What do you think?

Rate this book

A brilliant, authoritative, and fascinating history of America’s most puzzling era, the years 1920 to 1933, when the U.S. Constitution was amended to restrict one of America’s favorite pastimes: drinking alcoholic beverages.

From its start, America has been awash in drink. The sailing vessel that brought John Winthrop to the shores of the New World in 1630 carried more beer than water. By the 1820s, liquor flowed so plentifully it was cheaper than tea. That Americans would ever agree to relinquish their booze was as improbable as it was astonishing.

Yet we did, and Last Call is Daniel Okrent’s dazzling explanation of why we did it, what life under Prohibition was like, and how such an unprecedented degree of government interference in the private lives of Americans changed the country forever.

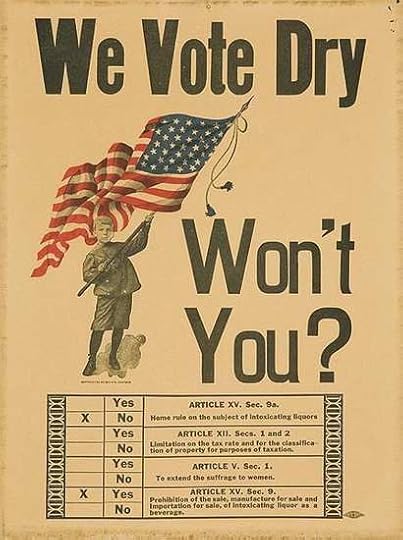

Writing with both wit and historical acuity, Okrent reveals how Prohibition marked a confluence of diverse forces: the growing political power of the women’s suffrage movement, which allied itself with the antiliquor campaign; the fear of small-town, native-stock Protestants that they were losing control of their country to the immigrants of the large cities; the anti-German sentiment stoked by World War I; and a variety of other unlikely factors, ranging from the rise of the automobile to the advent of the income tax.

Through it all, Americans kept drinking, going to remarkably creative lengths to smuggle, sell, conceal, and convivially (and sometimes fatally) imbibe their favorite intoxicants. Last Call is peopled with vivid characters of an astonishing variety: Susan B. Anthony and Billy Sunday, William Jennings Bryan and bootlegger Sam Bronfman, Pierre S. du Pont and H. L. Mencken, Meyer Lansky and the incredible—if long-forgotten—federal official Mabel Walker Willebrandt, who throughout the twenties was the most powerful woman in the country. (Perhaps most surprising of all is Okrent’s account of Joseph P. Kennedy’s legendary, and long-misunderstood, role in the liquor business.)

It’s a book rich with stories from nearly all parts of the country. Okrent’s narrative runs through smoky Manhattan speakeasies, where relations between the sexes were changed forever; California vineyards busily producing “sacramental” wine; New England fishing communities that gave up fishing for the more lucrative rum-running business; and in Washington, the halls of Congress itself, where politicians who had voted for Prohibition drank openly and without apology.

Last Call is capacious, meticulous, and thrillingly told. It stands as the most complete history of Prohibition ever written and confirms Daniel Okrent’s rank as a major American writer.

480 pages, Hardcover

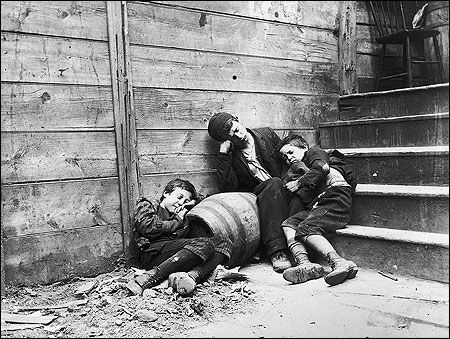

First published April 30, 2010

In almost every respect imaginable, Prohibition was a failure. It encouraged criminality and institutionalized hypocrisy. It deprived the government of revenue, stripped the gears of the political system, and imposed profound limitations on individual rights. It fostered a culture of bribery, blackmail and official corruption. It also maimed and murdered, its excesses apparent in deaths by poison, by the brutality of ill-trained, improperly supervised enforcement officers, and by unfortunate proximity to mob gun battles. One could rightfully replace our prevailing images of Prohibition—flappers kicking up their heels in nightclubs, say, or lawmen swinging axes at barrels of impounded beer—with different visions: maybe the bloated bodies of the hijacked rumrunners washing up on the beach at Martha’s Vineyard, their eyes gouged out and their hands and faces scoured by acid. Or perhaps the crippled men of Wichita, their lives devastated by the nerve-destroying chemicals suspended in a thirty-five-cent bottle of Jake. (page 371)

Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition by Daniel Okrent.

'controlled six Congresses, dictated to two Presidents . . . , directed legislation for the most important elective state and federal offices, held the balance of power in both Republican and Democratic Parties, distributed more patronage than any dozen other men, supervised a federal bureau from the outside without official authority, and was recognized by friend and foe alike as the most masterful and powerful single individual in the United States.'Living in an era alongside the likes of Fords, Rockefellers and du Ponts, that’s saying something. We still remember those titans of industry, and even another unrelenting supporter of Prohibition, William Jennings Bryan, but of Wayne Bidwell Wheeler. . . .

In almost every respect imaginable, Prohibition was a failure. It encouraged criminality and institutionalized hypocrisy. It deprived the government of revenue, stripped the gears of the political system, and imposed profound limitations on individual rights. It fostered a culture of bribery, blackmail, and official corruption. It also maimed and murdered, its excesses apparent in deaths by poison, by the brutality of ill-trained, improperly supervised enforcement officers, and by the unfortunate proximity to mob gun battles.He also noted that Prohibition did affect overall alcohol consumption, a substantial per capita reduction that lasted for several decades, so it wasn’t all for naught. But for that effect, this ordeal strikes me as a regrettable example of something that a government operating for the welfare of all should never undertake and that we, the people, should be ever vigilant against those misguided voices that would lead us down similarly harmful paths in the future.

High school attendance did not become commonplace until the 20th century. In 1910, just 14% of Americans aged 25 and older had completed high school. As recently as 1970, the high school completion rate was only 55%. In 2017, 90% of Americans aged 25 and older had a high school degree.How could Americans know what to think of Prohibition. At some point, it all became too complicated and Americans washed their hands of it all.