What do you think?

Rate this book

1120 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1932

People going to be executed, people going to deathbeds, people going to bury their dead – their shadows look the same. Shadows have no hearts. Shadows are like men who have decided to follow Christ and to leave their loves and their loves’ children!

There was a feeling among them all as they went off as if they had stretched out their arms to grasp a Golden Bough and had been rewarded for their pains with a handful of dust.

“I tell you, any lie as long as a multitude of souls believes it and presses that belief to the cracking point, creates new life, while the slavery of what is called truth drags us down to death and to the dead! Lies, magic, illusion – these are names we give to the ripples on the water of our experience when the Spirit of Life blows upon it.”

What would the world be, once bereft

Of wet and of wildness? Let them be left,

O let them be left, wildness and wet;

Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.

At the striking of noon on a certain fifth of march, there occurred within a causal radius of Brandon railway-station and yet beyond the deepest pools of emptiness between the uttermost stellar systems one of those infinitesimal ripples in the creative silence of the First Cause which always occur when an exceptional stir of heightened consciousness agitates any living organism in this astronomical universe.

The nervous excitement manifested by these two was so free from traditional sentimentality and normal passion, so dominated by a certain cold-blooded and elemental lechery, that something in the fibrous interstices of the old tree against which they leaned was aroused by it and responded to it.

Thus did these two, the man from Wales and the man from Norfolk, enter the silent streets of the town of Glastonbury.The rest of the book takes place within Glastonbury and its environs. Powys introduces us to multiple characters and sub-plots and tries to show us the political, philosophical, mythological, quotidian, psychological, sexual, natural life of Glastonbury (n.b. I may have missed some). The political side of Glastonbury is demonstrated by showing three main strands of political life represented by different characters or groups of characters: there is the capitalistic, industrious group represented by Philip Crow and William Zoyland; the socialists are represented by Red Robinson and Dave Spear; and the religious/mystical represented by John Geard and Mat Dekker. There are many others, some connected to these groups, some completely separate that intertwine with this narrative within the novel but there are conflicting interests for the future of Glastonbury (Britain). Crow and Zoyland are ashamed of the mystical past of Glastonbury and want to create industry, wealth and jobs; the socialists are just as ashamed of the mysticism but want to create a commune in the town; and there is Geard, who uses his newly acquired wealth to try to revive the mystical past of Glastonbury. Geard both uses and is used by the others to attempt to accomplish their aims. For instance Geard is supported by the socialist groups to become the mayor of Glastonbury as they believe he can be used to thwart Philip Crow's industrial plans. When Geard does become mayor he decides to put on a pageant (or passion play) which ends in an amazingly chaotic mess.

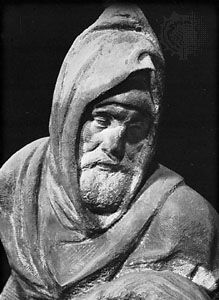

...a broad-shouldered, rather fleshy individual, without any hat, whose grizzled head under that suspended light seemed to Sam the largest human head he had ever seen. It was the head of a hydrocephalic dwarf; but in other respects its owner was not dwarfish. In other respects its owner had the normally plump, rather unpleasantly plump figure of any well-to-do-man, whose back has never been bent nor his muscles hardened by the diurnal heroism of manual labour.Geard can work a crowd, he delivers impromptu speeches to audiences, sometimes sober, sometimes drunk and sometimes under some unknown influence. He's enigmatic but shambolic. Later on in the novel he supposedly cures a cancer victim and during the opening ceremony of a Saxon Arch, he has had built, he seems to bring a recently-deceased boy back to life. Weird? Yes, meanwhile Sam Dekker, the son of the vicar of Glastonbury, has a vision where he sees the Grail in a barge on the canal. Maybe, even more strangely, Powys invests all creatures, indeed, all objects with a living spirit; but Powys has a special affection for trees; the following quote takes place whilst Owen Evans and his new wife, Cordelia, kiss in a wood next to two trees, a Scotch fir and a holly tree, which are also in love with each other.

In the summer when the wind stirs the trees, there is that rushing, swelling sound of masses of heavy foliage, a sound that drowns, in its full-blossomed, undulating, ocean-like murmur, the individual sorrows of trees. But across this leafless unfrequented field these two evergreens could lift to each other their sub-human voices and cry their ancient vegetation-cry, clear and strong; that cry which always seems to come from some underworld of Being, where tragedy is mitigated by a strange undying acceptance beyond the comprehension of the troubled hearts of men and women.But it's not all mysticism and animism, in fact, that takes up only a small part of the book; there are many affairs and other dalliances, sexual desires, repressions, sadism and murder. Owen Evans, for example, has sadistic sexual urges which he tries to purge, initially, by playing a crucified Christ at the pageant; later on in the novel he's obsessed with witnessing a murder; but in both cases he does not really have the stomach for it as his sadistic desires turn to revulsion when realised. Powys switches about between characters, human and non-human, good and evil, at one point we are viewing events from afar and then we fall into the character's mind. It can be disorienting but also exciting.

Mr. Finn Toller in his natural condition was no engaging sight. In his present state he was a revolting object. He was a sandy-haired individual with a loose, straggly, pale-coloured beard. He gave the impression of being completely devoid of both eyebrows and eyelashes, so bleached and whitish in his case were those normal appendages to the human countenance. His mouth was always open and always slobbering, but although his whole expression was furtive and dodging, his teeth were large and strong and wolfish. Mr. Toller looked, in fact, like a man weak to the verge of imbecility who had been ironically endowed with the teeth of a strong beast of prey.Finn is a nasty piece of work; he thinks that everyone is trying to inveigle him to murder people on their behalf. He's quite happy to oblige, except for women and children, so when Mad Bet does indeed urge him to murder John, whom she is besotted by, he plans an attack, which forms another sub-plot to this mesmerising novel. As with many of the local characters Finn talks, and thinks, with a Somerset accent. As a little taster of some of Powys's Somerset dialogue here are a couple of examples of Finn's:

"I never have liked these here windy nights. These here nights be turble hummy and drummy to me pore head."

"What I've got...to say, Missus, be for Mr. Robinson's ear alone. Please allow me, Missus, for all that us poor folks have got left"—he stopped and threw a very sinister leer at Red—"be what be put in our minds by they as be book-larned and glib of tongue, like this clever Mister here, who is foreman of his Worship's. Us poor dogs hasn't got anything left in the world, us hasn't, except they nice, little thoughties, they pretty thoughties, what clever ones, like Mister here, do put into we."By the way, the 'nice thoughties' are those of bludgeoning Philip Crow over the head with an iron bar. In a public speech Red Robinson had called for Philip to be 'liquidated', by which Finn takes that to mean that Robinson wants him bumped off; when he repeats Robinson's words back to him with this 'understanding' Robinson is shocked. It's gruesome but funny as well.

"A bloated capitalist, like 'im, what do hexploit us poor dawgs, ought to be lickidated." It was Mr. Toller undoubtedly who was saying that; and Red recognized his own oratorical expression, "liquidated," the meaning of which, for the word had reached him from Bristol, had always puzzled him—though this had not prevented him from using it in his orations.But AGR is not all dark, there are light passages as well, humour as well as seriousness, and realism as well as mysticism and a cataclysmic ending for good measure. The aspect I really like about his work is how the narrative weaves between all these. For example, there is a great section where Powys describes a murder and the narrative switches to that of some rooks flying above and some insects on the ground near the body, or in the earlier example where the narrative fades from Owen and Cordelia kissing to the 'thoughts' of the trees.

There is no ultimate mystery! Such a phrase is meaningless, because the reality of Being is forever changing under the primal and arbitrary will of the First Cause. The mystery of mysteries is Personality, a living Person; and there is that in Personality which is indetermined, unaccountable, changing at every second! The Hindu philosophies that dream of the One, the Eternal, as an Ultimate behind the arbitrariness of Personal Will are deluded. They are in reality—although they talk of "Spirit"—under the bondage of the idea of the body and under the bondage of the idea of physical matter as an "ultimate."

Apart from Personality, apart from Personal Will, there is no such "ultimate" as Matter, there is no such "ultimate" as Spirit. Beyond Life and beyond Death there is Personality, dominating both Life and Death to its own arbitrary and wilful purposes.

What mortals call Sex is only a manifestation in human life, and in animal and vegetable life, of a certain spasm, a certain delicious shudder, a certain orgasm of a purely psychic nature, which belongs to the Personality of the First Cause.