

Greenhouse gas emissions have never been so high, and the G20 continues to argue about the best way(s) to change course.

The global order is in shambles following the invasion of Ukraine by Russia. The chances of getting soon a global agreement on Climate Change have almost reduced to zero in 2022.

Europe’s Energy Crisis

While globally there is no improvement on the climate front to speak of, we cannot argue the fact that some countries have stepped up to make a difference. Let’s focus on Europe for a moment. The European green agenda has been very active over the last two decades. But today, it has become obvious to everyone that these policies have gone too far compared to their negligible impact, and the risks taken.

The energy crisis reveals in broad daylight that 1) energy is a national security topic and 2) renewable energy sources are not yet able to replace reliable base-load power. Unfortunately, when looking ahead, Europe is severely lacking in investments for base-load capacities in the years to come. Europe’s energy security has been sacrificed at the expense of the climate agenda. More renewables = more gas to dispatch energy when the sun goes down, or when the wind slows. By the end of 2020, The European Union 27 sourced almost 40% (!) of their imported natural gas from Russia; consequences of that dependency rearing their ugly head in the wake of the Ukraine invasion. A less visible issue currently, but one to still note, is that Europe created new external dependency; sourcing 85% of PV (solar) cells from China.

Thus far, the European Climate Policy has been a failure, and the consequences will be severe for the continent — and beyond. Climate policies have failed to have a tangible impact on climate change, and have proven to be a very dangerous experiment when it comes to energy security.

The sweet spot

In 2014, I joined the power and gas industry, which turned out to be a key step in the journey toward answering that initial question that haunts me; why we continue to collectively fail so badly at saving the planet. I chose to stack my experience in energy systems on top of my sustainability and climate change background and macro-economy knowledge. In my view, the intersections of those 3 expertises gives a special perspective into the world, which I call the sweet spot.

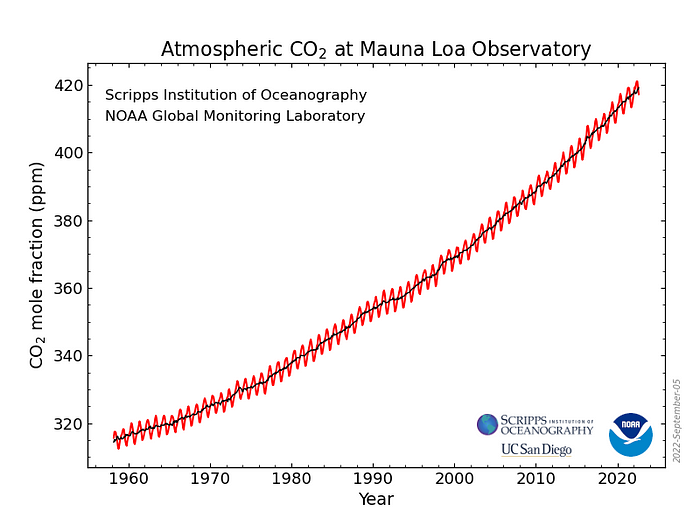

The world has tried various climate strategies for decades; they aren’t working. Still, we continue in the same direction, and we lament ourselves every year — every month — every natural disaster. The CO2 concentration continues to increase with no relief in sight.

The healthiest behavior would be to recognize the global failure, and propose an entirely new strategy. To be frank, it often feels as though some governments favor control, coercion to offset inefficient policies. Around the world, Green political parties offer ideas which would make Karl Marx turn in his grave. QR codes, carbon passes, meat banned in favor of insects (not yet, but it can feel like we’re heading in that direction). In a general trend since Covid, democracies are leaning toward authoritarianism.

Central planers are now clearly in control, and power grabs are justified in the name of the urgency of the climate crisis or else. I think it is time to be very careful with the path we choose. Wake up, or comply.

So instead of compliance, control and coercion, I explore a 180 degree turn to protect both the climate and our freedom: Let’s try to fix the incentive structure first.

Call for Change of Strategy: Change the Incentive

Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome” Charlie Munger, Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway (the conglomerate controlled by Warren Buffett).

Personally, when I am not manipulating kWh, kW, and Joules at work, or spending quality time with my family, I generally feed my interest in the macro-economy subject through podcasts and books. That hobby became much more than a hobby when COVID-19 hit in 2020; then, it almost became a second job. During commutes to work, late at night when everyone was asleep; I was curating and listening to podcasts, day-in and day-out. Thousands of hours. My favorite being the Investor Podcast from , I have learnt so much through his interviews, I am grateful for it.

The “Banana-Moment”

Sometimes you just need a little spark to move forward. My spark arrived one day on my commute home from work, in the first minutes of a 4 hour long interview by Lex Friedman, during which economist presented a metaphor that struck me.

Ammous refers to the coincidence of wants, through which society is naturally pushed to select a certain medium of exchange to trade goods. The coincidence of wants can be described by the following example, where Farmer A produces oranges but wants apples, and Farmer B produces apples but does not want oranges. If Farmer B wants bananas, then Farmer A needs to find bananas to be able to swap oranges for apples. In that case, bananas are the medium of exchange.

In the absurd, let’s imagine a social organization where bananas are the medium of exchange. Beyond the obvious problem that bananas aren’t very difficult to produce, bananas rot within days. The incentive is to get rid of the bananas as fast as possible for something more durable. You can eat the banana of course, but if you have no specific need, you will have little time to think of one. You decide to trade the soon-to-be-rotten banana for fresh wood from the forest. Reasonable. To make this trade, you ask a hungry individual to cut down a beautiful oak tree for you. You do not need the wood now or in the future, but it’s still better to have oak planks than a rotten banana. In this absurd scenario, a perfectly healthy tree has been cut down and trimmed to planks. That’s the outcome.

You wish it will be sold for more bananas in the future when you are hungry, right? You made an investment for yourself to make your future as easy as you can. You’ve found the path of least resistance; which humans are hard-wired to do. The bottom line is, a bad medium of exchange cannot protect the purchasing power across time. Bad mediums are the worst enemy for natural resources as they force short term decisions on each individual. Fiat currencies share very similar traits with the banana-medium of exchange. They do not hold value across time so they keep people busy finding a way to pass wealth across time using natural resources.

Ripe Bananas

Let’s continue to develop the banana metaphor with with 2022’s hot topic in the economy: Inflation. In this metaphor, inflation is the speed at which your banana rots.

The US money supply (all dollars in the system) increased by almost 40% since the COVID-19 crash, through hand-out and loan programs. There was no gold involved in this process; just a few mouse clicks, and look at the results.

Logic would state that if you are able to grow bananas easily, and the total amount of bananas goes up 10x, scarce ressources are going to go up in price too, denominated in banana terms. Supply chains have also suffered significantly from COVID-19 lockdowns; predominantly in China.

In the fiat-currency world we live in, when inflation or hyperinflation hits, and you have spare cash remaining after covering your essential needs (ie, consuming the banana for energy), you have two options to protect yourself against wealth destruction:

- Invest the cash and hope to beat inflation (which is very difficult to be consistent at; and it’s time consuming). Example — You cut an oak tree in exchange for your banana.

- Spend it immediately on non-essentials, or “pleasure spending” if you will (travel, race car, …).

In both cases, the action of doing so will extract more natural resources. Nobody will let their banana go to the trash without a fight, right? The threat of imminent wealth destruction is a strong incentive, and that’s exactly what high levels of inflation push us to do.

It should be made easy to save money with banks, at a rate close to inflation. However central banks deliberately kept their reference rates very low, making it impossible for the average people to match inflation. They force people to gamble with their money to not get a haircut.

Negative real rates are weapons of mass destruction. If a bank offers you a rate of 4% to borrow money when inflation prints at 8%, your real rate is -4%. You are getting paid to get the money off the table, and support projects which would, in normal conditions, go bankrupt. You sustain activities (zombie companies) which deliver no incremental value to society to protect your wealth.

Exit the Bananas, Here Comes the Wine.

To finish the demonstration, let’s imagine that the medium of exchange gets more valuable overtime; like a good wine that gets better and more valuable with age. As this is the case, why would you drink, or exchange the bottle for other goods if it’s going to be worth more tomorrow? It is clear that the incentive structure questions the choice by default:

Do I really need this thing now, because my wine will be worth more tomorrow?

Both inflationary and deflationary money have respective advantages and disadvantages which are far larger than just the environment, so I will let the Keynesian economists fight it out with the Austrian economists on the matter. That said, when it comes to protecting the climate and environment, it is clear to me that deflationary money, and sound money, gives a much better incentive structure; especially when high inflation kicks in.

Green-Shaming no More

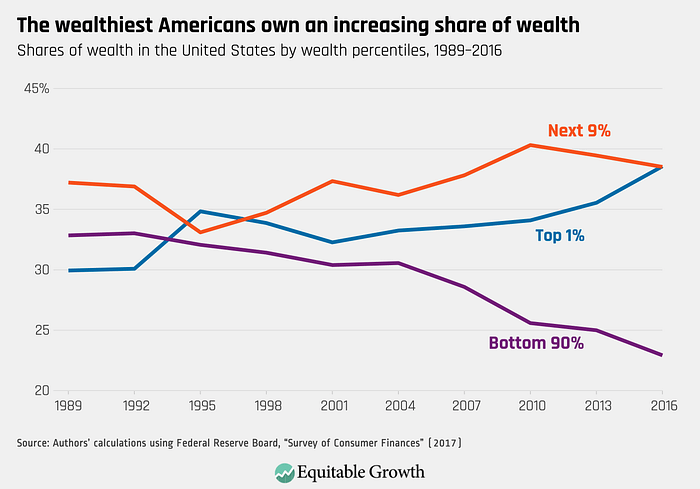

If you followed carefully until now, you might come to realize the idea that most of the impacts are generated by higher income earners trying to save their “extra bananas”. People belonging to the poorest percentiles don’t have the option to choose between investing or extra spending. Today, 90% of the population in the US own less than 23% of the wealth. 10% owns close to 77% — and the gap widens by the day.

For the poorest percentile, the incentive structure is to survive on as little money as possible. They often ride public transportation, own or rent very small residences, and manage heating very carefully. They surely don’t fly on holidays, and beef is rarely on the menu. They unfortunately don’t have any bananas to spare and thus work on their efficiency everyday.

In contrast, the wealthy people will do everything they can to protect their wealth over time. Spared bananas are invested together with borrowed bananas (leverage) in hope to generate more bananas in the future. To protect and grow wealth over time. But this goup is simply producing the outcome expected by the incentive structure, despite the impacts.

Unfortunately, most climate activists rarely make a distinction between rich and poor. In most cases, they blame the People without distinctions. People are what I call “green-shamed” without distinction. The punitive sustainability: ”You must travel less, you must eat less beef”.

But in my view, the only people to blame are those that keep the fiat incentive structure, and those who support it, in place. Not the rich, even less-so the poorest percentile of the population. It’s time to change the incentive structure instead of fighting the inevitable outcome of the fiat money. It’s time to switch to a sound money incentive if we truely care about the future of this planet.