What do you think?

Rate this book

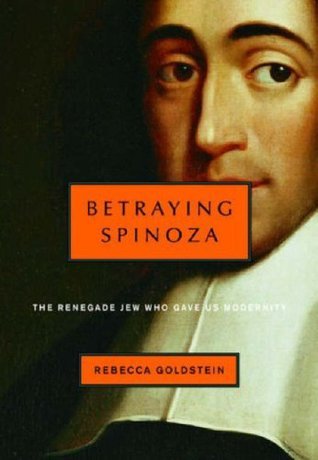

287 pages, Hardcover

First published May 30, 2006

If the way which I have pointed out, as leading to this result, seems exceedingly hard, it may nevertheless be discovered. Needs must it be hard, since it is seldom found. How would it be possible, if salvation were ready to our hand, and could without great labor be found, that it should be by almost all men be neglected? But all things excellent are as difficult as they are rare.

From causa sui to salvation. Salvation is achieved by bringing the vision of the causa sui--the vast and infinite system of logical entailments of which each of us is but one entailment--into one's very own conception of oneself, and, with that vision, reconstituting oneself, henceforward living, as it were, outside of oneself. The point, for Spinoza, is not to become insiders, but rather outsiders. The point is to become ultimate outsiders.

The word "ecstasy" derives from the Greek for "to stand outside of." To stand outside of what? Of oneself. It is in that original sense that Spinoza offers us something new under the sun: ecstatic rationalism. He makes of the faculty of reason, as it was identified through Cartesianism, a means of our salvation. The preoccupations of his inquisitorially oppressed community come together with the mathematical inspiration of Cartesianism to give us the system of Spinoza.

Only Spinoza had to fight his way clear of the dilemmas of Jewish being, fighting all the way to ecstasy. ...

Spinoza names the ecstasy his system delivers amor dei intellectualis, the intellectual love of God.