Volcker 2.0: Interest Rate Volatility and the Powell Put

Eric Tymoigne

Associate Professor of Economics, Lewis & Clark College

“The BTFP, however, goes too far by valuating any “qualifying assets” (read “whatever the Fed deems relevant”) at par. Yes, a lender of last resort should provide emergency funding and, yes, it should do so in a way that counter the devaluating effect of market rates that reflect a market panic; but it should also do so by accounting for the quality of the assets.

We do not want a repetition of the appalling response to the 2008 crisis when the government allowed banks to hide losses through the manipulation of accounting rules, the purchases of bad assets at par, and the provision of financing at a near zero rate against toxic assets.”

The regional and international financial instability that we have experienced recently is a stark reminder of the limits of an aggressive tightening of monetary policy. If balance sheets and debt services are sensitive to changes in interest rates, a rapid increase in the policy rate runs into a financial-stability barrier.

This point has been made many times by economists who reject the validity of the “Schwartz Hypothesis”, which states that by focusing on price stability a central bank also promotes financial stability and “will do more for financial stability than reforming deposit insurance or reregulating” (Schwartz 1988, 55). Contrary to such a hypothesis, many economists have emphasized the destabilizing effect of an aggressive monetary policy. John Maynard Keynes’s square rule, what is now known as the “liquidity trap”, noted the duration risk involved in aggressive monetary policy. Hyman P. Minsky from the 1960s argued that active monetary policy must be conditional on the state of fragility of the financial system (e.g., Minsky 1964, 1972, 1975). Nicholas Kaldor concluded that “there must clearly be limits to the freedom of the central bank to use the interest weapon if the solvency and viability of financial institutions is to be preserved” (Kaldor 1982, 13). The point was further emphasized and developed by post-Keynesians and generated a vigorous debate among proponents of the Inflation Targeting framework (Tymoigne 2009a, 2009b).

Monetary policy over the past year: The return on interest rate volatility

As inflation persisted and accelerated through 2021, the Fed concluded that it had misjudged the transitory aspect of inflation and decided to radically change course. A Senate hearing on March 3, 2022 gave a taste of what was to come:

SENATOR SHELBY. [Volcker] brought the leaderships of the Fed into the country that we had to squeeze inflation out at all costs. And a lot of it was draconian, you have to do it. Is the leadership of the fed under you and the Fed prepared to do what it takes to get inflation under control and protects price stability?

CHAIRMAN POWELL. […] I hope that history will record that the answer to your question is yes.

SENATOR SHELBY. You are prepared to do whatever it takes without any reservation to protect price stability?

CHAIRMAN POWELL. Yes.

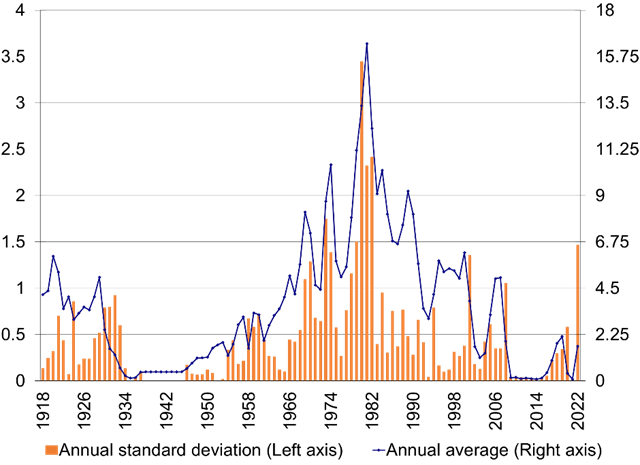

Senator Shelby was referring to the Volcker experiment of the late 1970s/early 1980s. The experiment led to very rapid increases in the federal funds rate (FFR) that wrecked the economy and the financial system. The experiment is, wrongly, credited with restoring price stability. Following that March hearing, the Fed increased its FFR target in a very rapid fashion. While the FFR level is still far from Volcker’s time, its volatility reached level similar to 1979 (Figure 1). Only in four others years — 1973, 1980, 1981 and 1982 — was the FFR volatility significantly higher.

Impact on the banking system

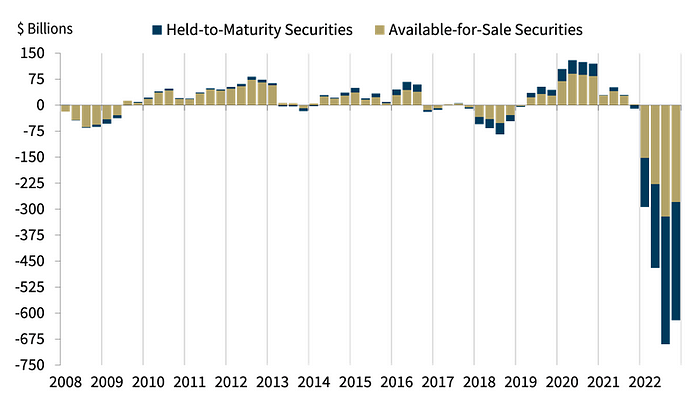

For a financial system accustomed to gradualism, the response of the Fed was quite a shock. The rapid increase in interest rates has had a severe impact on the balance sheet of banks loaded with securities sensitive to such changes in interest rates. Unrealized losses on securities accumulated quickly to reach about over $600 billion at the end of the year (Figure 2). These unrealized losses were especially detrimental to community banks that “continued to report a higher proportion of assets with maturities longer than three years at 54.7 percent of total assets.” Further losses, north of $1 trillion, can be expected due to rising default and fall in asset value, especially so if the Fed continues on its course of actions.

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) (followed by Signature Bank) was the first casualty of the new monetary policy strategy. This was due to the specific nature of the deposits it issued, its inappropriate response to the Fed policy decisions and deregulatory policies and lax supervision that encouraged lax liquidity management of regional banks. First, following the rapid rise in interest rates, SVB decided not to report significant losses on its securities by moving them to the Held-to-Maturity (HTM) category. An important implication of such a move is that SVB did not hedge against the potential realization of losses on such securities because it was supposed to hold them until they pay parity. However, such payment would not have occurred for many years. Second, while it did not hedge against such unrealized losses, it also did not build enough of a liquidity buffer given its unrealized losses on its securities and given the unusually large proportion of deposits with a nominal value far in excess of the $250,000 FDIC insurance limit. Third, rapid outflows on such deposits began when account holders had to make payments and then moved funds to earn higher interest rates. In order to meet the interbank payments that resulted from the outflows, SVB had to sell HTM securities and so had to recognize losses on them. This put a significant dent on its liquidity and net worth, which ultimately led to a run on SVB by depositors who fear that they would not recover their funds.

The response of the Fed: The Powell Put

In order prevent a general panic over the solvency of regional banks, FDIC took over the two regional banks and lifted the deposit insurance limit on the deposits they issued, while the Fed has provided emergency credit lines via the traditional Discount Window (that has recorded a record level demand for credit) and the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP). Overall, this was the right response. By funding banks at stable and low discount rate, the BTFP has prevented the forced sale of securities that lost value because of the aggressive Fed policy. By lifting the deposit insurance limit for SVB and Signature Bank account holders, the FDIC has protected the payment system and avoided further panic among regional banks. Unfortunately, Yellen’s testimony on March 16 resumed the fear that depositors at regional banks should not expect the same level of protection as depositors at large banks, which regenerated instability.

The BTFP, however, goes too far by valuating any “qualifying assets” (read “whatever the Fed deems relevant”) at par. Yes, a lender of last resort should provide emergency funding and, yes, it should do so in a way that counter the devaluating effect of market rates that reflect a market panic; but it should also do so by accounting for the quality of the assets. We do not want a repetition of the appalling response to the 2008 crisis when the government allowed banks to hide losses through the manipulation of accounting rules, the purchases of bad assets at par, and the provision of financing at a near zero rate against toxic assets. The provision of reserves through the Discount Window should only be for illiquid banks, not insolvent banks. Pricing any “qualifying assets” are par is a potential slippery slope away from a carefully analysis of such solvency.

If the crisis ever generalized, the proper response it to declare a bank holiday, send an army of supervisors to analyze the books of banks, and only allow the banks that are judged solvent to reopen. Those that are insolvent should be resolved in a smooth fashion through well-established government resolution channels. The Prompt Corrective Action framework mandates that government acts this way for all FDIC-insured banks. We have plenty of historical evidence that such a response is not only feasible, but also the correct response. This should occur regardless of the size of the bank; no bank is too big to fail. By taking over and resolving in a smooth fashion insolvent banks, while at the same time protecting the payment system through an unlimited guarantee of deposits, the government stabilizes the financial system while promoting a return to prudent banking practices.

Financial Stability is the Primary Concern of the Fed

The abrupt change in monetary policy course over the past year is also a reminder that for private banking to work smoothly, there must be a stable refinancing source. This is not an issue of “financial dominance,” it is what the purpose of the Fed is. The Federal Reserve was created to provide such reliable source and to regulate banks, it was not created to manage economic activity and price stability. Active involvement in such endeavor, especially in period of high price instability, cannot occur without providing major financial backstops to the financial sector. The Powell Put is the last iteration of such backstop and if Powell decides to do “whatever it takes” to tame inflation one can expect much further government support.

In 1972, Minsky concluded presciently that:

A conditional cash flow analysis of individual, and classes of, financial institutions will estimate the impact of various alternative policy and market-determined conditions upon the individual institutions and the set of institutions. For example, there may be a limit to tight money — due to the running losses, as illustrate earlier — that a nonblank financial intermediary, such as the savings and loan associations, can stand. The Federal Reserve must look beyond the commercial banking system to determine whether, or in what circumstances, its actions are destabilizing.

This ought to be a point of departure for monetary policy decisions. And stress tests are a poor tool to do that as the Counterparty Risk Management Policy Group noted long ago. In an age of secular stagnation, a central bank has limited leeway to raise rates, all the more so aggressively. A proper central bank policy would leave rates low and stable for many years to come and let inflation be managed in other ways (Tymoigne 2021).

An additional point that Minsky brought forward is that the Discount Window should be the normal means to provide a reliable refinancing source for financial institutions. Through this channel, the Fed has a much better sense of the activities in which financial institutions are involved and can influence their financial practices through its collateral management practices. Such practices involve setting the discount rate on such collateral and accepting or refusing such collateral. This should be one leg of a regulatory framework that acts proactively (instead of merely reactively through capital and liquidity buffer) to promote “hedge finance.”