If I were a teenager and sat down to dinner with people who turned out to be former nazis, I wouldn’t just let that fact slide, oh no!

I’d punch them! Or at the very least, I’d tell them that nazis are bad. That’s what I’d do. I’d definitely not sit there eating and be perplexed about having dinner with these people (as the child of two Holocaust survivors). Not just any kind of nazi, former Waffen SS. So perplexed, in fact, I would often think back of the event, decades later.

Thus many people who are not children of holocaust survivors declared confidently on Twitter what they would do. It seems ages ago but really, it was less than two months ago, when Jason Stanley, a professor of philosophy, said that this exact scenario had happened to him.

I think we missed out on a lot of interesting nuanced discussion on post-world war II Germany (and Europe generally) having to somehow integrate its offenders back into society. How Europe in the decades following the war had to a way to live with its past where lots of ordinary citizens were complicit in the most heinous transgressions.

The cheerful “punch the nazis” doesn’t offer us anything concrete on how to deal with fascists and nazis, or what we can do to stymie the tide of widespread sympathies for their policies in contemporary nation states. People we know who vote for the far right are our neighbors, family members, colleagues. What to do?

We find ourselves in morally complex situations all the time, where we are faced with difficult and suboptimal decisions, as recent events came out regarding the whisper network (the informal channel where people are warned, usually by more seasoned members of the profession, about problematic behaviors of often prominent fellow members.)

So (I apologize for reiterating some speaking of ill of the dead soon after their demise, but since there is again widespread discourse I hope it is OK), when news of Saul Kripke’s death broke out, everyone was suddenly talking about how problematic he was. I had no idea, literally–I had never met him, and somehow, that part of the whisper network never reached me. Because the whisper network is cliquish it is not surprising in a sense to see people those past few days say “I knew it all along, this was widespread, everyone knew” and “this is the first I hear about it”. Whisper networks are suboptimal substitutes for justice. They are opaque, they require acquaintance with the right circles to know (and face-to-face conversations), they can, of course, sometimes go wrong.

What do we do with the moral murkiness of the situations we find ourselves in? I was recently thinking about this with respect to admiring work of people who turn out to be deeply problematic (this loosely follows an earlier Twitter thread I wrote on this, see there for more thoughts).

In our desire for moral clarity, we will say things such as “As soon as I learned about his harassment I took him out of the syllabus!” or “I disliked her work before it was cool to dislike it.”

And that’s fine, of course. But we have to reckon with how ubiquitous this moral murkiness is. You can say “I never liked JK Rowling, Joss Whedon, Woody Allen” (even before their problematic behavior came to the fore) but, lacking a moral crystal ball, at some point, you’ll likely find someone you admired is problematic.

This can be a true gut punch. We can feel betrayed, in a sense, even if we never knew the person. For instance, I enjoyed Marion Zimmer Bradley’s speculative Arthurian stories in Mists of Avalon and felt gutted when I heard she was an abuser. Precisely because the stories have a feminist lens to interpret Arthur and Morgan le Fay, I was shocked to learn that she abused a girl.

It would be easy if we could always say about problematic people that their art, or other creative work sucks. Much like the fox in Aesop’s fable declares “the grapes are too sour anyway”, we declare “this work was really never any good anyway.”

But I don’t think we can do this so easily. Take Joss Whedon, I can see why some people say “Oh Buffy was never that good, or that feminist to begin with” when his bullying behavior toward actors (such as fat-shaming a pregnant actor) was revealed. But perhaps more disturbing is that Buffy is feminist and powerful, and that somehow, Whedon failed to live in accordance with the feminist message of his stories.

If he couldn’t, then how could we? How can we feel confident in the projects or goodness we saw in Whedon’s (and other people’s) work and how it affected us? Was it all a lie, or shallow? We feel that sense of betrayal in part because we as audience aren’t passive recipients. It is the beauty of art and any creative endeavor of course, that we as audience, co-create the work. But that also calls for responsibility, for asking hard questions about being made complicit in some of the bad effects of those people’s works and their actions.

I think this is in part what lies at the heart of liking/admiring the work of problematic people. Not so much the question of whether we can separate a creator from their creations but the role we play, as audience. How to sit with the ambiguity of “X was a brilliant philosopher” and “X was a serial harasser.” There is no easy moral clarity.

This is not only so for living and recently deceased authors, but also more distant ones. For instance, the fact that Kant died over two centuries ago doesn’t make his racism OK. And before people say “man of his time” there were plenty of non-racist and anti-racist philosophers at the time. Kant used his platform for ill, and his endorsement of racist anthropology and pseudoscience has as an effect that non-western philosophy is pushed out of western philosophy departments to this day, as Peter Park details in this excellent book. If anything, a long-dead author has a longer ripple effect of potential bad effects of their views. So, it is right for Hume scholars to ask themselves hard questions about the Hume statue in light of his racist views. Tearing down statues is not the end of this debate or the only moral course of action.

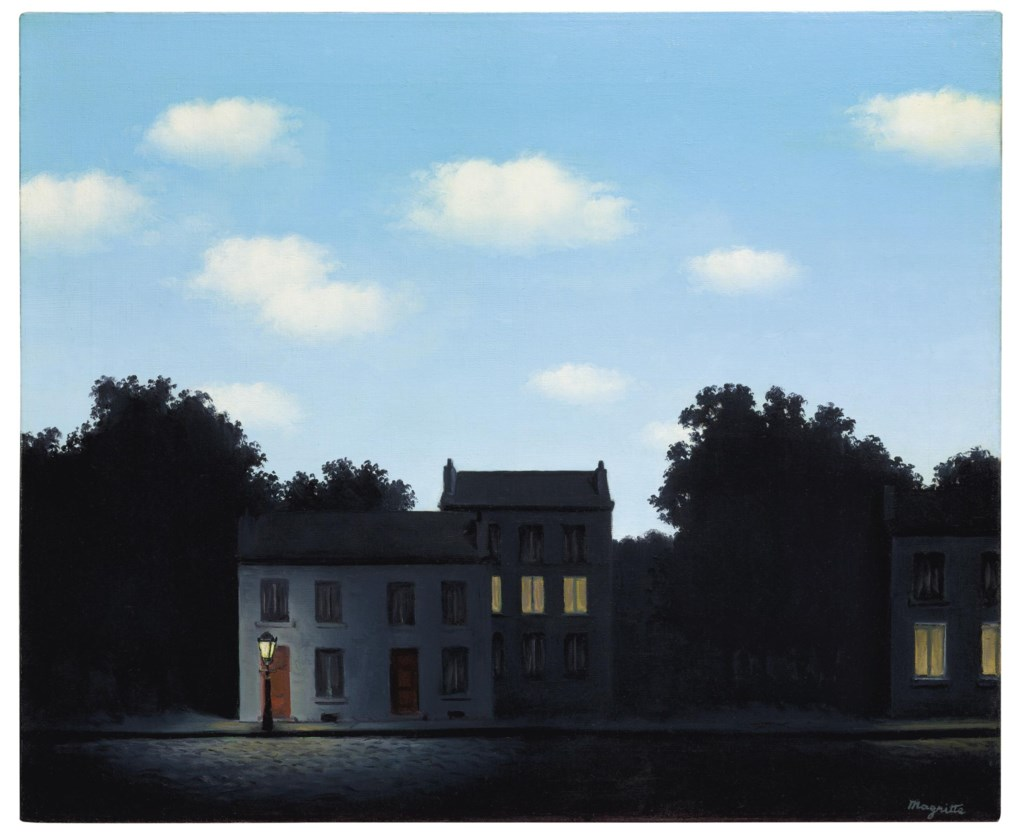

I am recently enjoying movies by Jean-Pierre Melville, and one of the things I think sublime in his work is how he manages to help us think about the light and the dark. In his Army of Shadows (1969) Melville portrays French resistance fighters in World War II. The people we’d all say (if the discourse in response to Stanley is to be believed) we’d be if we lived in World War II. Melville was Jewish and a resistance fighter. What he shows in the movie is the tremendous moral ambiguity of being a resistance fighter, the sense of being watched, the fear of being sold out by your allies, the hard decision of having to kill someone who is compromised in your group, no matter how wonderful this person is. In this way, Melville shows us the dark within the light. Even being as right as one can possibly be, a resistance fighter in World War II, is not a Manichean situation of good against evil where we find moral clarity. Then again, Melville also shows us light in the dark in a movie such as Le Samourai (reviewed here) where you can find self-sacrifice and a deontological adherence to duty in a hired killer.

Great artworks like these can help us to think more about the relationship between light and dark, not the polar opposites of a manichean world, but a murky, messy situation where we find ourselves making suboptimal decisions in an imperfect world. We’re often made complicit, much as in the dinner with nazis, or enjoying the comfort of reading a work by a very problematic author, we deal with the light in the dark, and the dark in the light.

Good stuff but I object to JK Rowling being listed among people who “morally problematic”. It seems it has become ok to say this casually when if you actually look at all she has ever said, you may disagree with a great deal, but nothing is egregiously wrong. Lumping her with Joss Whedon and Woody Allen is, I’d say, morally problematic.

LikeLike

I don’t think so–I think there is enough evidence, for instance with her recent book, and her anti-trans activism, to say that at least some people find her problematic (note you also still have defenders of Woody Allen etc). But the points I make don’t require a universal opinion, just about what to do (as many people do) who still love the Potter books but strongly object to Rowling’s anti-trans activism.

LikeLike